- Controlling shrinkage and enhancing drying kinetics in ceramic clay bodies through chamotte particle size and content optimization

Kaiyang Luoa,*, Weijun Yea and Zhongyuan Lib

aDepartment of Animation, Huanghuai University, Zhumadian 463000, China;

bSchool of Architectural Engineering, Huanghuai University, Zhumadian 463000, ChinaThis article is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Chamotte-tempered clay bodies because of their improved dimensional stability and regulated drying and firing behavior, have become the material of choice for large-scale and structurally challenging clay sculpture. This study assesses the effects of chamotte particle size, content, and physical properties on mechanical performance, shrinkage, and workability in sculptural clay compositions. The use of chamotte, an inert, pre-fired grog, minimizes warpage and cracking in large or intricate sculptural shapes by drastically reducing drying and firing shrinkage. For outdoor installations and high-temperature artistic procedures, refractory inclusions also improve handling stability, load-bearing capability after firing, and tolerance to abrupt temperature changes. Coarse chamotte was shown to improve stiffness and sustain massive shapes, while finer chamotte boosted strength and enabled accurate detailing, according to experimentally obtained performance data and findings published in the ceramic literature. The findings highlight how crucial it is to choose the right chamotte grading and content in order to attain a harmonious blend of workability, structural dependability, and long-term durability. In order to assist artists, designers, and conservators in creating optimal clay bodies for sophisticated sculptural applications, this study offers a useful framework based on materials science.

Keywords: Chamotte-tempered clay, Sculptural workability, Shrinkage, Structural stiffness.

The production of ceramic sculptures, especially those with significant weight, large size, or complex, uneven wall thicknesses, requires the use of specially designed ceramic materials [1]. Although traditional plastic clays offer excellent workability and rheological properties necessary for detailed work, they are naturally prone to dimensional instability when used in large-scale structures [1, 2]. This vulnerability stems from the basic composition of these clays, which are mainly made up of extremely fine, plate-like aluminosilicate particles. This structure results in a large surface area that demands a high water content to become pliable [3]. As a result, these materials experience substantial volume reduction during drying and firing. In large-scale sculptural applications, this inherent high volumetric shrinkage surpasses limited tensile strength of the material, causing visible defects such as warping, distortion, and, importantly, the collapse of unsupported forms in their unfired state [4]. The main issue is the inverse relationship between desired aesthetic qualities and structural needs: the very features that provide high plasticity, fine particle size and extensive inter-particle surface area, are the direct mechanical reasons for severe structural failure (high shrinkage and low cohesive strength) when scaled up. Therefore, engineered solutions must introduce heterogeneity to separate these conflicting material requirements.

Structural failure in large ceramic objects is primarily a kinetic issue, driven by the uneven buildup of stress during thermal and moisture processing [5, 6]. This stress accumulation happens in two main phases: drying and firing. In the initial drying phase, stress gradients form due to uneven moisture loss [7]. As the outer layer of a thick-walled piece dries quickly and starts to contract, the inner core remains moist. This difference in volumetric contraction generates significant internal shear stresses, as the rapidly shrinking exterior tries to pull the dimensionally stable, still-moist interior. If the movement of moisture from the core to the surface is hindered, a trait of fine-grained plastic clays, these stresses build up, resulting in defects like cracking and lamination. Thermal stresses persist and often intensify during the subsequent firing phase. Major stresses occur during the breakdown of hydrates (dehydroxylation) and, importantly, during the rapid, reversible volumetric changes linked to crystallographic phase transformations, such as the α−β quartz inversion, which takes place at around 573 oC [8]. These thermal variations create strain within the material matrix. When there are large temperature differences across the thick wall, especially during rapid heating or cooling, the differential expansion and contraction lead to accumulated tensile strain, which appears as microcrack formation and eventual catastrophic failure [9]. The material’s ability to withstand these stages is directly constrained by its capacity for quick fluid and gas transfer, as well as its inherent fracture resistance [10].

