- Ceramic patterns and color glazes on ultra-high temperature ceramics providing analytical insights into thermal compatibility

Changbing Lia, Binrong Huangb and Shouliang Laib,*

aKangwon National University, Chuncheon City, 200701, Gangwon Province, South Korea

bHunan University of Technology, 412000, Zhuzhou, Hunan, ChinaThis article is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

The combination of aesthetic and functional features in ceramics opens new possibilities for both cultural and engineering applications. This study examines the interaction among patterned surfaces, color glazes, and ultra-high temperature ceramics (UHTCs) through an analytical and data-driven methodology. Substrate parameters for UHTCs were obtained from the literature, and high-temperature stable glaze properties were compiled from open-access glaze datasets. Thermal mismatch stresses between the glaze and substrate were determined using an analytical thin-film model, and steady-state temperature gradients across the glaze, UHTC bilayer were evaluated under high-temperature conditions. The influence of pattern geometry on local stress distribution and glaze thickness variation was discussed qualitatively. The results demonstrate how glaze composition, colorants, and firing conditions affect both aesthetic stability and structural resilience at extreme temperatures. This framework facilitates the design of UHTCs that combine visual appeal with oxidation resistance, offering potential applications in architectural surfaces, high-value decorative artifacts, and aerospace components.

Keywords: Aesthetic stability, Ceramic patterns, Ultra High Temperature Ceramics, Color glaze.

Historically, ceramics have been valued for their beauty as well as their usefulness. They have been used as both useful objects and works of art in many cultures [1]. Traditional uses of ceramics have been to make decorative patterns, intricate textures, and color glazes that make things look better and protect the surface [2]. Modern engineering ceramics, on the other hand, are made to stand up to very high temperatures, very high pressures, and very harsh chemicals. Examples include zirconium diboride, hafnium diboride, and silicon carbide based composites. These materials are very hard, have high melting points, are very stable at high temperatures, and are very resistant to oxidation and corrosion [3]. This makes them necessary for demanding uses like aerospace thermal protection systems, high-temperature industrial processes, hypersonic vehicles, and advanced energy generation components. UHTCs are a very important type of material because they can perform well in extreme conditions and can be used for surface engineering. They bridge the gap between structural functionality and advanced surface design [4].

Even with the notable progress in UHTC development, there is still much to learn about how to combine exceptional functional performance with visual appeal [5]. The structural and color stability of traditional ceramic glazes and patterned surfaces under the ultra-high temperatures associated with UHTCs is uncertain because they are usually designed for conventional firing temperatures, which are typically below 1300 oC [6]. Glaze layers and UHTC substrates have different thermal expansion coefficients, which can result in significant thermal stresses during heating and cooling cycles. These stresses may cause cracking, spallation, delamination, or deterioration of surface patterns and color. These difficulties show that evaluating decorative glazes suitability for high-performance ceramic substrates requires a methodical approach [7]. Understanding how surface patterning, firing conditions, and glaze composition affect structural integrity and aesthetic stability enables the design of UHTC-based ceramics that satisfy the demanding mechanical and thermal requirements of extreme applications without sacrificing aesthetic appeal.

The increasing availability of open-access glaze datasets and established analytical modeling approaches provides a practical framework for evaluating the performance of glazes on UHTC substrates without extensive laboratory experimentation. The thermal mismatch stresses that result from variations in the glaze and coefficients of thermal expansion of the substrate can be predicted using thin-film stress models, and the temperature distribution throughout the bilayer system during high-temperature exposure can be understood using steady-state thermal gradient calculations. Qualitative evaluations of surface pattern geometry can also reveal possible differences in glaze thickness and local stress distribution, providing direction for maximizing both structural durability and aesthetic consistency. The combined effects of glaze composition, colorants, firing conditions, and pattern design on the look and functionality of UHTC-based ceramics can be methodically examined by combining these data-driven analyses.

