- Defect identification and spectral analysis of nanosized SnS2-ZnO mixture for enhanced UV light absorption

Shih-Ming Tsenga, Alex C.H. Leeb,*, Omid Ali Zargarb, Chun-Chieh Huangc, Jow-Lay Huanga and Horng-Hwa Lub,*

aDepartment of Materials Science and Engineering, National Cheng Kung University, Tainan 70101, Taiwan, R.O.C.

bDepartment of Mechanical Engineering, National Chin-Yi University of Technology, Taichung 411030, Taiwan, R.O.C.

cDepartment of Semiconductor and Electro-Optical Engineering, Southern Taiwan University of Science and Technology, Tainan 710301, Taiwan, R.O.C.This article is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Nano-sized tin sulfide (SnS₂) and zinc oxide (ZnO) particles were synthesized using the hydrothermal and precipitation methods, respectively. Subsequently, the two nano-powders were physically mixed by direct stirring at different molar ratios. The X-ray diffraction patterns of SnS2-ZnO composites showed that the peaks of SnS2 and ZnO had no impurity. The photoluminescence spectra results suggested that as ZnO existed in the SnS2 matrix, the amount of the anion/cation vacancies or ionized defects was associated with ZnO content. The X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy revealed that the bonding energy of Zn2+ and Sn4+ shifted to higher and lower energy levels, respectively, probably resulting in the formation of heterointerface and the change in Fermi level of the synthesized nanocomposites. The results from structural and spectroscopic-analyses suggested that the enhanced ultraviolet light absorption of SnS2 matrix containing 20 mol% ZnO was attributed to charge transfer at hetero-interfaces between amorphous ZnO nanoparticles and SnS2 nanocrystallites.

Keywords: Tin sulfide nanoparticles, Zinc oxide, Defect, Ultraviolet light absorption.

Inorganic tin sulfide (SnS₂) has low toxicity, high sustainability, low-cost fabrication, chemical stability, and abundance in nature, making it suitable for large-scale production [1]. It has a narrow bandgap of approximately 2.1 eV, capable of absorbing ultraviolet (UV) light and part of the visible spectrum. Meanwhile, Liu et al. [2] reported that SnS2 possessed strong photon-capturing capability. These features demonstrate why it can be used in high-speed photodetectors [3], solar cells [4], and water splitting [5]. On the other hand, SnS2 has faradic behavior and thus can be applied for electrode materials in supercapacitors [6] or lithium-ion batteries [7, 8]. The main reason for this is that SnS₂ exhibits excellent electronic conductivity. Many synthesis methods have been employed to prepare SnS2 nanoparticles, including the wet chemical approach [1], chemical vapor transport [9], physical vapor transport [10], molecular beam epitaxy [11], and spray pyrolysis [12]. Gadore et al. [13] recently adopted green synthesis approach to prepare SnS2/HAp photocatalysts with superior photodegradation efficiency. Among them, the wet chemical approach is regarded as one of the high-yield processing methods without expensive instruments. SnS2 nanoparticles were considered to increase energy bandgap and exhibit strong photocatalytic activity, enabling the degradation of the enrofloxacin antibiotic [14]. The above literature shows that the bandgap of nanometer-sized SnS₂ increases from 2.31 eV to 2.91 eV as the particle size decreases (due to the quantum confinement effect) [15]. Therefore, the bandgap of nanometer-sized SnS₂ can be extended to 2.5 eV or even higher, enabling it to absorb UV light.

It has been reported that nanostructured zinc oxide (ZnO) with diverse morphologies, such as spherical particles [16], flower-like structures [17], and nanorod architectures [18], can be synthesized through various chemical methods. Monolithic ZnO has been extensively utilized in semiconductor devices, including varistors [19] and scintillators [20]. Moreover, the integration of ZnO with other nanomaterials, for instance ZnO@ZIF-8 [21] or Ag–ZnO heterojunction composites [22], has attracted increasing attention due to their enhanced photocatalytic performance. The ZnO bandgap is approximately 3.37 eV [23]. The energy of the ZnO bandgap is higher than that of visible light. This causes ZnO not to absorb visible light. This phenomenon causes ZnO to exhibit a high level of transparency in the visible spectrum. In the UV region, ZnO demonstrates a sharp decrease in transmittance. This phenomenon forms an absorption edge, which leads to excellent UV absorption efficiency. ZnO can be formed into various morphologies and sizes depending on the synthesis method, exhibiting 1D, 2D, or 3D structures. According to the literature [24-26], flower-like ZnO exhibits improved physicochemical properties, making it suitable for photocatalysis, rapid ethanol sensing, photoanode materials (for dye-sensitized solar cells), blood vessel detection, and photocatalytic activity. Due to the superior electron transport properties of flower-like ZnO, this study attempts to use it as a secondary phase for environmentally friendly SnS2 nanopowders, aiming for potential applications as UV light protective coatings.

Both the TiO2-ZnO and SnS2-ZnO nanocomposites can be applied for UV light absorption. The TiO2-ZnO nanocomposite exhibits similar band gaps between TiO2 and ZnO. On the other hand, the SnS2-ZnO shows a more considerable bandgap difference between SnS2 and ZnO. For specific thin film applications, SnS2, which absorbs visible light, demonstrates excellent antibacterial properties and high efficiency in decomposing pollutants. Although TiO2 and ZnO are widely used in UV-light-absorbing materials, SnS2 can exhibit photocatalytic activity under low-light indoor conditions. As a result, it is also a promising indoor antibacterial coating for future development. The SnS2-ZnO, with the discussion addressing UV absorption characteristics that have not yet been explored in the existing literature, will be investigated in the present study.

The SnS2 nanoparticles were prepared using the hydrothermal method. Tin tetrachloride and deionized water (D.I. water) were added to a beaker with a concentration of 0.125 M. After complete dissolution, thioacetamide (tin tetrachloride/thioacetamide molar ratio = 1/3) was added. During the hydrothermal synthesis of SnS₂, the preliminary stirring time generally ranges from 30 minutes to 2 hours. Mayandi et al. adopted a stirring time of 30 minutes and successfully obtained SnS₂ nanosheets with a layered structure and a single hexagonal phase orientation [27]. Rajendran et al. performed a one-hour stirring process, followed by microwave-assisted hydrothermal synthesis, to produce flower-like, single-phase SnS₂ structures [28]. Cho et al. used three different solvents to synthesize sheet-like, flower-like, and eclipse-like SnS₂ morphologies. However, their stirring time was only 5 minutes, and SEM observations revealed irregularly aggregated secondary particles [29]. Bin and Yin reported a facile fabrication of SnS microflower-graphene composite by precipitation method with a stirring time of 30 mins [30]. Based on these studies, it can be inferred that a stirring time of at least 30 minutes prior to the hydrothermal reaction is required to obtain more uniform SnS₂ particles. The solution was stirred at room temperature for 1 hour, then transferred to an autoclave and placed in an oven at 190 °C for 6 hours. After cooling to room temperature, D.I. water was added, and the solution was centrifuged at 6000 rpm for 15 minutes. This purification step was repeated three times. The final yellow residue was placed in an oven at 100 °C for 4 hours to obtain SnS2 nanoparticles.

