- Direct ink writing of magnesium orthosilicate bioceramic 3D scaffolds

Zong Qi Wonga, Wei Hong Yeoa,*, Jing Yuen Teya, Chen Hunt Tinga, Chui Kim Ngc, Ming Chian Yewd, Chee Hong Lawa, Jia Huey Simb, J. Purbolaksonoe and S. Rameshe

aDepartment of Mechanical and Materials Engineering, Lee Kong Chian Faculty of Engineering and Science, Universiti Tunku Abdul Rahman, 43000 Kajang, Selangor, Malaysia

bDepartment of Chemical Engineering, Lee Kong Chian Faculty of Engineering and Science, Universiti Tunku Abdul Rahman, Kajang 43000, Selangor, Malaysia

cCentre for Advanced Materials, Department of Manufacturing Technology, Faculty of Engineering & Technology, Tunku Abdul Rahman University of Management and Technology, 53300, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

dDepartment of Mechanical Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, Universiti Teknologi Petronas, 32610 Seri Iskandar, Perak, Malaysia

eDepartment of Mechanical Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, Universiti Malaya, Kuala Lumpur 50603, MalaysiaThis article is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Magnesium orthosilicate (Mg₂SiO₄), whose chemical name known as forsterite is a promising Mg-based bioceramic for orthopedic applications due to its bioactivity and superior mechanical properties. In this study, the magnesium orthosilicate powder was synthesized via a solid-state reaction using MgO and SiO₂. Subsequently, the printable ink was prepared using 40 vol% magnesium orthosilicate powder along with ammonium polyacrylate (BYK-154) as dispersant, hydroxypropyl methylcellulose (HPMC) as binder, and polyethylenimine (PEI) as flocculant. The ink mixture exhibited shear-thinning behaviour, suitable rheological behavior for extrusion and good printability. After printing, the printed 3D scaffold was then sintered at 1500 °C to obtain a magnesium orthosilicate structure with total porosity of 47.40%. Mechanical testing demonstrated a compressive strength of 14.61 MPa and a Young's modulus of 904.37 MPa, which fall within the range of mechanical properties of cancellous bone. These findings highlight the potential of direct ink writing (DIW) of magnesium orthosilicate as an orthopedic biomaterial.

Keywords: Direct ink writing, 3D printing, Magnesium orthosilicate, Forsterite, Bioceramics.

Magnesium (Mg) is recognized as a crucial element in the bone marrow microenvironment, where it supports bone development, mineralization, and the overall process of bone regeneration by influencing both osteoblast and bone marrow stem cell activity [1-3]. This intrinsic bioactivity, combined with favorable biodegradability, makes Mg-based bioceramics strong candidates for orthopaedic applications—particularly for materials that need to support new bone formation and gradually integrate with host tissue [2, 4].

Among the various Mg-based bioceramics, magnesium orthosilicate (forsterite, Mg₂SiO₄) stands out for its exceptional mechanical properties, including higher hardness and fracture toughness, which helps address the challenges of load-bearing implant applications. Magnesium orthosilicate also demonstrates high biocompatibility, effectively promoting cell attachment, proliferation, and differentiation, further supporting its use in bone tissue engineering [5]. However, secondary phases such as enstatite and periclase were occasionally formed during the synthesis of magnesium orthosilicate, which can adversely affect the mechanical properties of the structure [5-8]. Sara Lee et al. [6] have successfully synthesize magnesium orthosilicate through conventional sintering at temperature above 1300 °C without prior heat treatment. They have reported significant improvement in mechanical performance of the solid sintered samples, achieving a Vickers hardness of 7.68 GPa and fracture toughness of 5.15 MPa·m1/2 at 1500 °C. In addition, Ramesh et al. [7] investigated the influence of different sintering profiles on the densification and mechanical performance of magnesium orthosilicate ceramics synthesized through mechanical activation. They revealed that a minimum ball-milling time of 7 hours and sintering at 1400 °C were required to obtain single phase magnesium orthosilicate. These findings emphasized that optimizing the sintering process through controlled multi-step sintering profiles can significantly enhance microstructural uniformity while minimizing defects that compromise mechanical strength.

While calcium-based bioceramics such as hydroxyapatite and tricalcium phosphate have been widely studied and used clinically, their inherent brittleness and limited mechanical strength constrain their application in load-bearing implants [5]. In contrast, Mg-based bioceramics such as magnesium orthosilicate combine bioactivity with enhanced mechanical performance, offering a more balanced profile for orthopaedic use [1-5, 9]. Despite these advantages, the development and application of Mg-based ceramics, especially through advanced techniques like 3D printing, remain relatively underexplored [10]. Conventional fabrication methods for bioceramics scaffolds, such as sol-gel synthesis, solid-state reactions, and template-based approaches, typically struggle to provide precise control over macro-porosity. These approaches often yield scaffolds with irregular pore structures, poorly interconnected and inconsistent porosity throughout the structure, making it challenging to tailor the mechanical properties of bioceramics scaffolds to desired values.

