- Corrosion behavior of MgAl2O4-Mg2TiO4 sagger for calcination of LNCM (LiNi1-x-yCoxMnyO2)-based secondary battery cathode materials

Nayoung Ham and Kangduk Kim*

Department of Advanced Material Engineering, Kyonggi University, Suwon, South Korea

This article is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

In this study, Mg2TiO4 (inverse spinel) was added to the MgAl2O4 (spinel) sagger, used for calcination of LNCM (LiNi1-x-yCoxMnyO2)-based secondary battery cathode materials, to improve the corrosion behavior by the cathode materials. Mg2TiO4 according to the molar ratio of MgO/TiO2 was sintered by the solid phase synthesis method and added to MgAl2O4 sagger. The highest Mg2TiO4 crystal phase fraction (97.25%) was obtained for MgO:TiO2 = 67:33 (molar ratio) at 1350 ℃ for 3 h. The difference in thermal expansion coefficient was similar to that of the conventional MgAl2O4 (1.81 × 10-6/℃). After the corrosion behavior test of MgAl2O4 sagger containing Mg2TiO4 with cathode material precursors (Li2CO3:NCM811 = 1.1:1 (mol%)) at 950 ℃ for 10 h, the microstructure of the cross-section was analyzed by scanning electron microscopy. The sagger containing Mg2TiO4 formed a thin lithium reaction layer compared to the sagger containing only MgAl2O4.

Keywords: MgAl2O4-Mg2TiO4 solid solutions, Spinel, Corrosion, Sagger, Cathode materials.

Lithium-ion batteries with high capacity and energy density are widely used in wireless communications, consumer electronics, and new energy vehicles [1-4]. As the most important component of lithium-ion batteries, cathode materials have attracted increasing attention [5, 6]. Among the cathode materials for conventional lithium-ion batteries, Ni-rich layered lithium transition-metal oxides (LiNi1-x-yCoxMnyO2) have been of particular interest as high-capacity cathode materials in the past decade due to their high energy density (>200 mAhg-1), low toxicity, and low cost [7-9].

Cathode material calcination is a process of sintering cathode materials by placing LNCM precursor in a refractory ceramic (hereinafter referred to as sagger) container and calcination at 800-1100 ℃ for 10-12 h [10]. The raw materials that comprise the sagger are typically a mixture of 3Al2O3·2SiO2 (mullite), 2MgO·2Al2O3·5SiO2 (cordierite), MgO·Al2O3 (spinel), and Al2O3 (corundum) [11, 12]. However, during the calcination of the cathode materials, the relatively light Li+ ions in the cathode materials diffuse into the pores and vacancies of the sagger and react with the SiO2 and Al2O3 comprising the sagger to form lithium compounds, which cause cracks and corrosion due to the difference in thermal expansion coefficient between the sagger and conventional sagger materials [13-16]. The slagging and spalling reduce the life cycle of the sagger and contaminate the product, which seriously affects the production of cathode materials and quality of the product [17, 18]. Therefore, research on development of a sagger with an excellent corrosion resistance during cathode material calcination to increase the life cycle of the sagger is underway [19, 20].

Among the raw materials used in sagger, MgAl2O4 has a cubic crystal structure and excellent chemical, thermal, and mechanical properties such as a high melting point (2135 ℃), good thermal shock stability, low thermal conductivity and dielectric constant, and excellent corrosion resistance due to its stable chemical relationship with alkali minerals and oxides [21-26]. MgAl2O4 with a spinel crystal structure is composed of a face-centered cubic structure of oxygen ions. The unit cell is composed of 32 O2- ions, A2+ ions (A = Mg, Fe, Ca, Zn, etc.) with a 64-site tetrahedral structure, and B3+ (B = Al, Fe, etc.) ions with a 32-site octahedral structure [27-29]. The voids that exist between the lattices of the three-dimensional network exhibit high Li+ ion diffusion rates. Li+ ions have lower diffusion rates in the octahedra than in the tetrahedra [30]. Generally, various additives including ZnO, CeO2, La2O3, Sm2O3, and TiO2 are used to prepare a high-density MgAl2O4. TiO2 is the most effective additive to prepare a high-density MgAl2O4 [31, 32]. In addition, the Mg2TiO4 inverse spinel structure with TiO2 is as the spinel structure of MgAl2O4, which is favorable for lattice substitution [33]. Mg2TiO4 heterogeneous nucleating agent improves the sintering behavior and microstructure of MgAl2O4, showing a decrease in sintering temperature, a decrease in porosity, and an increase in mechanical strength [34]. Mg2TiO4 inverse spinel structure and MgAl2O4 spinel structure face-centered cubic structures with similar tetrahedral and octahedral structures, indicating that the lattice substitution is facilitated during sintering [33, 34].

In this study, Mg2TiO4 with an inverse spinel structure was sintered and mixed with MgAl2O4 with a spinel structure to prepare a sagger for cathode material calcination. The corrosion behavior according to the microstructural and crystalline phase changes of MgAl2O4-Mg2TiO4 sagger under LNCM cathode material calcination were evaluated.