The primary functional outcome of adding chamotte is the decrease in total linear shrinkage. This is accomplished by the mechanical displacement of the shrinking clay matrix with the dimensionally stable filler material [11]. By replacing a portion of the high-shrinkage plastic clay with non-shrinking chamotte, the overall volumetric contraction of the composite body is significantly reduced [12]. Chamotte serves as an inert volume filler, effectively diluting the amount of fine clay particles that contribute to capillary shrinkage. Quantifiable improvements highlight the significant impact: in one formulation, a high-shrinkage body with a typical fired shrinkage of 5.5% experienced a reduction to 2.5% after adding 15% 20-48 mesh grog and 15% 70 mesh silica sand, while maintaining the desired level of vitrification. This stabilization is crucial for complex or thick-walled forms where minor dimensional deviations can lead to significant structural warping. Research indicates that adding grog often reduces the dry strength, measured as the Modulus of Rupture, of the ceramic body. This reduction in strength occurs because the chamotte particles replace the finer clay particles necessary for maximum particle interlocking and the establishment of strong Van der Waals forces, which are the primary source of cohesive strength in the dry state. For instance, tests have shown that while a 10% addition of 50-80 mesh grog reduces drying shrinkage by approximately 0.5% - 0.75%, it also compromises dry strength, causing cracks to follow a jagged, rather than clean, path when failure occurs. This establishes a critical engineering compromise: maximizing dimensional stability (requiring high grog content) risks mechanical failure in the fragile dry state due to reduced cohesive strength. Successful formulation requires careful optimization of grog concentration and particle size distribution to balance these opposing effects.

The clay body formulations were prepared by incorporating chamotte at 0, 10, 20, and 40 wt%, using two particle size fractions: fine (<250 µm) and coarse (500–1000 µm). All raw materials were oven-dried at 110 °C for 24 h and homogenized using a laboratory mechanical mixer (IKA RW20) to ensure uniform distribution. Test bars for shrinkage measurements were produced following ASTM C210 – Standard Test Method for Linear Drying Shrinkage of Nonmetallic Materials, while cylindrical specimens (25 mm diameter × 30 mm height) for permeability and porosity measurements were formed using a hydraulic press (Carver Model 3851, USA) at 20 MPa. After air-drying, specimens were dried to constant mass in a Memmert UF110 drying oven. Firing was carried out in an electric programmable kiln (Nabertherm LT 15/13) at 1180, 1240, and 1300 °C, using a heating rate of 5 °C/min and a 1 h soaking period at the peak temperature. Linear and volumetric shrinkage were determined by measuring pre- and post-firing dimensions using a Mitutoyo 0.01 mm digital caliper, and calculations were performed in accordance with ASTM C326 – Linear Thermal Expansion of Ceramic Whiteware for dimensional change evaluation. Permeability testing followed ASTM C577 – Permeability of Refractories, using a steady-state air flow permeability apparatus (Dandong BET-300A) where air flow rate and pressure drop were recorded to calculate Darcy permeability. Total open porosity was measured using the Archimedes water immersion method following ASTM C20 – Apparent Porosity, Water Absorption, and Bulk Density of Burned Refractory Brick, employing a precision electronic balance (Shimadzu AUW220D, 0.1 mg accuracy) for dry, saturated, and suspended mass measurements.

All tests were performed in triplicate, and the mean values were used to produce the shrinkage, permeability, and porosity trends with respect to chamotte content and particle size. The stabilizing effect of chamotte persists even during the high-temperature firing phase. Due to its high refractory nature and the fact that it has already reached maximum densification during its own calcination process (1400 oC-1600 oC), chamotte remains dimensionally stable during the application firing [13]. The primary function of reducing fired shrinkage is accomplished through volumetric dilution. By adding chamotte, the volume of material that can densify through sintering (the fine clay matrix) is proportionally decreased. This reduces the overall linear firing shrinkage and lessens shape deformation caused by stress accumulation during the final densification stage, aiding in the creation of complex, large-scale sanitaryware and sculptural pieces.