Direct ink writing (DIW), an extrusion-based 3D printing technique, overcomes these challenges by enabling precise control over scaffold architecture, including macro-porosity, shape, and interconnectivity. DIW facilitates the fabrication of scaffolds with tailored mechanical and biological properties, enhancing their suitability for bone repair. Recent advances in DIW have enabled the production of bioceramics scaffolds with uniform microporous and customizable structures. These scaffolds not only support bone regeneration but also provide the mechanical stability required for load-bearing applications. For example, Somers et al. [11] synthesized the doped β-tricalcium phosphate (β-TCP) bioceramic ink to 3D print the macro-porous scaffolds. DIW slurries were formulated with the use of 42 vol% of powder in dispersed aqueous solution containing carboxymethylcellulose and polyethyleneimine mixture to obtain the printable ink. The sintered structures showed improvement in densities and compressive strengths as compared to undoped β-TCP. Dai et al. [12] produced porous silicon nitride (Si3N4) ceramics with varied macropore structures by direct ink writing. They have successfully fabricated a series of porous Si3N4 bioceramics with different macropore sizes by varying the printing parameters. The resulting porous bioceramics exhibited relative densities ranging from 45.72% to 82.99% and flexural strengths from 79.8 MPa to 492.6 MPa. Their results indicated the strength of parallelogram pores is ~32% higher than squares and ~45% higher than triangles, which was consistent with the predicted changes through calculation. Wu et al. [13] investigated the effect of varying manganese doping on the strontium magnesium silicate (Ca2MgSi2O7) porous 3D-printed scaffolds for bone defect repair. Their results demonstrated that sintered doped scaffolds possess excellent mechanical properties, biodegradability and biocompatibility.

On the other hand, Tonelli et al. [8] investigated the feasibility of 3D printing MgO-SiO₂ cement paste to produce Mg-based bioceramics using materials extrusion techniques (a.k.a DIW). Although their results revealed that the sintered scaffold structure primarily consisted of magnesium orthosilicate and clinoenstatite; however, some samples were ruptured after calcined at 1000 oC. To address this issue, the present study aims to develop a magnesium orthosilicate ceramic feedstock for DIW ensuring printability and structural fidelity. The formulation is design to capable of producing crack-free 3D-printed structures. Furthermore, the sintered scaffolds were characterized for their microstructure, phase composition, density, porosity, and mechanical properties such as compressive strength, Young’s modulus to evaluate their potential in bone tissue engineering applications.

Synthesis of magnesium orthosilicate powder

Magnesium oxide (MgO) (99.5%, Macklin, Shanghai, China) and hydrophilic fumed silica (HF-SiO2) (99.5%, Aladdin Scientific, Shanghai, China) were mixed in deionised (DI) water with 2:1 molar ratio to achieve the stoichiometric composition based on Eq. (1) to form magnesium orthosilicate (Mg2SiO4) [8, 14]. The mixture was homogenized using a high-shear mixer for 2 hours, dried in over for 24 hours at 90 °C and calcined at 1200 °C for 3 hours. The resulting magnesium orthosilicate powder was crushed and sieved through a 500 µm metal mesh.

Ink preparation

Magnesium orthosilicate powder (40 vol%) was dispersed in DI water with ammonium polyacrylate BYK-154 (6.0 wt%, based on powder weight) and mixed at 2000 rpm for 2 min using a planetary centrifugal mixer. Then, 0.2 wt% hydroxypropyl methylcellulose (HPMC) was added and mixed again under the same conditions. The ink was rested for 1 hour to allow cellulose chain relaxation. Finally, 0.2 wt% polyethylenimine (PEI) was added as a flocculant, and the mixture was repeatedly mixed at 2000 rpm for 2 min until a homogeneous ink was obtained.

Rheological characterization

Rheological properties were analyzed using a rotational rheometer (Physica MCR 301, Anton Paar) with a 25 mm parallel plate with a 1.0 mm gap between the plates. Three tests were conducted: flow sweep, amplitude sweep, and three-interval thixotropy test (3ITT). Viscosity was measured over a shear rate, γ̀ range of 0.01 s⁻¹ to 100 s⁻¹. The amplitude sweep test was performed by measuring the storage modulus (G′) and loss modulus (G′′) at frequency of 1 Hz with controlled shear stress, τ of 1 to 1000 Pa. 3ITT was conducted to measure the thixotropy response at frequency of 1 Hz based on (i) τ of 10 Pa for 120 s; (ii) t of 300 Pa for 120 s; (iii) τ of 10 Pa for 300 s.

Printing

An in-house customized 3D printer with motor driven extruder was used to produce a 20 × 20 × 20 mm thin-wall cube and scaffold structure. Printing was performed with a layer height, h =0.7 mm and a width, d = 1.2 mm. The printing speed test was carried out in the range of 3 - 8 mm/s to investigate the ideal setting. Then, the green body was dry at room temperature for at least 24 hr.

Sintering

The green body was heated in a muffle furnace (SIC8-1600, Control Therm) to 1500 ℃ with a heating rate of 5 ℃/min and held for 2 hours.

Characterization and mechanical testing

X-ray Diffraction (XRD) was performed on the calcined magnesium orthosilicate powder and the sintered magnesium orthosilicate samples from a scanning angle, 2θ of 10 º to 60 º using a step size of 0.02º. Besides, the density of the sintered body was measured using the Archimedes’ immersion method (JIS R 1634) [15] with the Eq. (2) below,

were ρb is the bulk density of the sintered body, ρL is the bulk density of the immersion liquid, m1 is the mass of dry test specimen, m2is the apparent mass of the immersed test specimen, m3is the mass of the soaked test specimen. Next, microstructures of both surface and cross-section area of the scaffold were observed via scanning electron microscopy (SEM, Hitachi S-4300N). Lastly, uniaxial compression tests were performed on the scaffolds using a universal testing machine (Shimadzu AGS-100kNX, 100 kN) at a loading rate of 0.5 mm/min until failure of the structure.

Rheology and printability

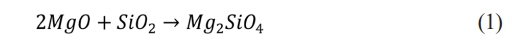

The flow sweep test (Fig. 1(a)) confirmed the feedstock exhibited non-Newtonian shear-thinning behaviour, with a flow index, n = 0.28, yield stress, τy = 14 Pa, consistency index, K = 282 Pa∙sn and high correlation coefficient, R2 = 0.94 obtained from the Herschel-Bulkley model as in Eq. (3) [16-18]:

where η is viscosity, and γ̀ can be associated to the printing speed and nozzle diameter through Eq. (4) as shown below [19]:

where Q̇ is the volumetric flow rate, and r is the nozzle radius. The calculated γ̀ of 40.64 s⁻¹ at Q̇ of 4.20 mm³/s resulted in a printable ink viscosity of 19.91 Pa·s and estimated a printing τ = 809 Pa. These results indicate suitable properties for DIW, with a relatively low viscosity in the range of 10 to 100 Pa·s, ensuring smooth extrusion [19, 20].