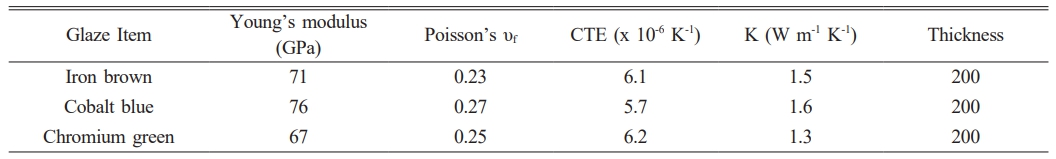

UHTC were chosen as the substrate materials Because of their great oxidation resistance, hardness, and thermal stability. Zirconium diboride, hafnium diboride, and composites based on silicon carbide (SiC) are the main materials taken into consideration. To ensure accurate representation of extreme-temperature behavior, the following substrate properties were gathered from literature sources: thickness, Poisson’s ratio, Young’s modulus, coefficient of thermal expansion (CTE), and thermal conductivity. The Glazy repository, which offers oxide-based formulations, firing temperatures, and visual color results, is one of the open-access databases from which glaze compositions were chosen. The selection of glazes was based on their ability to withstand high temperatures and their potential for decorative use on UHTC surfaces. Young's modulus, Poisson's ratio, CTE, thermal conductivity, thickness, firing temperature, and dominant colorant oxides are important parameters that are gathered for every glaze.

Thermal stresses induced in the glaze layer due to differential thermal expansion between the glaze and substrate were calculated using a thin-film analytical model. The glaze was treated as a thin layer bonded to a thick substrate, and the mismatch stress σf, was determined using the relation:

Ef and υf are the Young’s modulus and Poisson’s ratio of the glaze, αf and αs are the coefficients of thermal expansion for the glaze and substrate, ∆T = Tmax - Tmin is the temperature difference between peak firing or service temperature and reference temperature.

Steady-state thermal gradients across the glaze-UHTC bilayer were calculated to assess potential temperature differences between layers, which influence stress development and color stability. The temperature drop across each layer was estimated using:

where:

q is the applied heat flux, t is the layer thickness, and k is the thermal conductivity of the layer.

This calculation provides insight into how glaze thickness, thermal conductivity, and substrate properties affect the thermal environment experienced by the glaze during firing or high-temperature service.