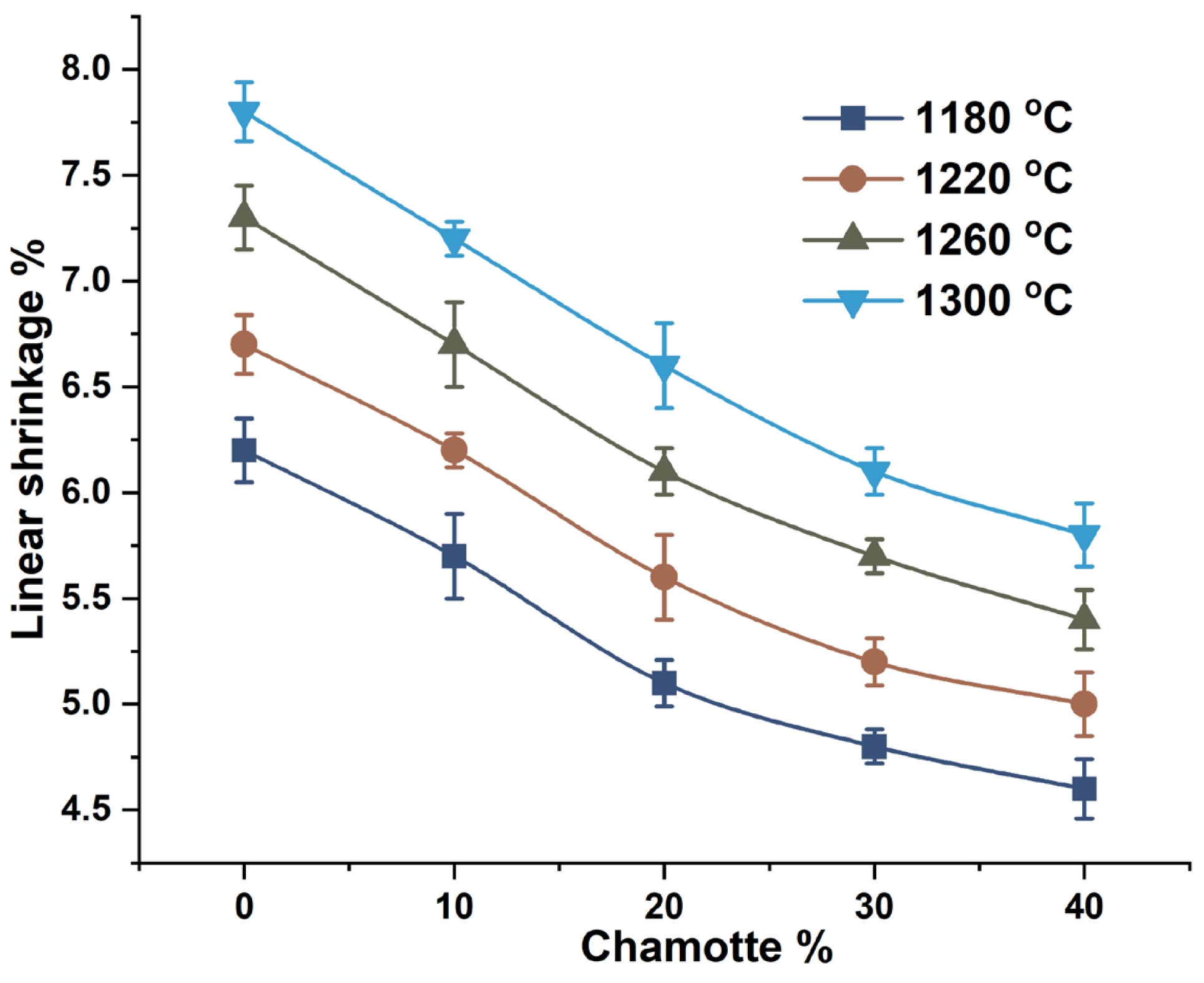

The findings show a strong inverse relationship between chamotte content and linear shrinkage at all firing temperatures (1180-1300 °C). In particular, linear shrinkage drops from roughly 6-8% for pure clay (0% chamotte) to 4.5%-5.5% at 40 wt% chamotte (Fig. 1). This decrease suggests that chamotte limits particle rearrangement and densification during sintering, acting as a dimensional stabilizer. Chamotte takes up space in the clay matrix since it is a pre-fired refractory material that is chemically inert and does not significantly shrink [14]. As a result, it mitigates overall dimensional changes by lowering the effective clay proportion that causes shrinkage. The relative decrease in shrinkage with increasing chamotte is continuous, but somewhat higher shrinkage values at higher temperatures can be explained by improved sintering kinetics, which encourage particle bonding and densification. For thick-walled ceramics, tiles, or sculptural elements where drying or firing-induced cracking is an issue, the data indicate that even modest chamotte additions (10-20 wt%) are adequate to control linear shrinkage.