The amplitude sweep test (Fig. 1(b)) identified the viscoelastic range, with a τy of 32 Pa where the G′ and G′′ remain independent from thet. The flow stress (τf was observed at the point of G′ cross over the G′′ at 102 Pa, marking the transition from a solid-like to a liquid-like state due to the structural breakdown of ink [21-24]. It falls within the printable range of 10 Pa to 1.5 kPa, confirming printability [24].

The 3ITT test (Fig. 1(c)) showed the feedstock exhibited solid-like behaviour (G' > G'') at the first interval, transitioned to a liquid-like state (G'' > G') under higher τ at the second interval and recovered its solid -like state (G' > G'') upon returning to a lowert at the third interval which indicated the structure recovery of the ink. Although the full recovery of the G' was slow, the immediate recovery of is G' at 4.0 kPa was found to be sufficient to support the structural integrity during printing. This is supported by Fig. 1(d), which demonstrates successful printing of thin-wall and scaffold structures without collapse. These results are consistent with previous research findings, which indicate that sufficient G' is key to ensuring structural fidelity even when the ink does not fully recover to its initial G' after instantaneous shear [25-27].

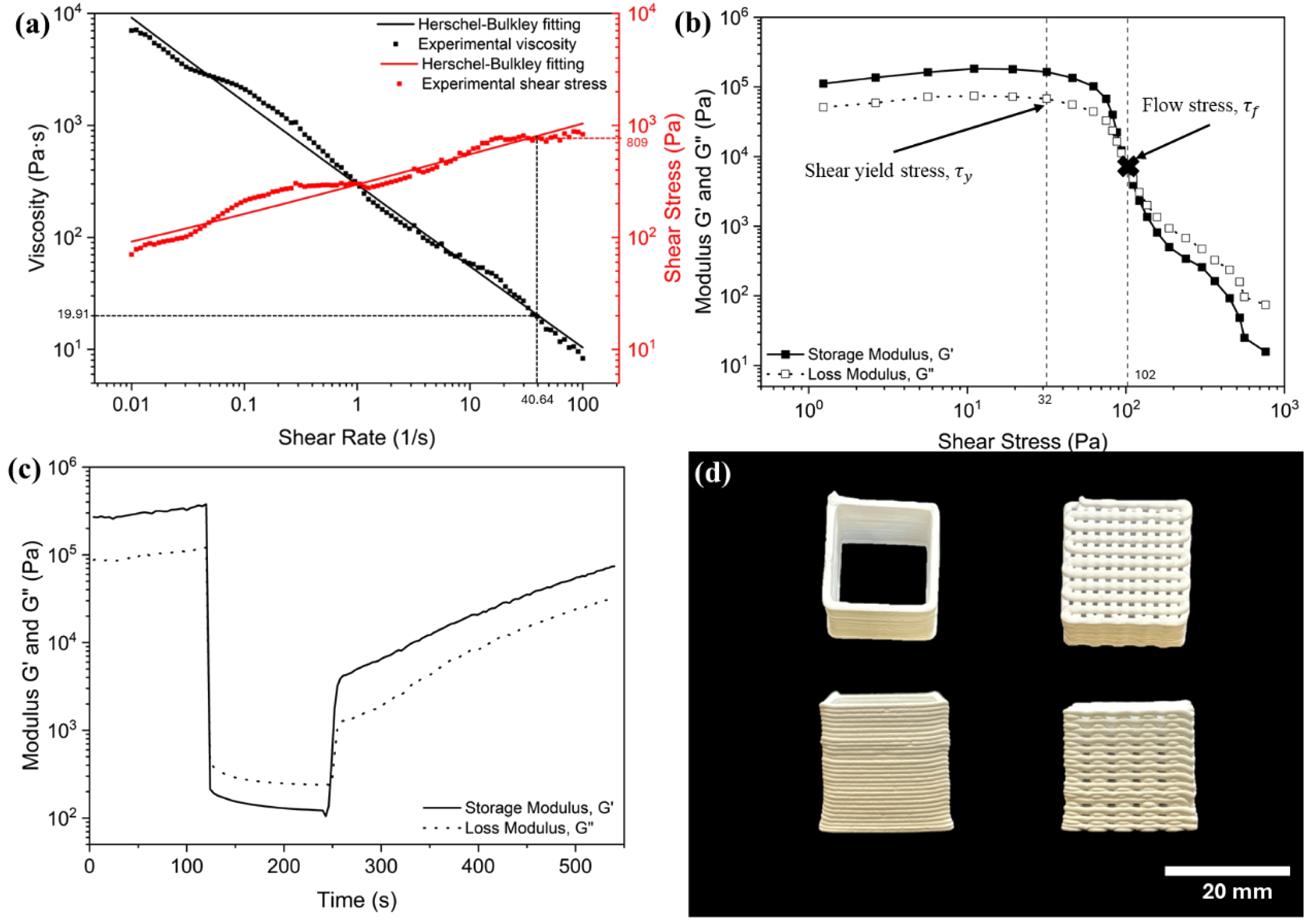

To perform the printability study, the printing speed of 3-8 mm/s were conducted and results were shown in Fig. 2. At a slow printing speed of 3 mm/s, the structure is under-extruded, resulting in discontinuous ink layers with voids. Conversely, when the printing speed is increased to 8 mm/s, the ink becomes severely over-extruded and causing the structure distorted. An optimal print was achieved by setting the printing speed to 5 mm/s. At this speed, the resulting thin-wall structure stacked up well without collapsing or exhibiting under- or over-extrusion issues.