The precipitation method was used to prepare ZnO. The pre-precipitation stirring process plays a crucial role in the nucleation of nano-ZnO crystallites. Wang et al. [16] investigated the preparation strategies of synthesizing nanosized ZnO via different precipitation routes with a stirring time of ~1 hour [5]. Mollaesmail et al. [31] successfully synthesized ZnO micro-flowers by precipitation method using a stirring time of 150 min; Vaezi [32] prepared SnO/ZnO nanocomposites via co-precipitation method under a stirring time of 2 hours; Muensit et al. [33] synthesized various antibacterial ZnO nanopowders by different chemical precursors under a stirring time of 1 hour. As reported in these literatures, the stirring time for nano-ZnO precipitation approacch is generally controlled larger than 30 minutes. The requirement is not limited to precipitation reactions; for example, in the solution combustion synthesis of ZnO nanomaterials, the precursor solution also requires a stirring time of 30 minutes [34]. Based on the above literature, a stirring time of at least 30 minutes is required during the solution-based process to ensure a homogeneous precursor solution. Thus, an uniform grain size distribution of ZnO nanoparticles can be obtained. Therefore, a stirring time of 1 hour was adopted in this study for precursor mixing, resulting in monolithic ZnO nanoparticles with a uniform grain size distribution. Zinc nitrate and D.I. water were added at a concentration of 0.01 M, then stirred at room temperature for 1 hour using a magnetic stirrer. Sodium hydroxide was added with a zinc nitrate/sodium hydroxide molar ratio of 0.5. Then, the mixture was stirred for another hour. In the next step, the solutions were allowed to stand at room temperature for 8 hours. Afterward, ethanol was added, and the mixture was centrifuged at 6000 rpm for 10 minutes. This washing procedure was repeated three times to remove impurities. The final white residue was placed in an oven at 100 °C for 2 hours to obtain ZnO crystal. This experiment denoted the synthesized ZnO as Z8.

SnS₂ nanopowders were blended with Z8 at different ratios and physically mixed through direct stirring. This physical blending method is quite simple and low-carbon-emitting, making it highly suitable for industrial processes. After stirring with D.I. water for 1 hour, add deionized water and ethanol in a 1:1 ratio and centrifuge at 6000 rpm for 10 minutes. The washing step was repeated three times, and finally, the product was placed in an oven at 100 °C for 2 hours. E8 was used to represent the powder mixture of Z8 with SnS2. Table 1 lists the powder mixture's sample designation and the corresponding molar ratio of ZnO.

X-ray diffractometer (XRD, Bruker D8 DISCOVER, Germany) was used to analyze the crystalline structure of the prepared composite materials. Copper targets were employed to excite characteristic X-rays (40 kV, 40 mA, λ=1.5418 Å). The scanning rate is 3°/min. The surface morphology of the powders was examined using high-resolution scanning electron microscopy (HR-SEM, Hitachi SU8000, Germany) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM, JEOL JEM-2100F CS STEM, Japan). X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS, JEOL JAMP-9500F Auger Electron, Japan) was used to analyze the chemical bonding and material composition. A UV/VIS/NIR spectrophotometer (Hitachi U4100, Japan) was employed to measure the optical properties in the 300-800 nm wavelength range. The defect types in the structure of pure zinc oxide, pure tin disulfide, and ZnO/SnS2 composites were analyzed using photoluminescence spectroscopy (PL, Jobin Yvon/Labram HR, France).