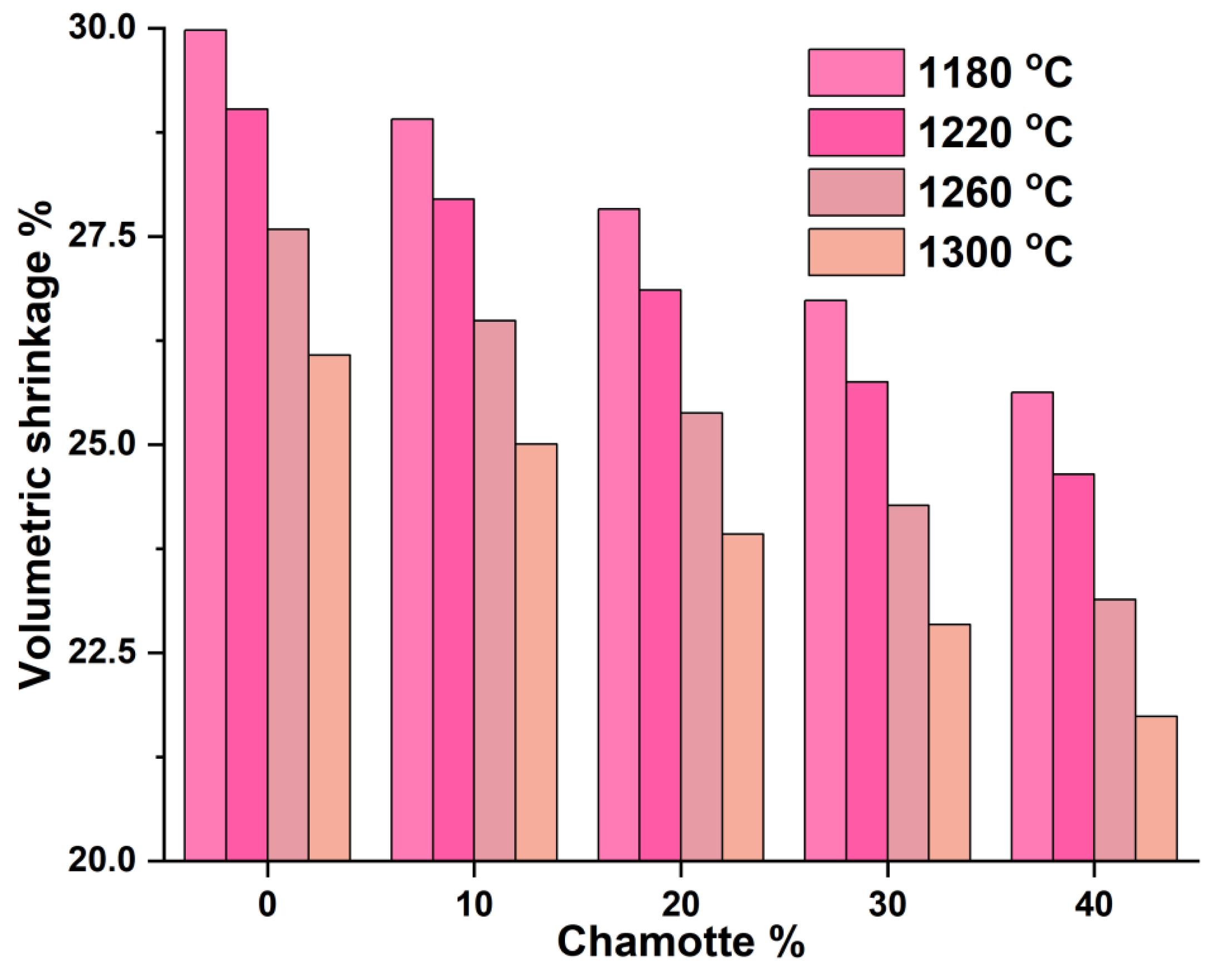

Similar to linear shrinkage, volumetric shrinkage gradually decreases from ~27-29% in unaltered clay to ~22-25% at 40 wt% chamotte (Fig. 2). Due to the combined effects of matrix densification and the limited mobility of clay particles imposed by chamotte, the decrease is somewhat increased at higher firing temperatures. The shrinkable volume is reduced by replacing a portion of the shrinkable clay with non-shrinking chamotte, which lessens internal tension buildup during drying and firing. Differential shrinkage can cause warping or microcracking in components with complicated geometries, making this effect especially pertinent. As a result, chamotte addition reduces volumetric stresses in the clay body while simultaneously stabilizing dimensions and serving as a microstructural buffer.