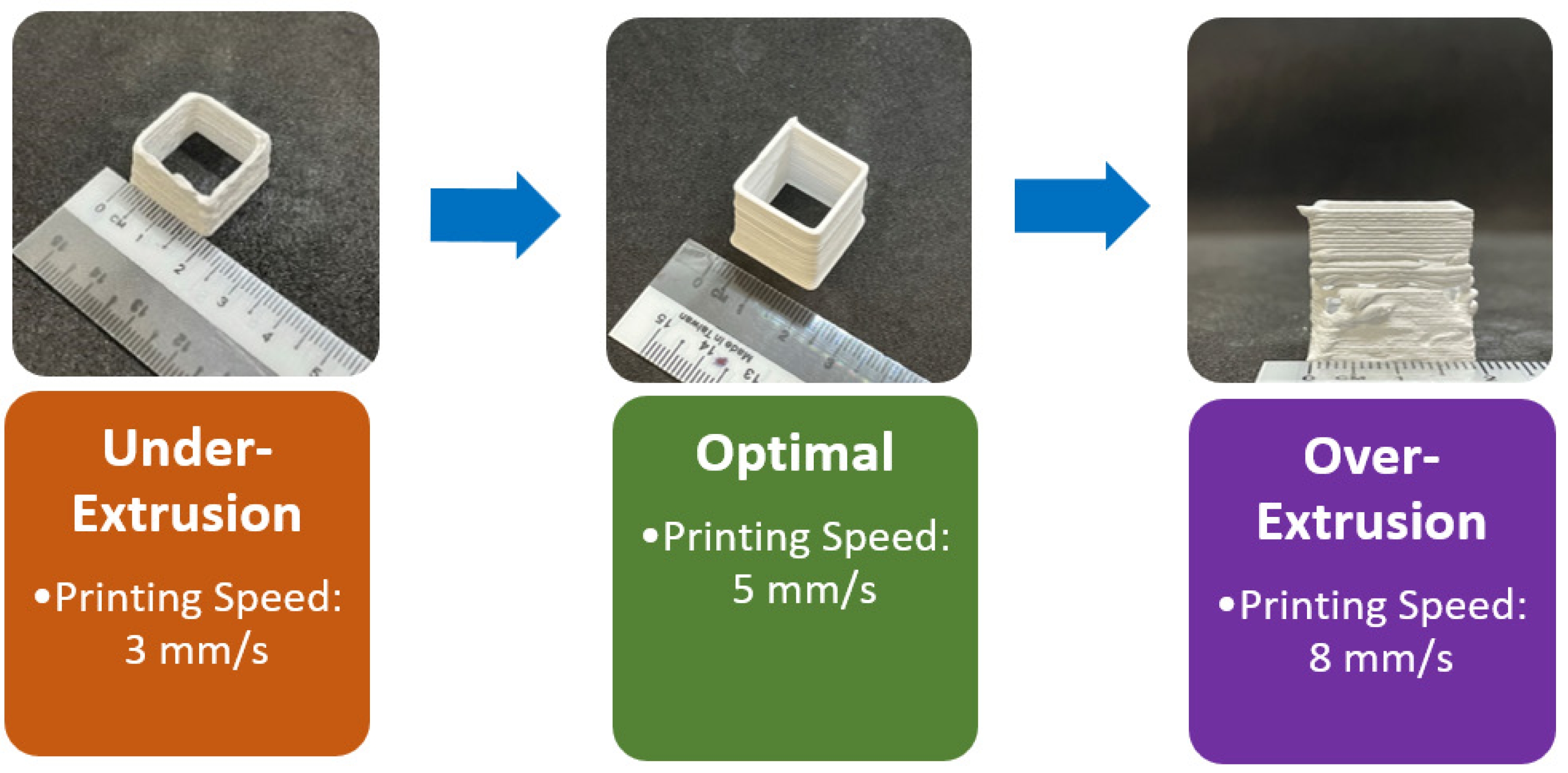

Thus, a printing speed of 5 mm/s, a layer height of 0.7 mm, and a layer width of 1.2 mm were identified as the optimal printing parameters for the magnesium orthosilicate feedstock with 40 vol% solid loading. These parameters, combined with the high storage modulus of over 105 Pa, enable the layers to stack up without deflection or sagging. These parameters were subsequently used in the printing of thin-wall cube, scaffold, and solid square structures with different batches of ink as shown in Fig. 3.