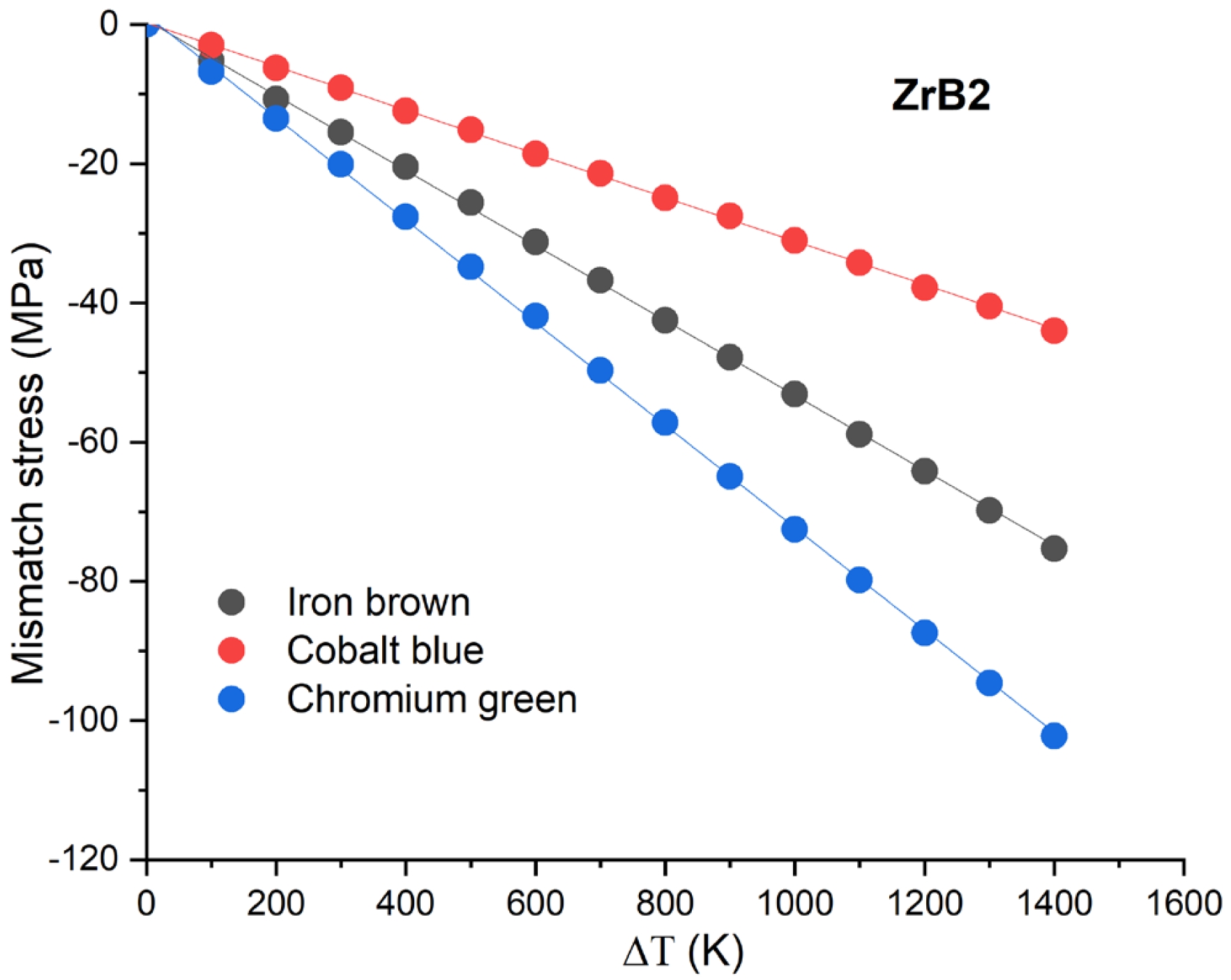

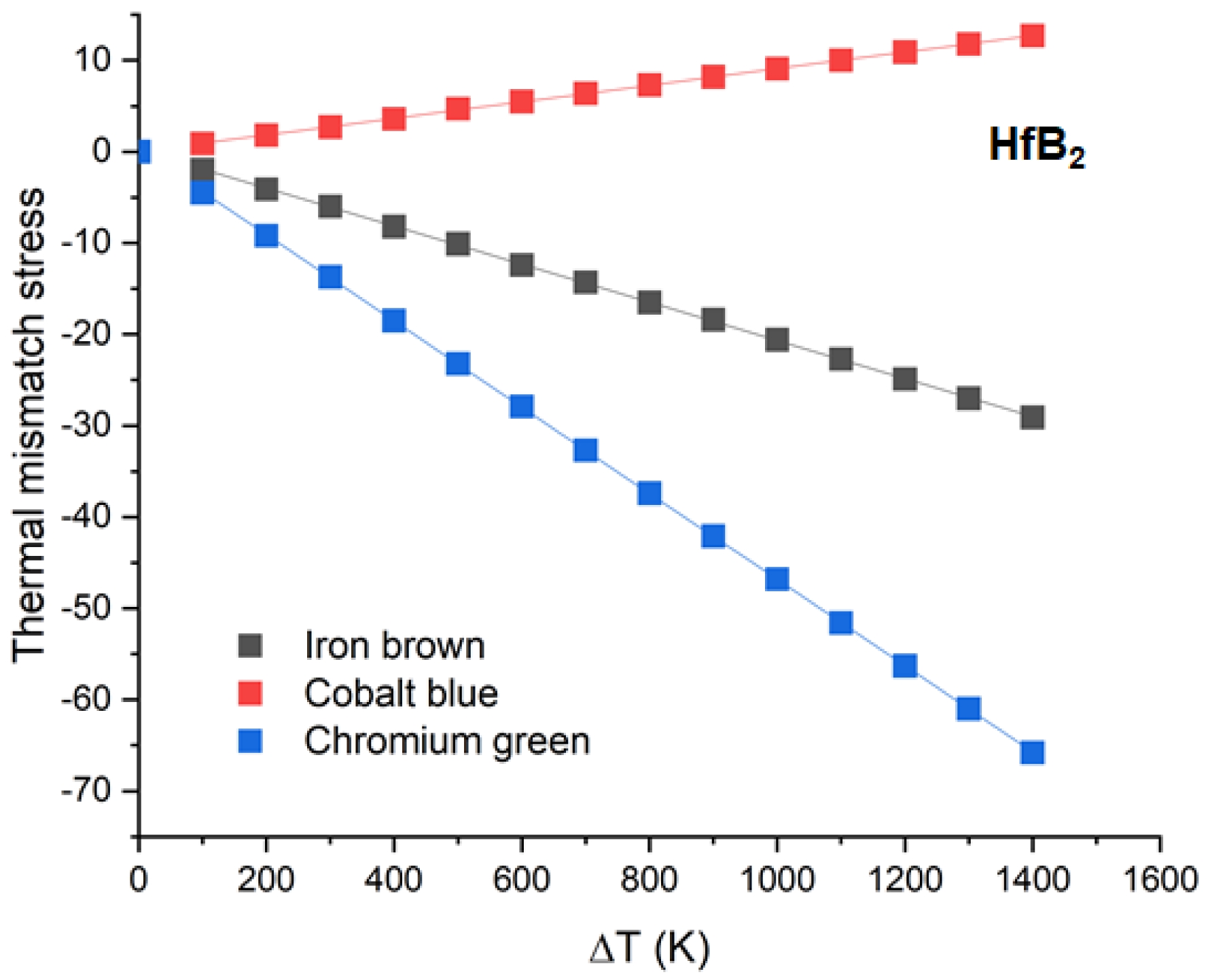

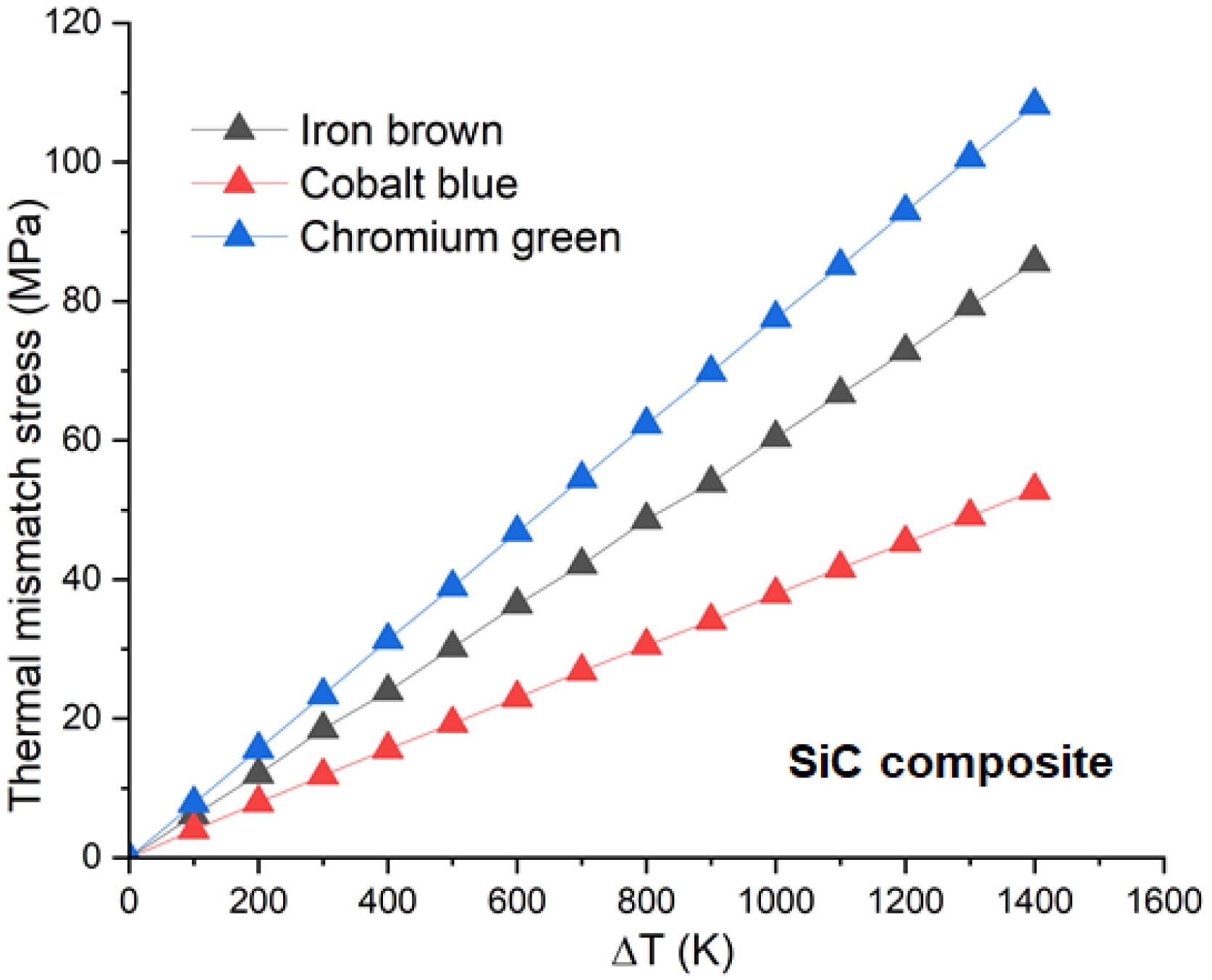

The calculated thermal mismatch stresses for the three representative glazes (iron-brown, cobalt-blue, and chromium-green) on different UHTC substrates (ZrB₂, HfB₂, and SiC composites) are presented as a function of temperature difference (ΔT). In all cases, stress increased nearly linearly with ΔT, confirming the validity of the thin-film analytical model used in this study. The slope of each stress–ΔT curve reflects the combined influence of glaze elastic modulus, Poisson’s ratio, and the CTE mismatch relative to the substrate, which together dictate the mechanical compatibility of the bilayer system [8].