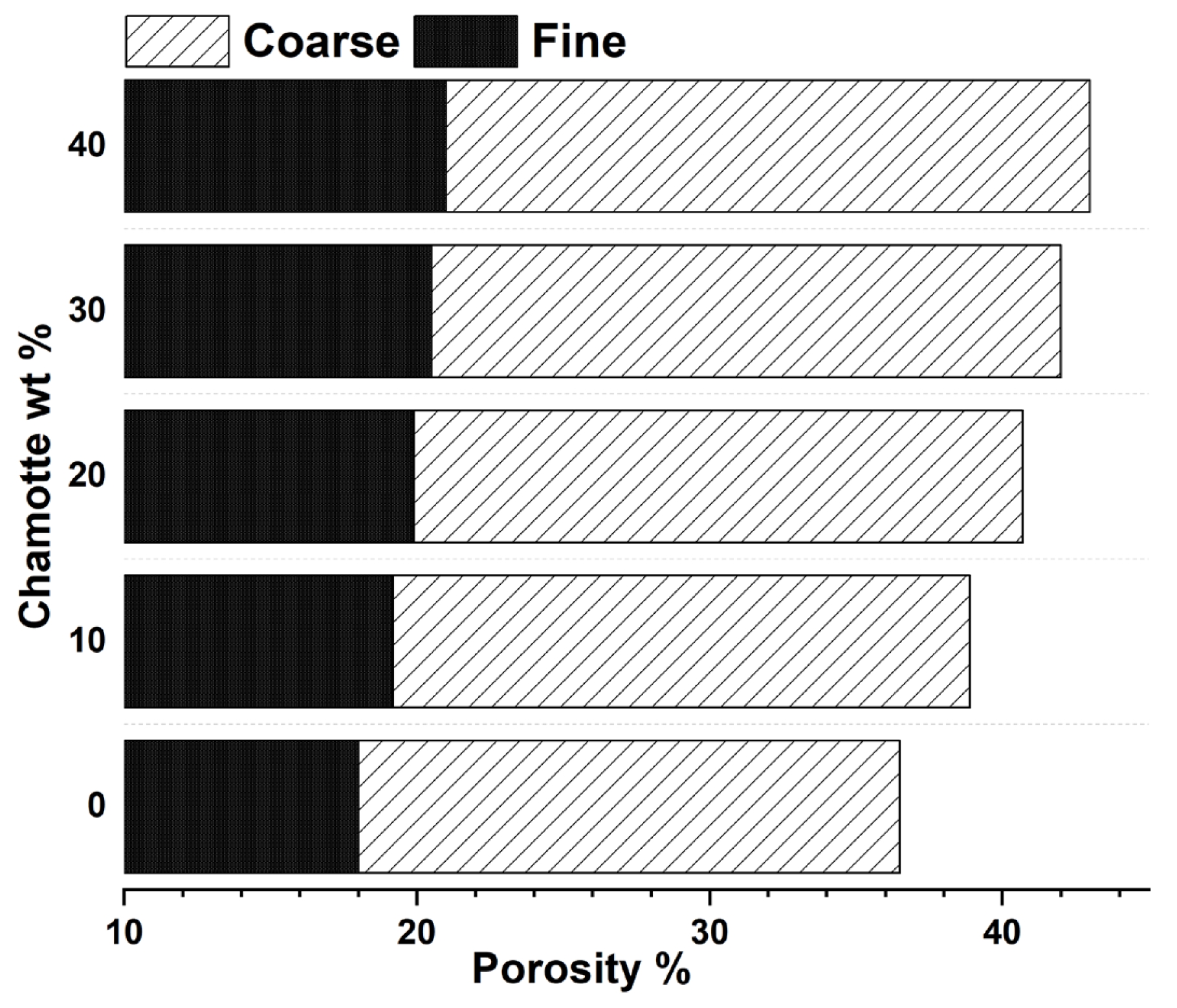

A fundamental cause of drying defects in thick-walled ceramics is the restriction of moisture transport through the dense, fine-grained clay matrix. Coarse chamotte produces far more porosity than fine chamotte, and total porosity rises almost linearly with chamotte concentration. Total porosity reaches around 44% for coarse chamotte and 22% for fine chamotte at 40% weight percent. Larger interstitial gaps between particles, which allow water to escape during drying, are thought to be the cause of the increased porosity in coarse chamotte systems. The observed increase in permeability is correlated with this porosity enhancement, suggesting that chamotte improves drying kinetics by selectively altering the microstructure in addition to stabilizing dimensions. These findings imply that the mechanical integrity and drying performance of ceramic bodies can be optimized by varying the chamotte content and particle size. Chamotte directly addresses this kinetic limitation by modulating the permeability of body. Chamotte particles are generally much coarser than the surrounding clay matrix and introduce pathways of high-flow macro-porosity into the fine capillary structure of the clay. This enhanced porosity and permeability facilitate the rapid and homogeneous evacuation of water during drying Fig. 3. The chamotte particles act as micro-channels, reducing the differential pressure head that typically develops between the saturated core and the rapidly drying surface. By ensuring the internal core loses moisture at a rate closer to the exterior rate, the material structure resolves the genesis of internal shear stresses caused by moisture gradients, directly mitigating defects such as lamination, cracking, and crow’s feet patterning. This kinetic homogenization ensures a more predictable and uniform volumetric contraction throughout the entire mass.