Characterization of 3D-Printed Magnesium orthosilicate Scaffolds

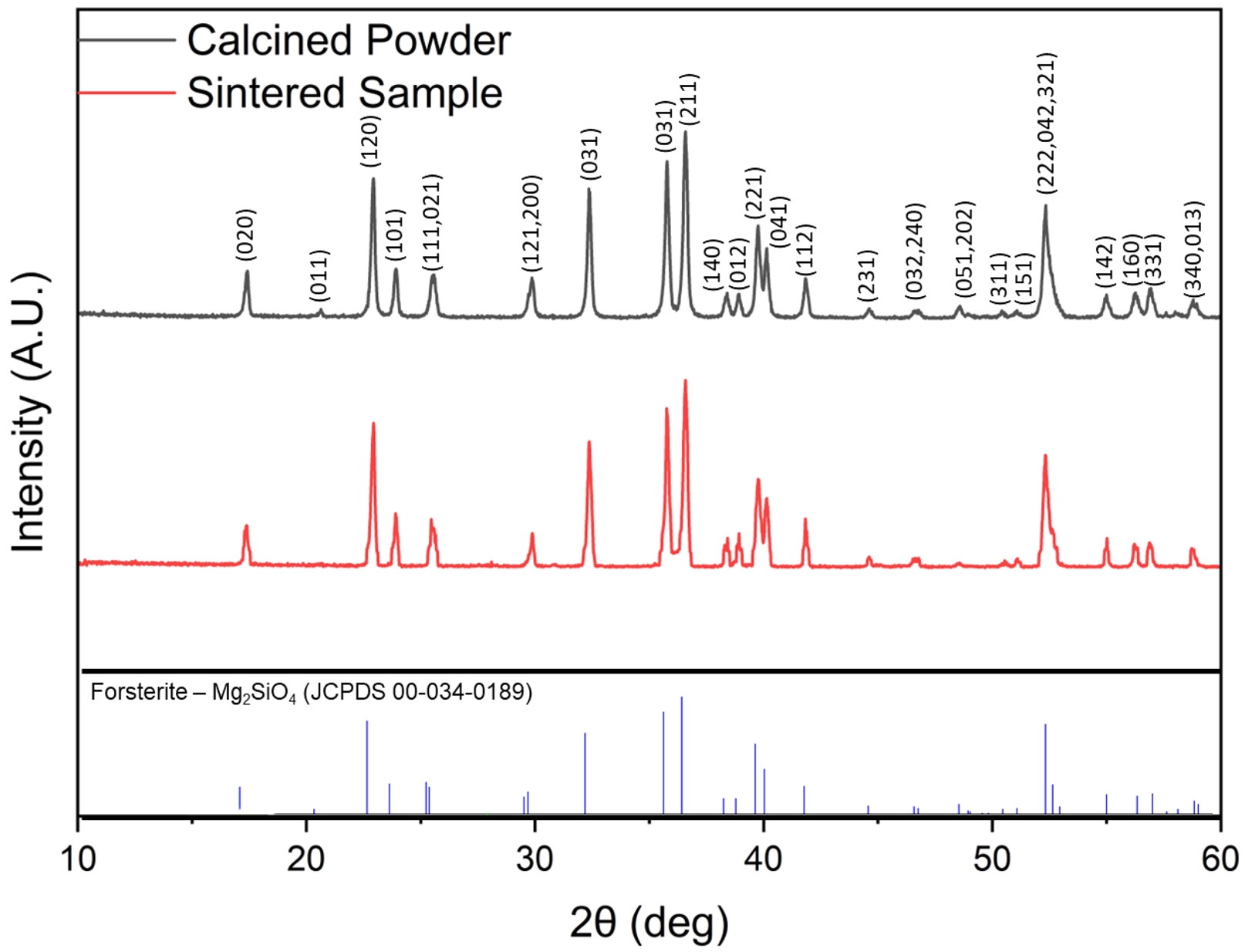

XRD analysis of the synthesized magnesium orthosilicate powder (Fig. 4) showed sharp, well-defined peaks, confirming high crystallinity. The diffraction pattern matched Joint Committee on Powder Diffraction Standards (JCPDS) card #34-0189, confirming the successful synthesis of pure magnesium orthosilicate (Mg2SiO4) without impurities such as enstatite or silica. As for the sintered 3D-printed structures, the XRD patterns remained consistent with those of the standard JCPDS #34-0189 for magnesium orthosilicate. The sintered samples exhibited no detectable peaks associated with impurity phases, mirroring the purity observed in the initial powder. This result also confirmed that the sintering and printing processes did not induce any phase transformation or decomposition, and the printed constructs retained the desired magnesium orthosilicate phase throughout processing. This is important because magnesium orthosilicate is known for its superior mechanical stability and low degradation rate when immersed in simulated body fluid (SBF). This stability is crucial for long-term viability, as the material's slow degradation allows the structure to remain intact while concurrently supporting biomineralization [9].

In terms of densification, the sintered scaffold filaments showed an average of 2.69 ± 0.01 g/cm³, corresponding to a relative density (rRe of 83.51% relative to magnesium orthosilicate’s theoretical density (3.221 g/cm³) [28].