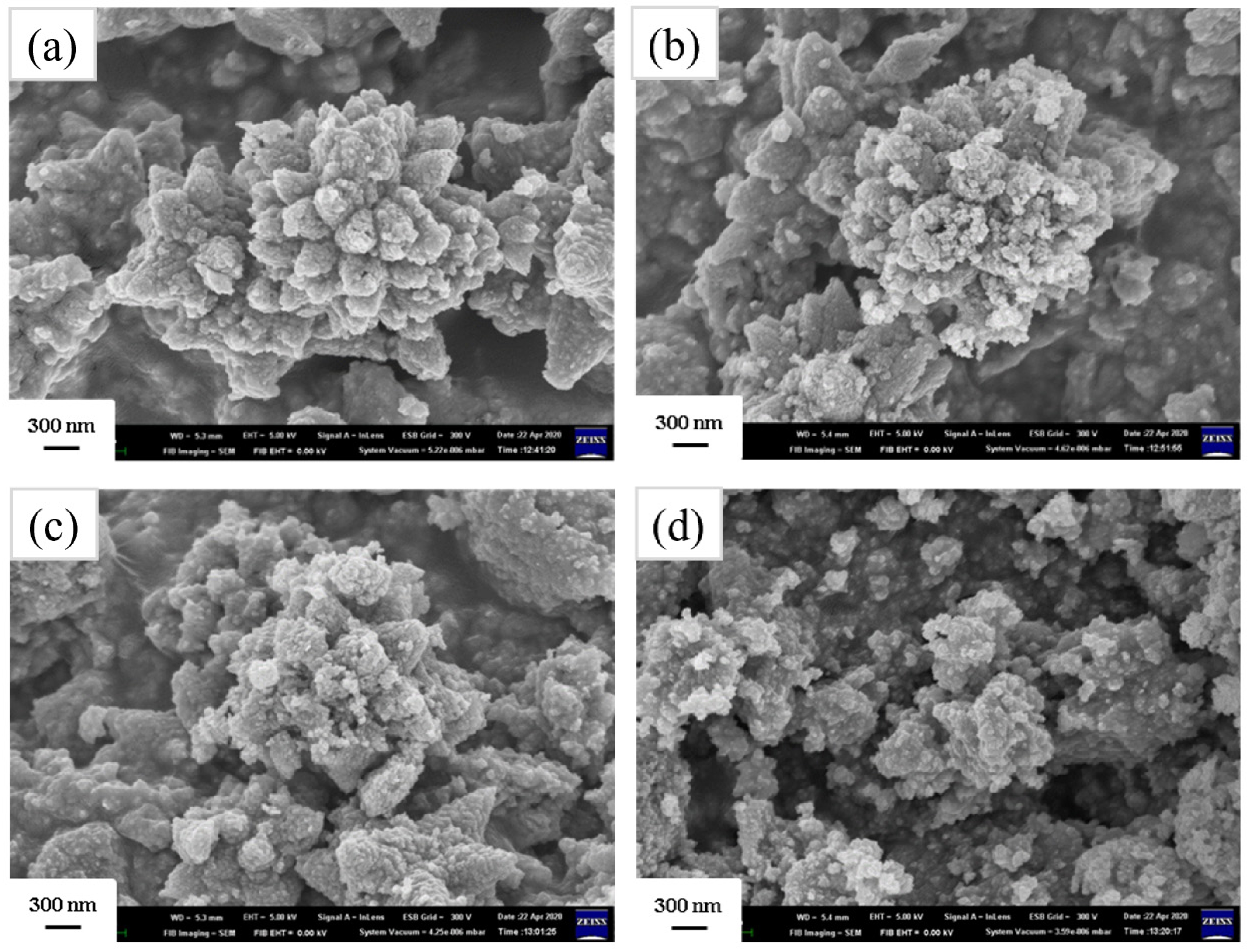

|

Table 1 Designation and molar ratio of the ZnO in the E8- series nanocomposites. The amounts of SnS2 and ZnO were measured in mmol. |

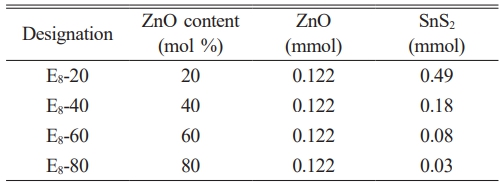

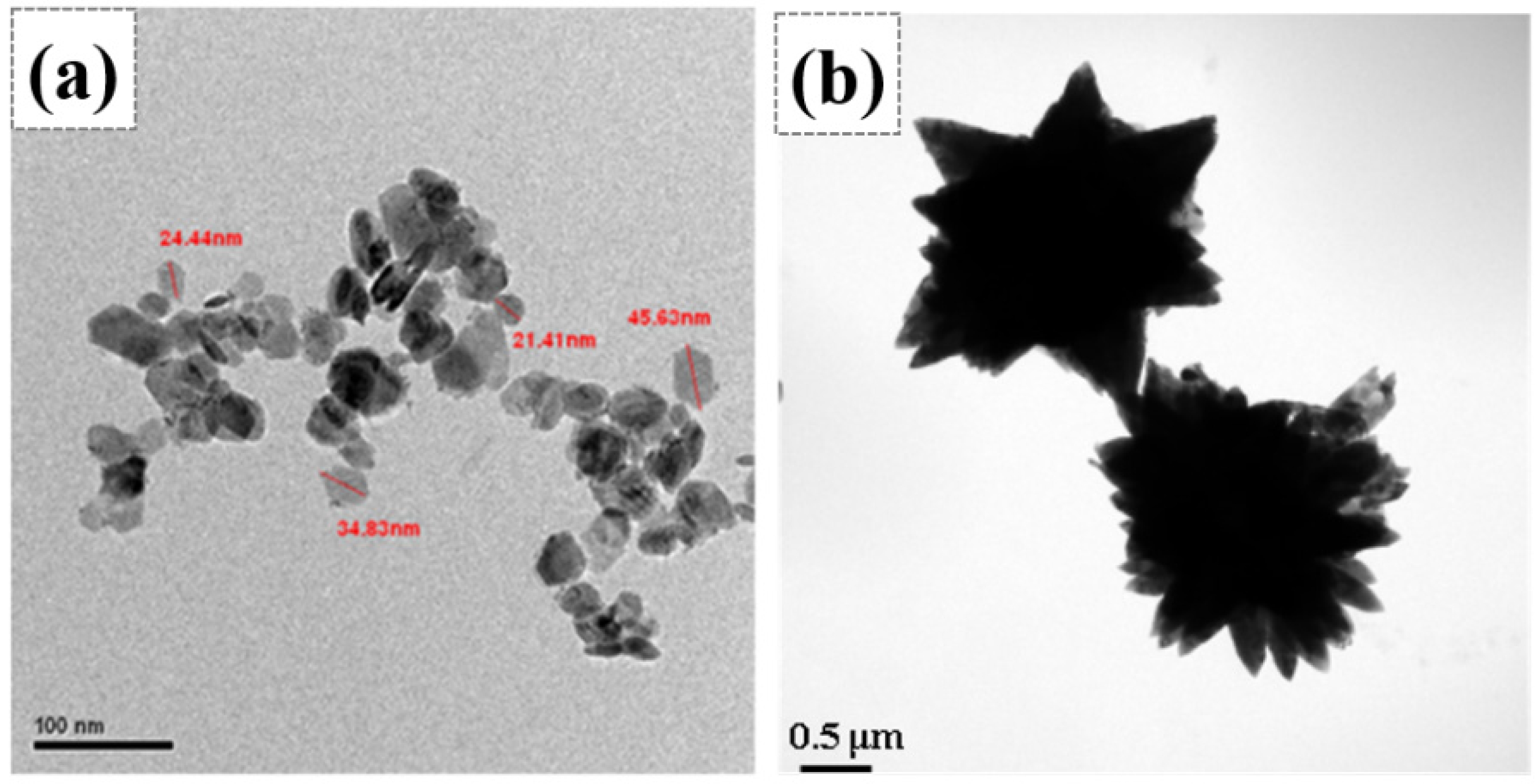

Fig. 1(a) and (b) present the TEM bright field images of SnS2 and Z8, respectively. The former showed a particle size of approximately 20-40 nm, and the latter exhibited flower-like morphology. Zgura et al. [35, 36] indicated that ZnO has a preferred growth orientation along the [001] direction. Therefore, ZnO grew along the [001] direction under precipitation reaction conditions through a self-assembly process, ultimately forming flower-like ZnO crystals. The driving force often originates from van der Waals forces or depletion forces generated by polymer interactions [37]. Fig. 2 demonstrates the XRD patterns of ZnO/SnS2 powder mixture. The SnS2 phase exhibited a 2T-type hexagonal berndtite structure (referencing JCPDs 23-0677) [38]. The other powder mixtures in different molar ratios of SnS2-ZnO displayed the existence of SnS2 and ZnO phases without impurity or peak shift. As the molar fraction of SnS₂ increases, the characteristic peak intensity of ZnO gradually decreases. In particular, for the E8-40 and E8-20 mixtures, the diffraction peaks of ZnO become very weak or nearly disappear. This result suggested that during the physical mixing process of the two powders, the ZnO crystallites in the E8-40 and E8-20 samples transform into a microcrystalline or even amorphous state, respectively. In contrast, the crystallinity of SnS₂ remains unchanged throughout the physical mixing process, with no observable change in its crystalline structure.