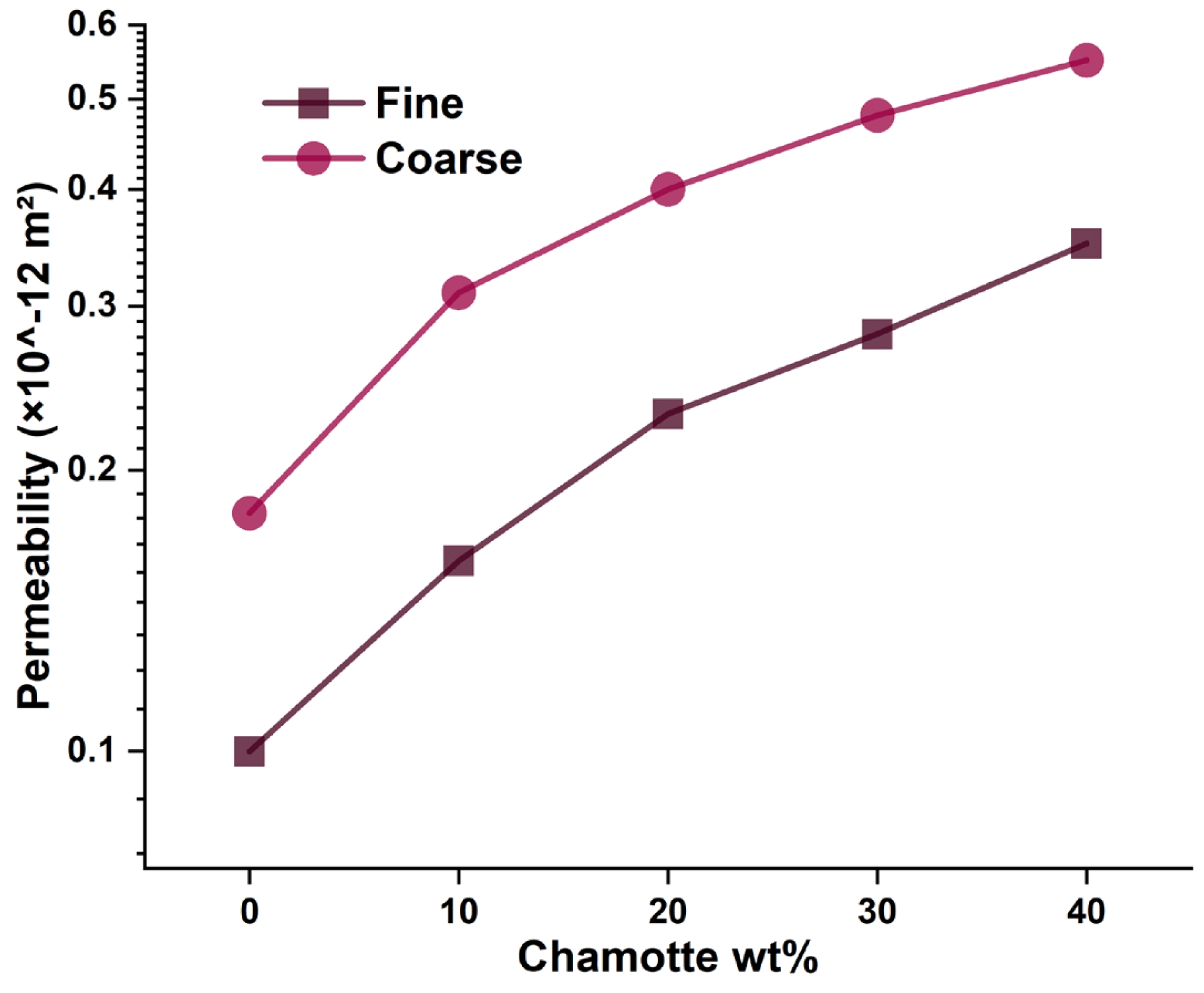

For both fine and coarse particle sizes, permeability rises with chamotte content; coarse chamotte consistently shows higher permeability than fine (Fig. 4). Although fine chamotte only reaches ~0.35×10-¹² m² coarse chamotte reaches ~0.54×10-¹² m² at 40 wt.%. The difference results from the particle size effect: fine chamotte creates smaller, more evenly distributed pores that offer moderate permeability and preserving structural cohesion, whereas coarse chamotte introduces larger inter-particle voids and channels that improve water vapor transport during drying. Increased permeability in bodies containing coarse chamotte makes it easier for moisture to migrate, which lowers the risk of breaking in thick or dense ceramics and reduces internal drying stresses. These results demonstrate how important chamotte particle size is in modifying the transport characteristics of ceramic materials.

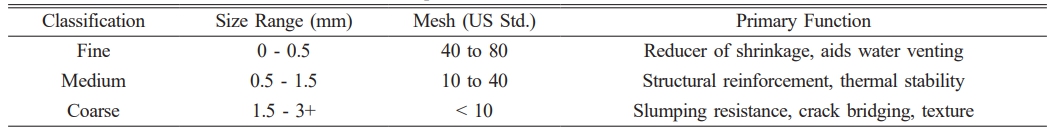

A key consideration in advanced ceramic engineering is achieving maximum densification and shrinkage reduction through optimal particle packing, often utilizing smaller particles fill the interstices of the larger ones. For sculptural clay bodies, however, the priority often shifts from maximum density to maximum permeability and crack arrest. Therefore, formulators often employ the highest percentage of the largest tolerable particles, as this yields the greatest reduction in shrinkage and the least reduction in plasticity for a given volume fraction. The following table summarizes the functional role of different particle size classifications in sculptural bodies:

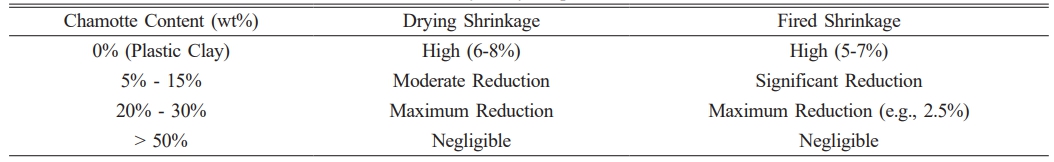