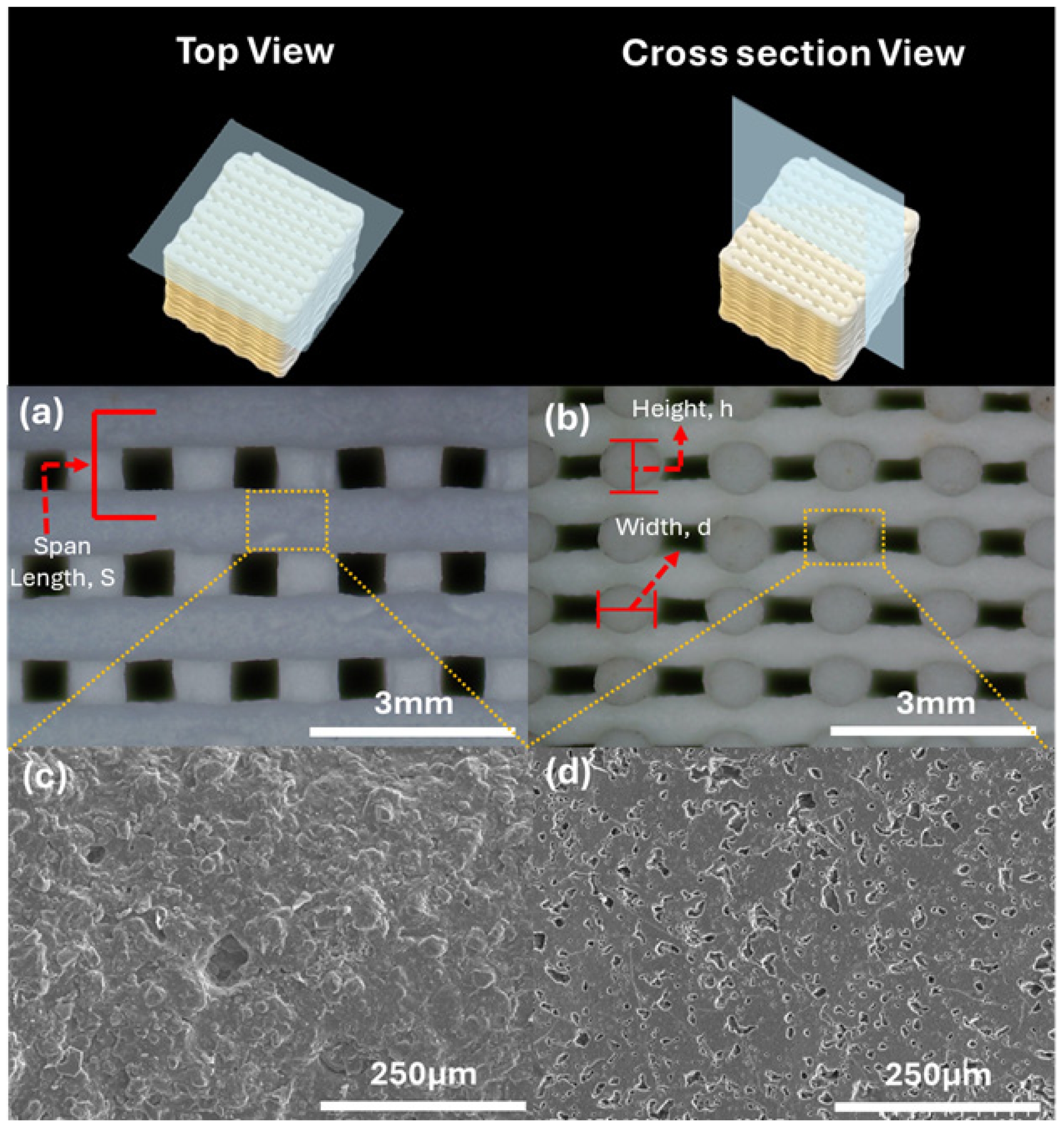

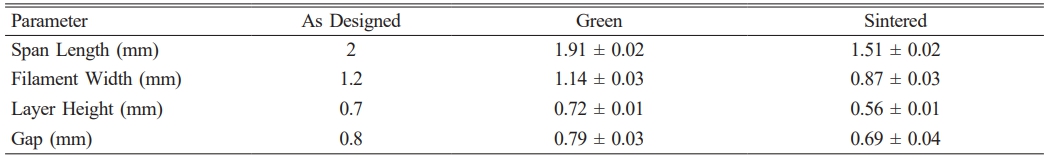

Fig. 5 shows the SEM images of porous structure in individual rods, with multiscale porosity on filament surfaces and cross-sections without cracking. The filaments retained adhesion points, indicating good shape retention. Table 1 shows the dimensional changes of 3D printed and sintered scaffold structures that were measured using optical microscope. The average linear shrinkage of the scaffold structure, which was determined using vernier caliper, was recorded as 19.96 ± 0.95%. The porosity of the sintered structure can be determined based on the measurement and Eq. (5) and Eq. (6) below [29-31]:

where pM is the macro porosity of the scaffold and pm is the micro porosity in filament. Generally, the sample exhibited a pm of 17.97%, pM of 29.43%, and total porosity of 47.40%. In addition, the gap distance and overall porosity measured in the sintered scaffold were in close agreement with the theoretical criteria considered favourable for bone regeneration, which pore sizes in the range of 50-1000 µm and porosity levels between 30% and 90% [32, 33]. Meeting these structural requirements is crucial, as sufficient pore size facilitates cell migration, vascularization, and nutrient transport, while adequate porosity ensures space for new bone tissue ingrowth without compromising mechanical stability. Increased surface roughness and homogeneously distributed micropores were also observed in SEM micrographs in Fig. 5(c) and 5(d).

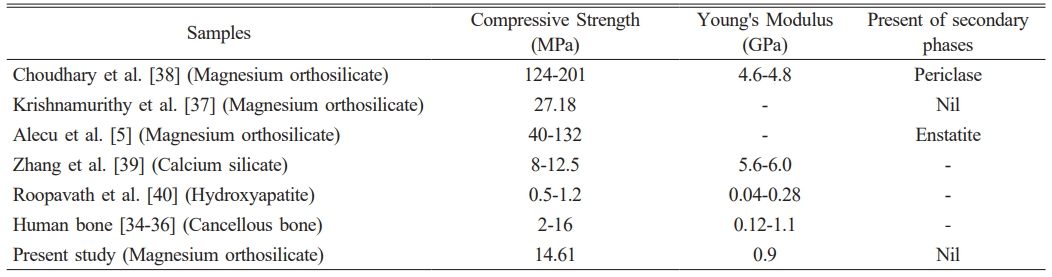

In terms of the mechanical properties, the scaffold structure exhibited a compressive strength of 14.61 ± 2.22 MPa and a Young’s modulus of 904.37 ± 112.23 MPa, both within the ranges of human cancellous bone (2-16 MPa and 0.12-1.1 GPa, respectively) [34-36]. Compared to literature values for magnesium orthosilicate scaffolds fabricated by conventional methods [5, 37, 38], the compressive strength of the 3D-printed structure in present study is generally lower than the values reported by Krishnamurithy et al. [37] (27.18 MPa), Alecu et al. [5] (40-132 MPa) and Choudhary et al. [38] (124-201 MPa) as in Table 2. Meanwhile, the Young’s modulus closely matches that of cancellous bone and lower than the 4.6-4.8 GPa range observed by Choudhary et al. [38]. When compared with other widely studied bioceramics such as calcium silicate and hydroxyapatite, the compressive strength of the 3D-printed structure in the present study is higher than that of calcium silicate reported by Zhang et al. [39] (8-12.5 MPa) and hydroxyapatite reported by Roopavath et al. [40] (0.5-1.2). On the other hand, the Young’s modulus of calcium silicate (5.6-6.0 GPa) is much higher than that of the present study and human cancellous bone, whereas hydroxyapatite shows lower results (0.04-0.28 GPa) compared to present study and fall within the lower range of human cancellous bone. The use of 3D printing as a fabrication method distinctly sets this work apart, allowing for precise control of the scaffold’s pore architecture and overall structural uniformity. By leveraging 3D printing, this study achieves a scaffold with sufficient compressive strength and modulus to support functional integration within bone. These findings demonstrate a successful approach to 3D printing and processing magnesium orthosilicate ceramic structures, contributing to advancements in bone tissue engineering.