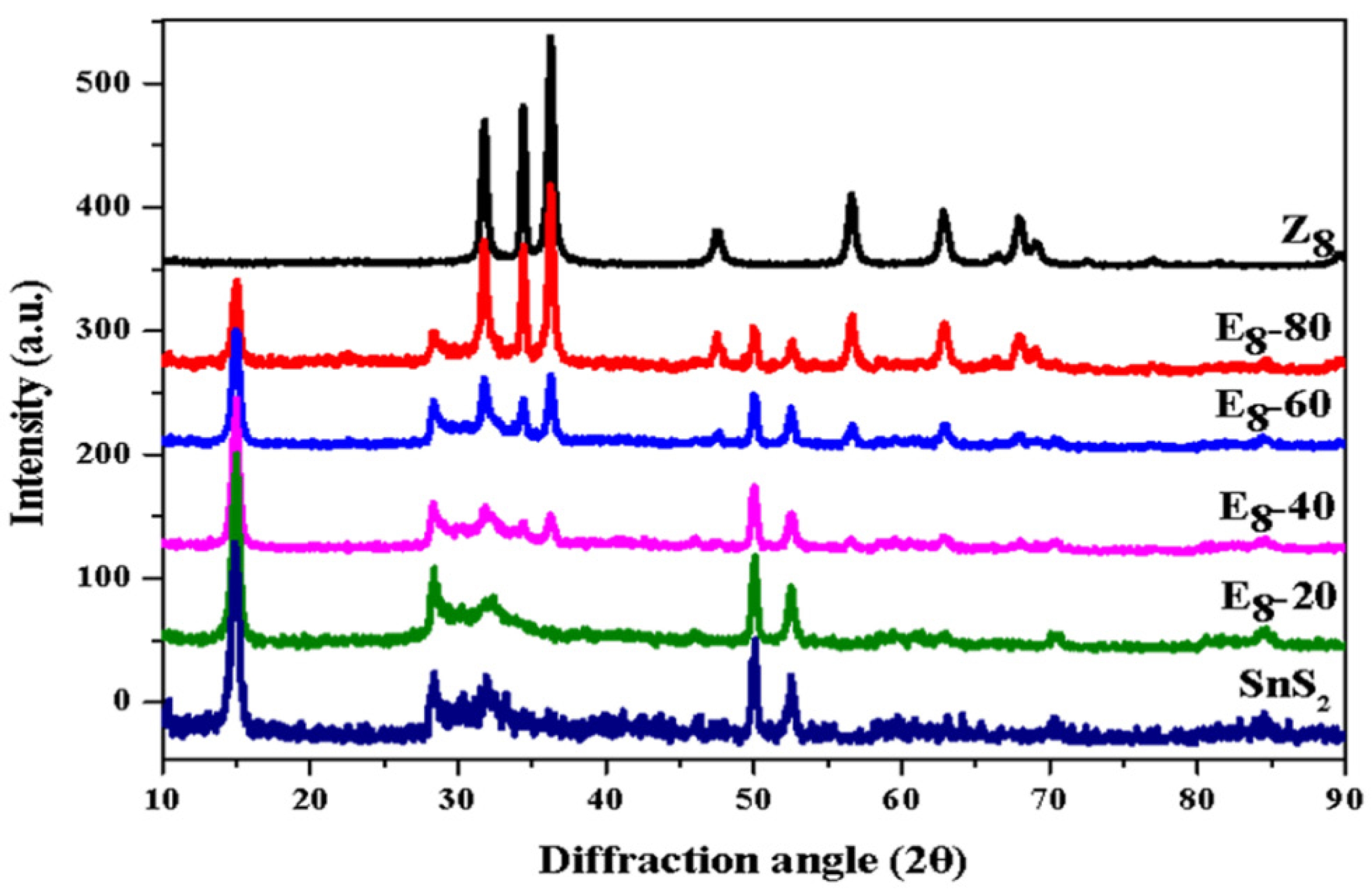

Fig. 3(a)-(d) displays the HRSEM images of powder mixtures with different molar ratios. It can be seen that the flower-like ZnO surfaces were covered with SnS2 nanoparticles. As the molar fraction of SnS2 increased, the flower-like ZnO was almost entirely covered by SnS2 nanoparticles, as shown in samples E8-40 and E8-20. Furthermore, it is observed that the morphology of flower-like ZnO does not significantly change with varying SnS2 contents.