The ideal amount of chamotte is a carefully crafted balance based on the specific functional needs of the application. For typical sculptural or hand-building clay bodies, where some level of plasticity is necessary for shaping, chamotte is typically added in amounts ranging from 15% to 25% by weight. This proportion ensures the required structural strength, high permeability, and control over shrinkage while maintaining enough plasticity for manual shaping and detailing. On the other hand, specialized industrial or refractory clay bodies, which demand minimal shrinkage and maximum durability, may contain 50% to 90% or more grog. These non-plastic compositions form the rigid framework of refractories and are shaped using industrial techniques like pressing or casting, rather than traditional plastic methods. The formulation must consider the trade-off mentioned: maximum mechanical strength is often achieved with moderate loading (e.g., 5%-15%), while maximum dimensional stability requires higher loading (e.g., 20%-30% or more) to achieve the necessary inert volume displacement. The data underscores the range needed for optimal performance: Table 1 Table 2

|

Fig. 1 Linear shrinkage vs. chamotte content. Linear shrinkage decreases with increasing chamotte content across all firing temperatures. |

|

Fig. 2 Volumetric shrinkage vs. chamotte content. Volumetric shrinkage shows a similar decreasing pattern, showing decreased shrinkable volume and less internal stress buildup during drying and burning. |

|

Fig. 3 Total porosity vs. chamotte content. |

|

Fig. 4 Permeability vs. chamotte content. Permeability rises with higher chamotte content, with coarse chamotte showing consistently higher values than fine chamotte. |