|

Fig. 1 Rheology results of formulated ink: (a) viscosity and shear stress vs shear rate fitted with Herschel Bulkley model (b) amplitude sweep curve (c) 3ITT result (d) single wall and scaffold structure printed using formulated ink. |

|

Fig. 2 Printability results. |

|

Fig. 3 Printed specimens: (a) thin wall, (b) scaffold and (c) solid square samples. |

|

Fig. 4 XRD pattern of calcinated powder and sintered samples. |

|

Fig. 5 Microstructure of sintered scaffold structures. Optical images of (a) Top view and (b) cross section view, SEM images of (c) filament surface ×200 magnification, (d) filament cross section ×200 magnification. |

This study successfully formulated and 3D printed magnesium orthosilicate bioceramic using direct ink

writing with a 40 vol% of forsterite powder and additives such as BYK-154, HPMC, and PEI. Rheological analysis confirmed the ink's shear-thinning behaviour, viscoelasticity, and rapid structural recovery, ensuring its suitability for extrusion-based printing. The printed structures exhibited good shape retention and mechanical strength, while XRD analysis confirmed the formation of pure magnesium orthosilicate without secondary phases. Sintered scaffolds at 1500 ºC achieved

a filament with relative density of 83.51% and a total porosity of 47.70%. Additionally, the scaffold demonstrated a compressive strength of 14.61 MPa and a Young’s modulus of 904.37 MPa, which are within the properties of human cancellous bone. This work represents a significant advancement in the 3D printing of Mg-based bioceramics, offering a potential method for producing mechanically robust scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. Future research should focus on optimizing porosity, enhancing mechanical properties, and conducting in vivo biocompatibility assessments to establish magnesium orthosilicate as a viable material for orthopedic applications.

This work was supported by Fundamental Research Grant Scheme (FRGS) Grant No. FRGS/1/2022/TK10/UTAR/02/16 from Ministry of Higher Education, Malaysia.

- 1. L. Liu, P. Luo, P. Wen, and P. Xu, Front. Endocrinol. 15 (2024) 1406248.

-

- 2. Y. Zhu, J. Su, T. Qi, G. Zhang, P. Liu, H. Qin, Q. Yang, S. Yao, Y. Zheng, J. Weng, H. Zeng, and F. Yu, Biomater. Transl. 6[2] (2025) 114-126.

-

- 3. M. Tao, Y. Cui, S. Sun, Y. Zhang, J. Ge, W. Yin, P. Li, and Y. Wang, Mater. Today Bio. 31 (2025) 101635.

-

- 4. L. Qi, T. Zhao, J. Yan, W. Ge, W. Jiang, J. Wang, M. Gholipourmalekabadi, K. Lin, X. Wang, and L. Zhang, Biomater. Transl. 5[1] (2024) 3-20.

-

- 5. A.E. Alecu, G.C. Balaceanu, A.I. Nicoara, I.A. Neacsu, and C. Busuioc, Materials. 15[19] (2022) 6942.

-

- 6. K.Y. Sara Lee, K.M. Christopher Chin, S. Ramesh, J. Purbolaksono, M.A. Hassan, M. Hamdi, and W.D. Teng, J. Ceram. Process. Res. 14[1] (2013) 131-133.

-

- 7. S. Ramesh, S.S. Tan, L.T. Bang, C.Y. Tan, J. Purbolaksono, and W.D. Teng, J. Ceram. Process. Res. 16[6] (2015) 722-728.

-

- 8. M. Tonelli, A. Faralli, F. Ridi, and M. Bonini, J. Colloid Interface Sci. 598 (2021) 24-35.

-

- 9. S.K. Venkatraman, R. Choudhary, N. Vijayakumar, G. Krishnamurithy, H.R.B. Raghavendran, M.R. Murali, T. Kamarul, A. Suresh, J. Abraham, and S. Swamiappan, J. Mater. Res. 37 (2022) 608-621.

-

- 10. J. Dong, Y. Li, P. Lin, M.A. Leeflang, S. van Asperen, K. Yu, N. Tümer, B. Norder, A.A. Zadpoor, and J. Zhou, Acta Biomater. 114 (2020) 497-514.

-

- 11. N. Somers, F. Jean, M. Lasgorceix, N. Preux, C. Delmotte, L. Boilet, F. Petit, and A. Leriche, J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 43[2] (2023) 629-638.

-

- 12. Y.L. Dai, D.X. Yao, Y.F. Xia, M. Zhu, J. Zhao, F. Wang, and Y.P. Zeng, Ceram. Int. 50[23] (2024) 49033-49040.

-

- 13. R. Wu, L. Zhou, Y. Gao, Z. Xu, D. Chen, Z. Chen, T. Lin, D. Wu, K. Wang, Z. Wang, J. Lin, and W. Liu, Ceram. Int. 51[19] (2025) 28646-28664.

-

- 14. H. Liu, C. Jie, Y. Ma, Z. Wang, and X. Wang, Trans. Indian Ceram. Soc. 79[2] (2020) 83-87.