For ZrB₂ substrates (αs ≈ 5.5 × 10⁻⁶ K⁻¹), all glazes developed mismatch stresses, with values ranging from approximately −36 MPa (cobalt-blue) to −64 MPa (chromium-green) at ΔT = 1200 K (Fig. 1). This behavior arises because the CTEs of the tested glazes exceed that of the ZrB₂ substrate, causing the glaze to contract more strongly during cooling. From a structural perspective, compressive stresses within the glaze are advantageous, as they inhibit surface crack initiation and slow down crack propagation. However, excessive compressive stress, particularly above ~60 MPa, may promote out-of-plane buckling or spallation of the glaze layer if adhesion to the substrate is insufficient [9]. The chromium-green glaze, while visually attractive and stable in coloration, represents a critical case where design optimization of thickness or firing protocol would be necessary.

For HfB₂ substrates (αs ≈ 6.5 × 10⁻⁶ K⁻¹), the stress magnitudes were systematically lower, with values of approximately −28 MPa (cobalt-blue) to −51 MPa (chromium-green) at ΔT = 1200 K (Fig. 2). The reduced stress arises from the smaller mismatch between substrate and glaze CTEs. This suggests that HfB₂ substrates provide a more mechanically compatible platform for decorative glazes, reducing the risk of delamination while maintaining high oxidation resistance. Importantly, the iron-brown glaze maintained stress levels below −40 MPa across the entire ΔT range, indicating that such a combination could balance aesthetic durability with structural reliability, making it a promising candidate for architectural UHTC applications [10].