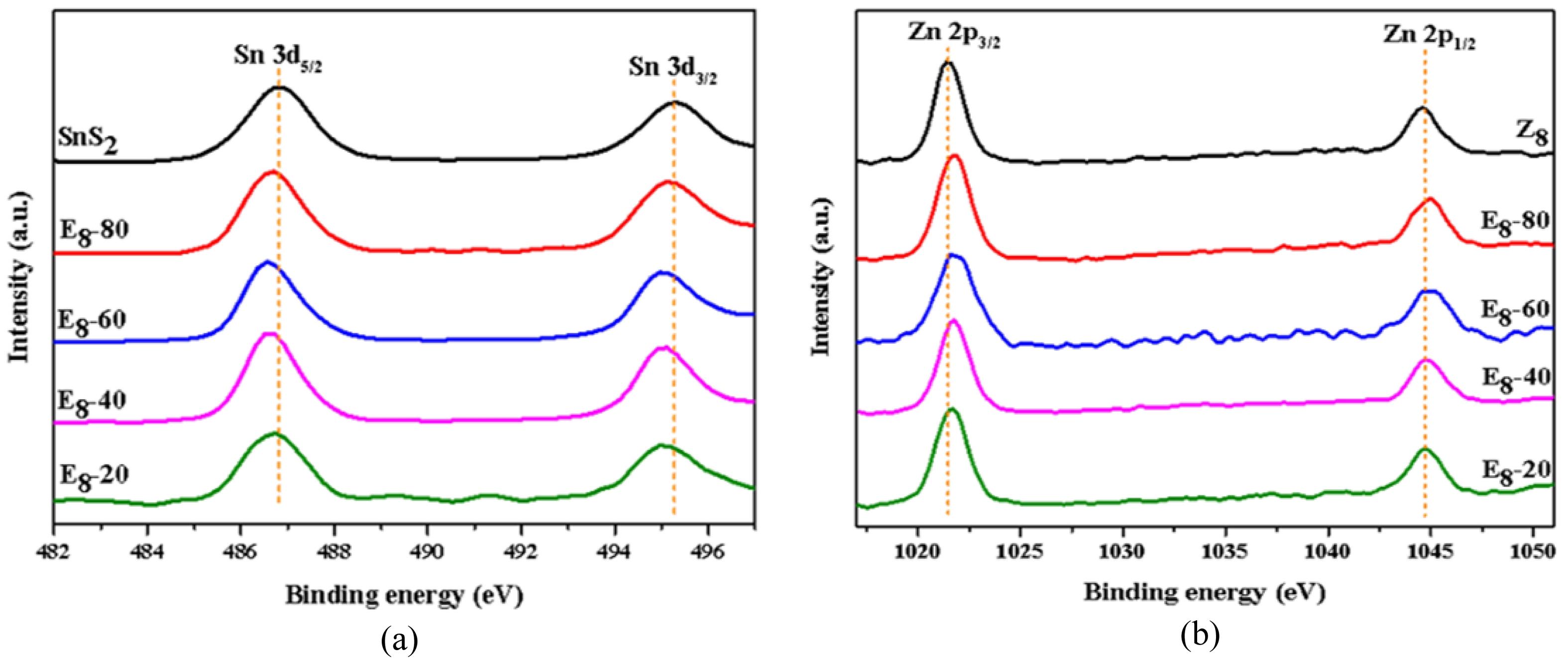

Fig. 4(a) shows the binding energy of the Sn 3d orbital, with 487.2 eV and 495.6 eV corresponding to the Sn⁴⁺ 3d₅/₂ and 3d₃/₂ characteristic peaks, respectively [39]. The results indicated that the two characteristic peaks shifted slightly to lower energy when adding ZnO. Fig. 4(b) shows the binding energy of Zn²⁺ in E8-series samples. According to reference materials, Zn 2p orbital has two binding energies, which fall at 1021.3 eV and 1044.5 eV, corresponding to 2p₃/₂ and 2p₁/₂, respectively [40]. It can also be observed that when the SnS₂ content increased, the binding energy of Zn²⁺ shifted slightly to higher energy. These observations show that the change in binding energy between Zn and Sn occurred in opposite directions. Iqbal et al. [41] pointed out that in fluorine-doped tin oxide-ZnO-NiO nanocomposites, the binding energies of Sn 3d₅/₂, Zn 2p₃/₂, and Ni 2p₃/₂ in the XPS spectra can respectively represent the valence band maximum in the energy level diagrams of SnO₂, ZnO, and NiO. Therefore, in this study, the increase in the binding energy of the Zn 2p orbital accompanied by the decrease in the Sn 3d orbital binding energy indicates a shift in the valence band maximum positions of ZnO and SnS₂, suggesting a band alignment that is likely related to electronic interactions at the heterointerface. According to the literature [42, 43], when SnS₂ and ZnO form a composite material, electrons migrate from SnS₂ to ZnO, which can be attributed to the different Fermi levels. The literature showed that the work function of SnS₂ was 4.2-4.5 eV, while for ZnO, it is 5.2-5.3 eV [44, 45]. This indicates that SnS₂ has a higher Fermi level relative to ZnO. Therefore, the electrons will transfer from the lower-work-function SnS₂ to the higher-work-function ZnO upon contact, until Fermi level alignment is achieved.