Chamotte-tempered clay bodies offer an advanced material solution by converting dimensionally unstable plastic clay into a high-performance ceramic matrix composite reinforced with particles. This comprehensive mechanism addresses challenges throughout the production process, from initial strength to thermal durability. By incorporating refractory, inert particles, chamotte mechanically offsets the shrinking volume, regulates internal porosity to balance moisture and gas transport rates, and forms a physical framework that prevents slumping and halts the spread of microcracks. The stabilization achieved through chamotte significantly broadens the performance capabilities of clay bodies, allowing for the creation of large-scale and thick-walled ceramic structures with reliable dimensional accuracy and improved fracture toughness. Future research should focus on the detailed thermal engineering of these composites. It is important to pay particular attention to improving the connection between the chamottes coefficient of thermal expansion, the vitrification temperature of the matrix, and the occurrence of critical phase changes, such as quartz inversion. This will help further reduce internal thermal stresses and ensure full compatibility with high-performance glazes, preventing defects like glaze shivering. Additionally, ongoing refinement of chamotte particle size distribution and loading ratios will enhance green strength while preserving acceptable final mechanical properties, advancing the technical capabilities of architectural and large-scale sculptural ceramics.

This work were supported by the General Project of Humanities and Social Sciences Research in colleges and universities of Henan Province (No. 2023ZZJH350), the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (No. 2023M732726), and the Key Research Project of Colleges and Universities of the Department of Education of Henan Province (No. 24B413006).

- 1. R.C. Buchanan, "Ceramic materials for electronics" (CRC press, 2018).

-

- 2. F. Zuo, Q. Wang, Z.-Q. Yan, M. Kermani, S. Grasso, G.-L. Nie, B.-B. Jiang, F.-P. He, H.-T. Lin, and L.-G. Wang, Scr. Mater. 221 (2022) 114973.

-

- 3. P.A. Ciullo, in "Industrial Minerals and Their Uses" (William Andrew Publishing, 1996) pp. 17-82.

-

- 4. S. Janga, U.V.N. Rao, A.N. Raut, and N.V.S. Kumar, J. Adv. Res. Micro Nano Eng. 35[1] (2025) 21-44.

-

- 5. Y. Kadin, S. Strobl, C. Vieillard, P. Wijnbergen, and V. Ocelik, Procedia Struct. Integr. 7 (2017) 307-314.

-

- 6. O. Gavalda-Diaz, E. Saiz, J. Chevalier, and F. Bouville, Int. Mater. Rev. 70[1] (2025) 3-30.

-

- 7. W. Liu, X. Wei, N. Zhang, J. Li, L. Li, L. Li, W. Cao, X. Duan, and G. Ren, J. Food Sci. 90[6] (2025) e70324.

-

- 8. S.E. Johnson, W.J. Song, A.C. Cook, S.S. Vel, and C.C. Gerbi, Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 553 (2021) 116622.

-

- 9. P. Monash, and G. Pugazhenthi, Int. J. Appl. Ceram. Technol. 8[1] (2011) 227-238.

-

- 10. H. Scholz, J. Vetter, R. Herborn, and A. Ruedinger, Int. J. Appl. Ceram. Technol. 17[4] (2020) 1636-1645.

-

- 11. A.M. Muhaba, Mater. Res. Express 12[10] (2025) 105102.

-

- 12. K. Belhouchet, A. Bayadi, H. Belhouchet, and M. Romero, Bol. Soc. Esp. Ceram. Vidr. 58[1] (2019) 28-37.

-

- 13. M.A. Campos, V.A. Paulon, and A.M. de Argollo Ferrão, in Concrete made with alternative fine aggregates: the reuse of porcelain electrical insulators 2018 (Trans Tech Publ, 2018) p. 185-190.

-

- 14. F.M. Candel, and J.A.A. Galea, J. Ceram. Process. Res. 25[3] (2024) 465-473.

-

This Article

This Article

-

2025; 26(6): 1081-1085

Published on Dec 31, 2025

- 10.36410/jcpr.2025.26.6.1081

- Received on Nov 13, 2025

- Revised on Dec 2, 2025

- Accepted on Dec 4, 2025

Services

Services

- Abstract

introduction

methodology

results and discussion

conclusion

- Acknowledgements

- References

- Full Text PDF

Shared

Correspondence to

Correspondence to

- Kaiyang Luo

-

Department of Animation, Huanghuai University, Zhumadian 463000, China

Tel : 19139531399 Fax: 03962912851 - E-mail: 554667014@qq.com

Copyright 2019 International Orgranization for Ceramic Processing. All rights reserved.

Copyright 2019 International Orgranization for Ceramic Processing. All rights reserved.