In contrast, SiC-based composites (αs ≈ 4.0 × 10⁻⁶ K⁻¹) displayed the most severe mismatch stresses. At ΔT = 1200 K, cobalt-blue glaze reached stresses of nearly −52 MPa, while chromium-green exceeded −80 MPa. The significantly higher mismatch stems from the much lower substrate CTE, which amplifies contraction differentials during cooling. While compressive stresses again aid in crack resistance, values exceeding −70 MPa are well within the range that can initiate micro-buckling or interfacial debonding under thermal cycling. This result highlights that not all UHTC–glaze combinations are equally viable, and substrate–glaze pairing must be carefully chosen to avoid catastrophic mechanical failure during service [11].

The role of glaze composition is also noteworthy. Chromium-based glazes, while imparting vivid green coloration and good oxidation resistance, consistently produced the highest stresses across all substrates, suggesting a trade-off between optical performance and mechanical stability. Cobalt-blue glazes, conversely, yielded the lowest stress levels, indicating greater compatibility with UHTCs, albeit with potential risks of cobalt volatilization at very high temperatures. Iron-brown glazes provided intermediate stress values, balancing both aesthetic stability and mechanical compatibility.

Additionally, scatter plots with linear regression fitting of σf against ΔT revealed coefficients of determination (R²) above 0.99 for all glaze–substrate pairs, confirming the near-ideal linear dependence predicted by the analytical model. From the slope of these fitted lines, effective glaze substrate CTE mismatches were back calculated, providing a quantitative design parameter for predicting glaze performance under arbitrary firing or service conditions [12].

Taken together, these results underline the dual role of decorative glazes on UHTCs: (i) as aesthetic modifiers that enhance cultural and architectural acceptance of high-performance ceramics, and (ii) as mechanical modifiers whose compatibility with substrates dictates long-term structural reliability [13]. Optimizing glaze thickness, firing temperature, and compositional tuning of colorants emerges as a viable pathway to achieve both beauty and durability in next-generation ceramic systems designed for extreme environments. The differences among the three glaze compositions were evident across all substrates. The chromium-green glaze consistently exhibited the highest mismatch stress magnitude due to its higher CTE and moderate elastic modulus, making it prone to either compressive spallation (on ZrB₂) or tensile cracking (on SiC composites) [14]. Iron-brown glaze displayed intermediate mismatch values, while cobalt-blue glaze showed the most favorable compatibility, particularly with HfB₂, where stresses approached zero. This suggests that cobalt-based colorants yield glaze formulations with CTEs more closely aligned to UHTCs, potentially offering both visual stability and mechanical reliability. By adding patterned geometries, localized stress concentrations, and uneven glaze thickness that occur in real-world applications, computational modeling, in particular, finite element analysis, or FEA, could expand the current framework. Additional recommendations for maximizing mechanical and aesthetic performance may be provided by parametric studies of different glaze thicknesses, firing profiles, and multilayer glaze designs.

More thermal stability while maintaining visual vibrancy may also be possible with the investigation of new glaze compositions designed to work with UHTCs, such as colorants based on rare earth oxide or nanostructured pigments [15]. Given the intended uses in architectural and aerospace contexts, a systematic investigation into the environmental stability of these systems under oxidative and corrosive conditions is also necessary. In the end, developing UHTCs that blend durability and beauty in harsh environments will be accelerated by bridging aesthetic and functional design through integrated experimental, analytical, and computational approaches. Fig. 3 Table 1

|

Fig. 1 Thermal mismatch stress vs. ΔT for iron-brown, cobaltblue, and chromium-green glazes applied on ZrB₂ substrate. |

|

Fig. 2 Thermal mismatch stress vs. ΔT for iron-brown, cobaltblue, and chromium-green glazes applied on HfB₂ substrate. |

|

Fig. 3 Thermal mismatch stress vs. ΔT for iron-brown, cobaltblue, and chromium-green glazes applied on SiC composite substrate. |

Through the analytical assessment of thermal mismatch stresses, this study investigated the interaction between patterned ceramic glazes and UHTC substrates. The results showed a nearly linear dependence of mismatch stress on temperature difference (ΔT) using representative glaze compositions: iron-brown, cobalt-blue, and chromium-green applied to ZrB₂, HfB₂, and SiC-based substrates. Poisson's ratio, the glaze elastic modulus, and the thermal expansion mismatch with respect to the substrate all influenced the slope of this stress-temperature relationship.