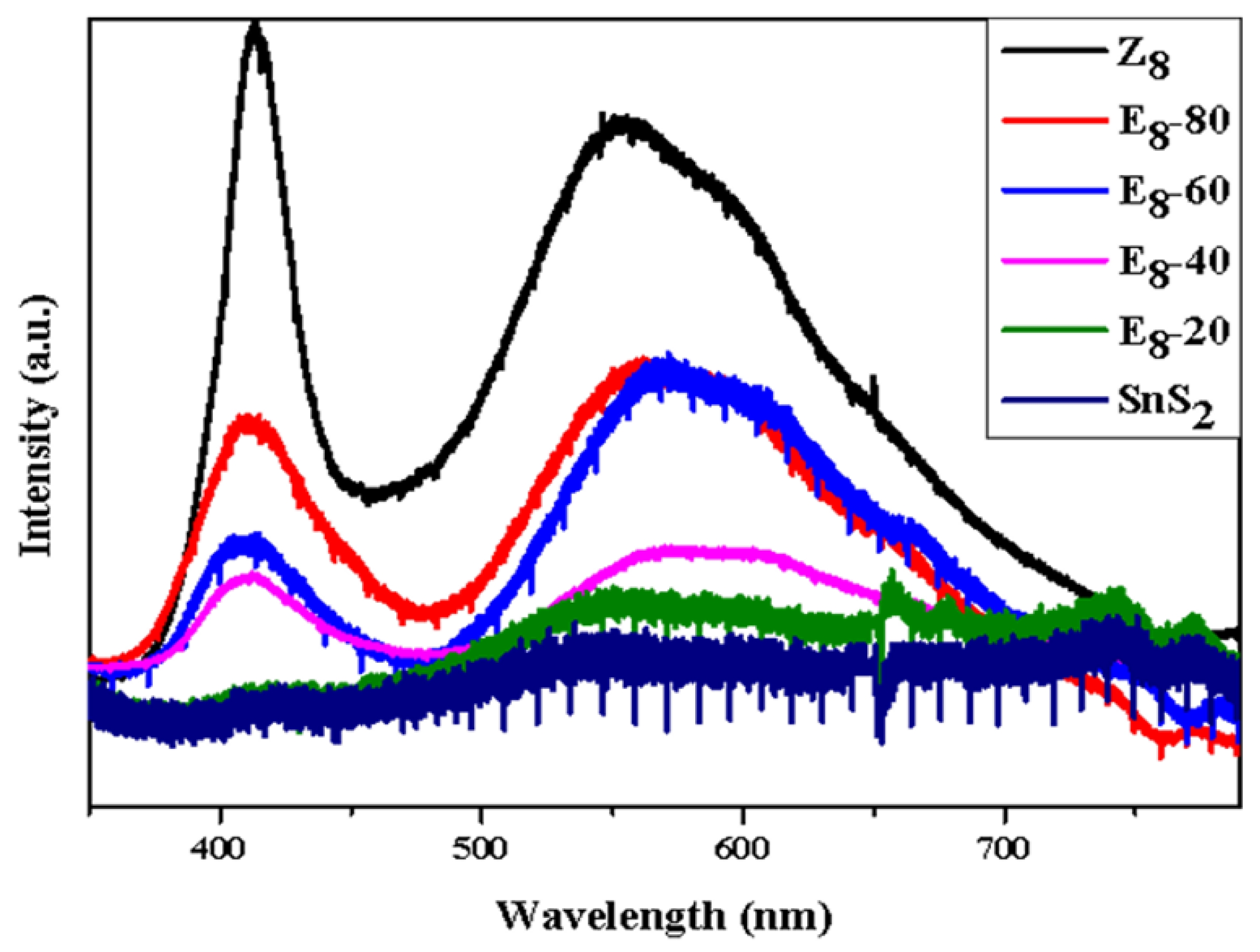

Fig. 5 shows the PL spectrum of the SnS2, Z8, and E8-series powder mixtures under light excitation. Pure SnS2 exhibited a minor peak at 549.7 nm, which corresponded to the near band edge emission of SnS2 [46]. Considering sample Z8, a strong UV emission peak around 405 nm was observed, corresponding to near-band edge emission. The PL intensity of sample Z8 was significantly higher than that of SnS₂. Another broad emission peak in the range of 500-650 nm corresponded to deep-level emission relating to structural defects in ZnO, such as oxygen vacancies (VO꙼̈), zinc vacancies (V"Zn), interstitial oxygen ion (O"i), and interstitial zinc ion (Zn) [47]. These defects trapped electrons that transitioned to the valence band, then released fluorescence in different wavelength ranges. Specifically, the green emission peak around 535 nm indicated VO꙼̈ to valence band emission. On the other hand, the yellow emission peak around 565 nm was due to electrons transitioning from the conduction band to the O"i energy level [46]. Peaks beyond 590 nm correspond to orange and red emission, indicating emissions from oxygen anti-sites (Ozn) or O"i. Furthermore, it was also observed that as the SnS2 content increased, both near band edge emission and deep level emission decreased due to the low emission intensity of SnS2. This decrease was attributed to the contact between SnS2 nanoparticles and flower-like ZnO crystals, which might lead to charge transfer near the hetero-interface.