-

- 15. Japanese Industrial Standards Committee (JISC), in “Test methods for density and apparent porosity of fine ceramics (JIS R1634)” (Japanese Standards Association, 1998).

- 16. H.A. Barnes, J.F. Hutton, and K. Walters, in “An Introduction to Rheology: Rheology Series” (Elsevier, 1989) p. 11.

-

- 17. W.H. Herschel, and R. Bulkley, Kolloid-Z. 39 (1926) 291-300.

-

- 18. X. Ang, J.Y. Tey, and W.H. Yeo, Appl. Mater. Today. 38 (2024) 102174.

-

- 19. X. Ang, J.Y. Tey, W.H. Yeo, and K.P.Y. Shak, J. Manuf. Process. 90 (2023) 28-42.

-

- 20. Q. Liu, and W. Zhai, ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 14[28] (2022) 32196-32205.

-

- 21. A. Schwab, R. Levato, M. D’Este, S. Piluso, D. Eglin, and J. Malda, Chem. Rev. 120[19] (2020) 11028-11055.

-

- 22. S.W.Z. Fong, J.Y. Tey, W.H. Yeo, and S.F. Tee, J. Manuf. Process. 132 (2024) 519-531.

-

- 23. K.W. Tie, J.H. Sim, J.Y. Tey, W.H. Yeo, Z.H. Lee, L.Y. Ng, S.T. Bee, T.S. Lee, and L.C. Abdullah, Processes. 13[3] (2025) 667.

-

- 24. L. del-Mazo-Barbara, and M. Ginebra, J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 41[16] (2021) 18-33.

-

- 25. J.H. Choi, K.H. Hwang, U.S. Kim, K.H. Ryu, K.B. Shim, S.M. Kang, and W.S. Cho, J. Ceram. Process. Res. 20[4] (2019) 424-430.

-

- 26. H.K. Nam, T.W. Kang, I.W. Kim, R.Y. Choi, H.W. Kim, and H.J. Park, Food Biosci. 53 (2023) 102772.

-

- 27. P. Diloksumpan, M. de Ruijter, M. Castilho, U. Gbureck, T. Vermonden, P.R. Van Weeren, J. Malda, and R. Levato, Biofabrication. 12[2] (2020) 025014.

-

- 28. S. Ramesh, A. Yaghoubi, K.Y. Sara Lee, K.M. Christopher Chin, J. Purbolaksono, M. Hamdi, and M.A. Hassan, J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 25 (2013) 63-69.

-

- 29. D. Pierantozzi, A. Scalzone, S. Jindal, L. Stīpniece, K. Šalma-Ancāne, K. Dalgarno, P. Gentile, and E. Mancuso, Compos. Sci. Technol. 191 (2020) 108069.

-

- 30. K. Zhu, D. Yang, Z. Yu, Y. Ma, S. Zhang, R. Liu, J. Li, J. Cui, and H. Yuan, Ceram. Int. 46[17] (2020) 27254-27261.

-

- 31. R. Landers, A. Pfister, U. Hübner, H. John, R. Schmelzeisen, and R. Mülhaupt, J. Mater. Sci. 37 (2002) 3107-3116.

-

- 32. A. Wubneh, E.K. Tsekoura, C. Ayranci, and H. Uludağ, Acta Biomater. 80 (2018) 1-30.

-

- 33. Z. Jia, X. Xu, D. Zhu, and Y. Zheng, Prog. Mater. Sci. 134 (2023) 1011072.

-

- 34. L.C. Gerhardt, and A.R. Boccaccini, Materials. 3[7] (2010) 3867-3910.

-

- 35. Q. Liu, T. Li, S.W. Gan, S.Y. Chang, C.C. Yen, and W. Zhai, Addit. Manuf. 61 (2023) 103332.

-

- 36. S.S. Sun, H.L. Ma, C.L. Liu, C.H. Huang, C.K. Cheng, and H.W. Wei, Clin. Biomech. 23[1] (2008) S39-S47.

-

- 37. G. Krishnamurithy, S. Mohan, N.A. Yahya, A. Mansor, M.R. Murali, H.R. Balaji Raghavendran, R. Choudhary, S. Sasikumar, and T. Kamarul, PLoS. One. 14[3] (2019) 0214212.

-

- 38. R. Choudhary, A. Chatterjee, S.K. Venkatraman, S. Koppala, J. Abraham, and S. Swamiappan, Bioact. Mater. 3[3] (2018) 218-224.

-

- 39. H. Zhang, C. Jiao, Z. Liu, Z. He, M. Ge, Z. Tian, C. Wang, Z. Wei, L. Shen, and H. Liang, J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 121 (2021) 104642.

-

- 40. U.K. Roopavath, S. Malferrari, A. Van Haver, F. Verstreken, S.N. Rath, and D.M. Kalaskar, Mater. Des. 162 (2019) 263-270.

-

This Article

This Article

-

2025; 26(6): 1067-1073

Published on Dec 31, 2025

- 10.36410/jcpr.2025.26.6.1067

- Received on Jul 23, 2025

- Revised on Oct 24, 2025

- Accepted on Oct 28, 2025

Services

Services

- Abstract

introduction

method and materials

results and dicussion

conclusion

- Acknowledgements

- References

- Full Text PDF

Shared

Correspondence to

Correspondence to

- Wei Hong Yeo

-

Department of Mechanical and Materials Engineering, Lee Kong Chian Faculty of Engineering and Science, Universiti Tunku Abdul Rahman, 43000 Kajang, Selangor, Malaysia

Tel : +603 9086 0288 - E-mail: yeowh@utar.edu.my

Copyright 2019 International Orgranization for Ceramic Processing. All rights reserved.

Copyright 2019 International Orgranization for Ceramic Processing. All rights reserved.