Because HfB₂ is more compatible with glazes in terms of thermal expansion, it showed the lowest mismatch stresses among the substrates under study, indicating better long-term stability in decorative applications. Concerns regarding spallation and interfacial debonding under thermal cycling were raised by the fact that SiC-based composites produced the most severe compressive stresses, while ZrB₂ displayed moderate stress levels. Another important factor was the glaze compositions themselves: iron-brown produced an intermediate balance between mechanical compatibility and aesthetics, cobalt-blue the lowest, and chromium-green the highest stresses.

- 1. E.V. Clougherty, E.T. Peters, and D. Kalish, in (ManLabs, Inc., Cambridge, Mass., 1969)

- 2. W. Tripp and H. Graham, J. Electrochem. Soc. 118[7](1971) 1195.

-

- 3. W.S. Williams, Prog. Solid State Chem. 6(1971) 57-118.

-

- 4. J. Sekhar, J. Liu, and V. de Nora, Metallurgical and Materials Transactions B 29[1] (1998) 59-67.

-

- 5. H. Zhang and F. Li, J. Sol-Gel Sci. Technol. 45[2] (2008) 205-211.

-

- 6. G. Kaptay, G. Csicsovszki, and M.S. Yaghmaee, in An absolute scale for the cohesion energy of pure metals2002 (Trans Tech Publ, 2002) p. 235-240.

-

- 7. S.K. Mishra and L.C. Pathak, Key Eng. Mater. 395 (2009) 15-38.

-

- 8. B. Yang, J. Li, B. Zhao, Y. Hu, T. Wang, D. Sun, R. Li, S. Yin, Z. Feng and Q. Tang, Powder Technol. 256 (2014) 522-528.

-

- 9. Q.-J. Hong and A. Van De Walle, Phys. Rev. B 92[2] (2015) 020104.

-

- 10. Z. Wang, X. Liu, B. Xu, and Z. Wu, Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 51 (2015) 130-136.

-

- 11. A. Bhattacharya, C.M. Parish, T. Koyanagi, C.M. Petrie, D. King, G. Hilmas, W.G. Fahrenholtz, S.J. Zinkle, and Y. Katoh, Acta Mater. 165 (2019) 26-39.

-

- 12. S. Kravchenko, D.Y. Kovalev, I. Korobov, G. Kalinnikov, S. Konovalikhin, N.Y. Khomenko, and S. Shilkin, Inorg. Mater. 55[5] (2019) 458-461.

-

- 13. G. Fairbank, C. Humphreys, A. Kelly, and C. Jones, Intermetallics 8[9-11] (2000) 1091-1100.

-

- 14. K. Spear, E. Wuchina, and E.D. Wachsman, Electrochem. Soc. Interface 15[1] (2006) 48.

-

- 15. X. OuYang, F. Yin, J. Hu, Y. Liu, and Z. Long, J. Ph. Equilibria Diffus. 38[6] (2017) 874-886.

-

This Article

This Article

-

2025; 26(6): 1086-1089

Published on Dec 31, 2025

- 10.36410/jcpr.2025.26.6.1086

- Received on Sep 4, 2025

- Revised on Oct 2, 2025

- Accepted on Oct 2, 2025

Services

Services

Shared

Correspondence to

Correspondence to

- Shouliang Lai

-

Hunan University of Technology, 412000, Zhuzhou, Hunan, China

Tel : +86-0731-22183693 Fax: +86-0731-22183936 - E-mail: laishouliang@hut.edu.cn

Copyright 2019 International Orgranization for Ceramic Processing. All rights reserved.

Copyright 2019 International Orgranization for Ceramic Processing. All rights reserved.