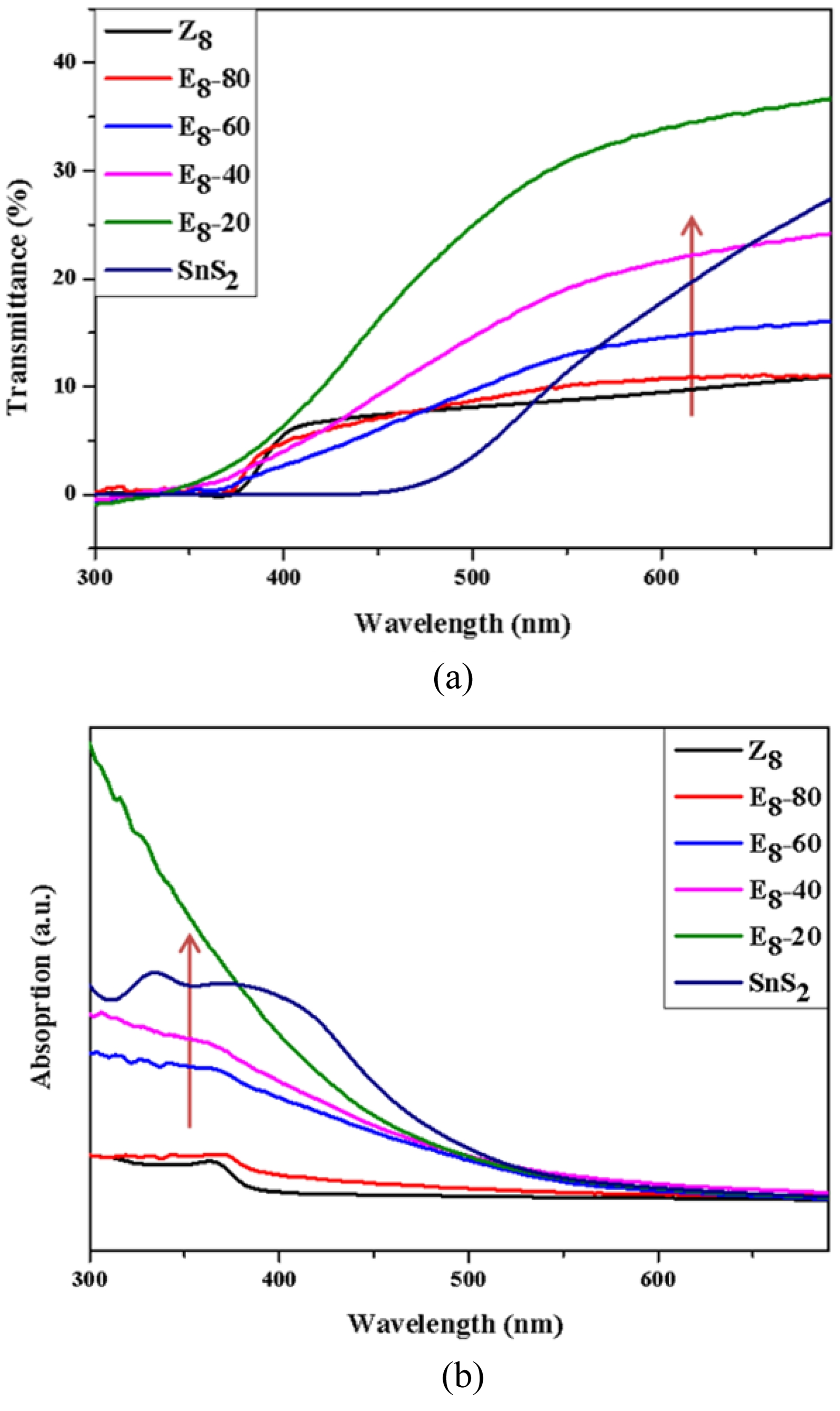

The UV-Vis spectrometer was used to analyze the optical properties of the powder mixtures. Fig. 6 shows the UV-Vis (a) transmission and (b) absorption spectra for SnS2, Z8, and the E8-series mixtures. It was observed that the absorption edge of SnS₂ and Z8 were approximately at 450 nm and 380 nm, respectively. The spectral features of the three samples, E8-40, E8-60, and E8-80, were intermediate between those of SnS2 and Z8, meanwhile the absorption edge of the mixtures gradually shifted toward the spectral characteristics of sample Z8. Notably, sample E8-20 exhibited superior UV light absorption in the wavelength range of 300-380 nm compared to all other samples. A shift in the light absorption band was observed in all nanocomposite powders, which may be related to the heterointerface formed by the contact between SnS2 nanoparticles and flower-like ZnO. As discussed in the XPS analysis from Fig. 4, the heterojunction can lead to changes in the overall Fermi level of the SnS2-ZnO nanocomposites. The increase in UV absorption intensity of sample E8-20 is likely related to the large interfacial area formed by 80 mol% SnS₂ and 20 mol% ZnO. These ZnO nanoparticles were amorphous as observed from the XRD pattern in Fig. 2 and may lead to the formation of a significant number of type-II SnS₂–ZnO band structures [48], resulting in enhanced charge transfer upon UV irradiation.

|

Fig. 1 TEM bright field images of (a) SnS2 and (b) Z8, showing particle sizes < 50 nm for SnS2 and > 1 μm for sample Z8. |

|

Fig. 2 XRD patterns of SnS2, Z8, and E8-series samples with a scanning rate of 3o/min. |

|

Fig. 3 Surface morphologies of E8-series samples: (a) E8-80, (b) E8-60, (c) E8-40, (d) E8-20. |

|

Fig. 4 Binding energy of (a) Sn 3d5/2 and Sn 3d3/2 orbitals and (b) Zn 2p3/2 and Zn 2p1/2 orbitals of E8-series samples. |

|

Fig. 5 The PL spectra of the SnS2, Z8, and E8-series powder mixtures including E8-20, E8-40, E8-60, E8-80. |

|

Fig. 6 (a) Transmittance and (b) absorption spectra of E8-series samples in the 300-700 nm range. |

By separately synthesizing SnS₂ and ZnO nanopowders, a simple and industrially feasible physical mixing method can be used to produce nanocomposite powders with high UV light absorption performance. Regarding their structural analysis, ZnO contained various defects that led to changes in the binding energy of Zn ions. The SnS2 nanoparticles extensively covered the ZnO crystals and probably formed a small number of SnS2-ZnO contact areas, leading to the shift of binding energies of cations. Although this contact condition did not cause a significant shift in the UV absorption band, the powder mixture with a molar ratio of 80/20 for the SnS₂-ZnO nanocomposite exhibited a higher UV absorption level than pure SnS₂ or ZnO. The major cause can be attributed to the charge transfer between the amorphous ZnO nanoparticles and the SnS2 nanocrystallites, thus enhancing UV light absorption performance in the sample E8-20. Additionally, the excellent antibacterial properties of SnS₂ make the SnS₂-ZnO nanocomposite developed in this study a promising coating material with strong UV absorption capability.

This research was funded by the National Science and Technology Council (NSTC), Taiwan [grant numbers NSTC 113-2221-E-167-009-].

- 1. K.J. Norton, F. Alam, and D.J. Lewis, Appl. Sci. 11[5] (2021) 2062.

-

- 2. G. Liu, Z. Li, T. Hasan, X. Chen, W. Zheng, W. Feng, D. Jia, Y. Zhou, and P. An, Hu, J. Mater. Chem. A 5 (2017) 1989-1995.

-

- 3. G. Su, V.G. Hadjiev, P.E. Loya, J. Zhang, S. Lei, S. Maharjan, P. Dong, P.M. Ajayan, J. Lou, and H. Peng, Nano Letters 15[1] (2015) 506-513.

-

- 4. F. Tan, S. Qu, X. Zeng, C. Zhang, M. Shi, Z. Wang, L. Jin, Y. Bi, J. Cao, Z. Wang, Y. Hou, F. Teng, and Z. Feng, Solid State Commun. 150[1] (2010) 58-61.

-

- 5. E. Liu, J. Chen, Y. Ma, J. Feng, J. Jia, J. Fan, and X. Hu, J. Colloid Interface Sci. 524[15] (2018) 313-324.

-

- 6. D. Mandal, J. Halder, P. De, A. Chowdhury, S. Biswas, and A. Chandra, ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 5[6] (2022) 7735-7747.

-

- 7. H. Zhao, H. Zeng, Y. Wu, W. Qi, S. Zhang, B. Li, and Y. Huang, Prog. Nat. Sci.: Mater. Int. 28[6] (2018) 676-682.

-

- 8. T. Waket, T. Sarakonsri, K.E. Aifantis, and S.A. Hackney, J. Ceram. Process. Res. 17[2] (2016) 73-79.

-

- 9. T. Shibata, T. Miura, T. Kishi, and T. Nagai, Journal of Crystal Growth 106[4] (1990) 593-604.

-

- 10. J. George and C.K.V. Kumari, J. Cryst. Growth 63[2] (1983) 233-238.

-

- 11. R. Schlaf, N.R. Armstrong, B.A. Parkinson, C. Pettenkofer, and W. Jaegermann, Surf. Sci. 385[1] (1997) 1-14.

-

- 12. A.Y. Jaber, S.N. Alamri, and M.S. Aida, J. Appl. Phys. 51 (2012) 065801.

-

- 13. V. Gadore, S.R. Mishra, K.K. Yadav, and M. Ahmaruzzaman, Sci. Rep. 14 (2024) 23493.

-

- 14. A. Fakhri and S. Behrouz, Sol. Energy 117 (2015) 187-191

-

- 15. R. Gaur and P. Jeevanandam, J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 18[1] (2018) 165-177.

-

- 16. C. Chen, B. Yu, P. Liu, J. Liu, and L. Wang, J. Ceram. Process. Res. 12[4] (2011) 420-425.

-

- 17. P. Jitti-a-pom, S. Suwanboon, P. Amornpitoksuk, and O. Patarapaiboolchai, 12[1] (2011) 85-89.

-

- 18. S. Suwanboon, P. Amornpitoksuk, and S. Muensit, J. Ceram. Process. Res. 11[4] (2010) 419-424.

-

- 19. A. Sedghi and N.R. Noori, J. Ceram. Process. Res. 12[6] (2011) 752-755.

-

- 20. M.J.F. Empizo, K. Yamanoi, K. Fukuda, R. Arita, Y. Minami, T. Shimizu, N. Sarukura, T. Fukuda, A.B. Santos-Putungan, and R.M. Vargas, J. Ceram. Process. Res. 16[1] (2015) 98-101.

-

- 21. F. Song, Y. Sun, and P. Rao, J. Ceram. Process. Res. 22[5] (2021) 521-526.

-

- 22. M. Ji and Y.-I. Lee, J. Ceram. Process. Res. 22[4] (2021) 386-393.

-

- 23. U. Özgür, Y.I. Alivov, C. Liu, A. Teke, M.A. Reshchikov, S. Doğan, V. Avrutin, S.-J. Cho, and H. Morkoç, J. Appl. Phys. 98 (2005) 041301.

-

- 24. A. Hezam, K. Namratha, Q.A. Drmosh, B.N. Chandrashekar, K.K. Sadasivuni, Z.H. Yamani, C. Cheng, and K. Byrappa, CrystEngComm, 19 (2017) 3299-3312.

-

- 25. S.H. Ko, D. Lee, H.W. Kang, K.H. Nam, J.Y. Yeo, S.J. Hong, C.P. Grigoropoulos, and H.J. Sung, Nano Lett. 11[2] (2011) 666-671.

-

- 26. E.M. Abdel-Fattah, S.M. Alshehri, S. Alotibi, M. Alyami, and D. Abdelhameed, Crystals 14[10] (2024) 892.

-

- 27. B.S.P. Govindaraj, A.M. Tripathi, S.S. Kushvaha, S. Swaminathan, R. Venkatesan, A. Jamespandi, and J. Mayandi, Zeitschrift fur Physikalische Chemie, 2024.

-

- 28. S.A. Thomas, J. Cherusseri, and D.N. Rajendran, ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 6[5] (2024) 3346-3361.

-

- 29. N. Parveen, S.A. Ansari, H.R. Alamri, M.O. Ansari, Z. Khan, and M.H. Cho, ACS Omega 3[2] (2018) 1581-1588.

-

- 30. Z. Bin and Y. Yin, J. Ceram. Process. Res. 18[2] (2017) 108-111.

-

- 31. J. Moghaddam and S. Mollaesmail, J. Ceram. Process. Res. 14[4] (2013) 459-462.

-

- 32. M.R. Vaezi, J. Ceram. Process. Res. 16[4] (2015) 418-421.

-

- 33. S. Suwanboon, P. Amornpitoksuk, P. Bangrak, A. Sukolrat, and N. Muensite, J. Ceram. Process. Res. 11[5] (2010) 547-551.

-

- 34. L.C. Nehru and C. Sanjeeviraj, J. Ceram. Process. Res. 14[6] (2013) 712-716.

-

- 35. I. Zgura, N. Preda, G. Socol, C. Ghica, D. Ghica, M. Enculescu, I. Negut, L. Nedelcu, L. Frunza, C.P. Ganea, and S. Frunza, Mater. Res. Bull. 99 (2018) 174-181.

-

- 36. O. Carp, A. Tirsoaga, R. Ene, A. Ianculescu, R.F. Negrea, P. Chesler, G. Ionita, and R. Birjega, Ultrason. Sonochem. 36 (2017) 326-335.

-

- 37. G. Fleer, M. Cohen Stuart, and F. Leermakers, “Fundamentals of Interface and Colloid Science” (Academic Press, 2005) p. 1.1-1.94.

-

- 38. J. Zhang, G. Huang, J. Zeng, X. Jiang, Y. Shi, S. Lin, X. Chen, H. Wang, Z. Kong, J. Xi, and Z. Ji, J. Alloys Compd. 775 (2019) 726-735.

-

- 39. H. Li, B. Zhang, X. Wang, J. Zhang, T. An, Z. Ding, W. Yu, and H. Tong, Front. Chem. 7 (2019) 339.

-

- 40. V.P. Singh and C. Rath, RSC Adv. 5[55] (2015) 44390-44397.

-

- 41. M. Sultan, S. Mumtaz, A. Ali, M.Y. Khan, and T. Iqbal, Superlattices Microstruct. 112 (2017) 210-217.

-

- 42. S. Wang, B. Zhu, M. Liu, L. Zhang, J. Yu, and M. Zhou, Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 243 (2019) 19-26.

-

- 43. W. Yu, D. Xu, and T. Peng, J. Mater. Chem. A 3[39] (2015) 19936-19947.

-

- 44. M. Willander, O. Nur, Q.X. Zhao, L.L. Yang, M. Lorenz, B.Q. Cao, J. Zuniga Perez, C. Czekalla, G. Zimmermann, and M. Grundmann, Nanotechnology 20[33] (2009) 332001.

-

- 45. A. Kołodziejczak-Radzimska and T. Jesionowski, Materials 7[4] (2014) 2833-2881.

-

- 46. K.M. Kim, B.S. Kwak, S. Kang, and M. Kang, Int. J. Photoenergy, (2014) 479508.

-

- 47. M.D. McCluskey, “1 - Defects in ZnO, in Defects in Advanced Electronic Materials and Novel Low Dimensional Structures”, (Woodhead Publishing, 2018) p. 1-25.

-

- 48. T.T. Salunkhe, V. Kumar, A.N. Kadam, M. Mali, and M. Misra, Ceram. Int. 50[1] (2024) 1826-1835.

-

This Article

This Article

-

2025; 26(6): 1074-1080

Published on Dec 31, 2025

- 10.36410/jcpr.2025.26.6.1074

- Received on Jan 27, 2025

- Revised on Apr 22, 2025

- Accepted on Apr 28, 2025

Services

Services

- Abstract

introduction

experimental

results and discussion

conclusions

- Acknowledgements

- References

- Full Text PDF

Shared

Correspondence to

Correspondence to

- Alex C.H. Lee b and Horng-Hwa Lu b

-

aDepartment of Materials Science and Engineering, National Cheng Kung University, Tainan 70101, Taiwan, R.O.C.

bDepartment of Mechanical Engineering, National Chin-Yi University of Technology, Taichung 411030, Taiwan, R.O.C.

Tel : +886-4-23924504 ext 7152 (Alex C.H. Lee, ORCID: 0000-0002-0251-0931)

Tel : +886-4-23924504 ext 7179 (Horng-Hwa Lu) - E-mail: alexchlee@ncut.edu.tw (Alex C.H. Lee), hhlu@ncut.e

Copyright 2019 International Orgranization for Ceramic Processing. All rights reserved.

Copyright 2019 International Orgranization for Ceramic Processing. All rights reserved.