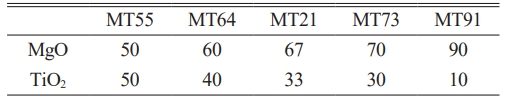

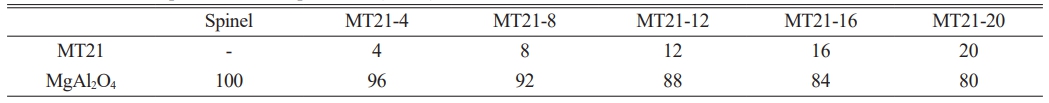

Mg2TiO4 was prepared using MgO (3N, Kojundo Chemicals, Ltd., Japan, Ca. 11) and TiO2 (3N, Kojundo Chemicals, Ltd., Japan, Ca. 1) as starting materials. For mixing and grinding of the raw materials, dry ball milling was performed for 12 h to mix MgO and TiO2 with zirconia balls (diameter = 5, 10 mm) according to the mixing ratio shown in Table 1. The mixed raw materials were molded into round (Φ = 30 mm) specimens using a hydraulic press (3851-0. Carver, USA) at 5 ton/60 s and sintered in a SiC box furnace at 1350 °C for 3 h (temperature increase rate = 5 °C/min). To grind and mix the sintered Mg2TiO4 and MgAl2O4 (Mirae Ceratec, Korea), dry ball milling was performed according to the mixing ratio in Table 2. The mixed raw materials were molded into round (Φ = 30 mm) specimens using a hydraulic press (3851-0. Carver, USA) at 6 ton/60 s, and sagger specimens were prepared by sintering at 1350 °C for 3 h (temperature increase rate = 5 °C/min) in a SiC box furnace.

X-ray diffraction (XRD, SmartLab, Rigaku, Japan) at 4º/min was carried out to analyze the crystalline phase and crystallinity of Mg2TiO4 according to the composition ratio in Table 1. A quantitative analysis of the crystalline phase was performed using the Rietveld method. The thermal expansion coefficient of Mg2TiO4 was measured using a thermomechanical analyzer (TMA 402 F3, Netzsch, Germany) at a temperature increase rate of 10º/min in the range of room temperature (RT)–900 ℃. The changes in crystalline phase and lattice constants of the specimens according to the mixing ratio in Table 2 were observed by an XRD (Empyrean, Malvern Panalytical, UK) analysis at 4º/min and Rietveld method. The composition and valence state of the specimen were observed using X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS, OLS40-SU, Olympus Corporation, Japan). The microstructure of the specimen cross-section surface was observed using the backscattered electron (BSE) mode of scanning electron microscopy (SEM, Nova Nano SEM450, FEI Company, USA).

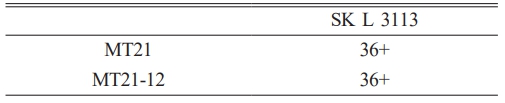

To analyze the corrosion behavior to lithium, LNCM raw materials were prepared by mixing Li2CO3 (4N, Kojundo Chemicals, Ltd., Japan) and N0.8C0.1M0.1(OH)2 (Rov Co. Ltd., Incheon, Korea) powders at 1.1:1 (mol%). The mixed LNCM powders were molded into circular (Φ = 20 mm) specimens using a hydraulic press at 6 ton/20 s, placed on the specimens prepared according to the mixing ratio in Table 2, and subjected to a corrosion test was then performed using an electric furnace at 950 ℃ for 10 h (temperature increase rate = 5 ℃/min). After the corrosion experiment, the microstructure changes and composition of the specimen cross-section surface were observed by SEM (Nova Nano SEM450, FEI Company, USA) using the BSE mode and energy-dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) (Noran system 7, Thermo scientific, USA) analysis. Depth profile was analyzed in 100-μm increments by XRD (PANalytical, AERIS, UK) at 4º/min to observe the crystalline phase changes. For the corrosion depth analysis, three specimens were prepared for each composition and measured repeatedly. The thermal expansion coefficient of spinel, MT21-12, and γ-LiAlO2 (Li2CO3-4N, Kojundo Chemicals, Ltd, Japan, Al2O3-Kojundo chemicals, Ltd., Japan, 4N) was measured using a thermomechanical analyzer (TMA 402 F3, Netzsch, Germany) at a temperature increase rate of 10º/min in the range of room temperature (RT)–900 ℃. The refractory properties (KS L 3113) of MT21 and MT21-12 was analyzed to confirm their stability in high temperature processes.

Synthesis of Mg2TiO4

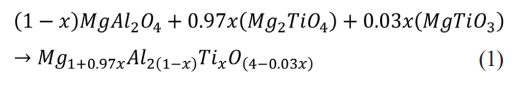

Fig. 1 shows the XRD analysis of specimens sintered at 1350 °C for 3 h using the composition ratio in Table 1. For the MT55 specimen, a single crystalline phase of geikielite (MgTiO3, ICSD Ref. codes: 98-006-5794) was observed. As the content of MgO increased, the geikielite crystalline phase content decreased and qandilite (Mg2TiO4, ICSD Ref. codes: 98-009-6853) crystalline phase was observed. The qandilite crystal phase has an inverse spinel structure, where half of the Mg2+ ions are in a tetrahedral structure, while the remaining Mg2+ and Ti4+ ions are in an octahedral structure. The Mg2TiO4 inverse spinel structure and MgAl2O4 spinel structure are face-centered cubic with tetrahedral and octahedral structures. They are similar in terms of crystal structure, which indicates that the lattice substitution is facilitated during sintering [33, 34].

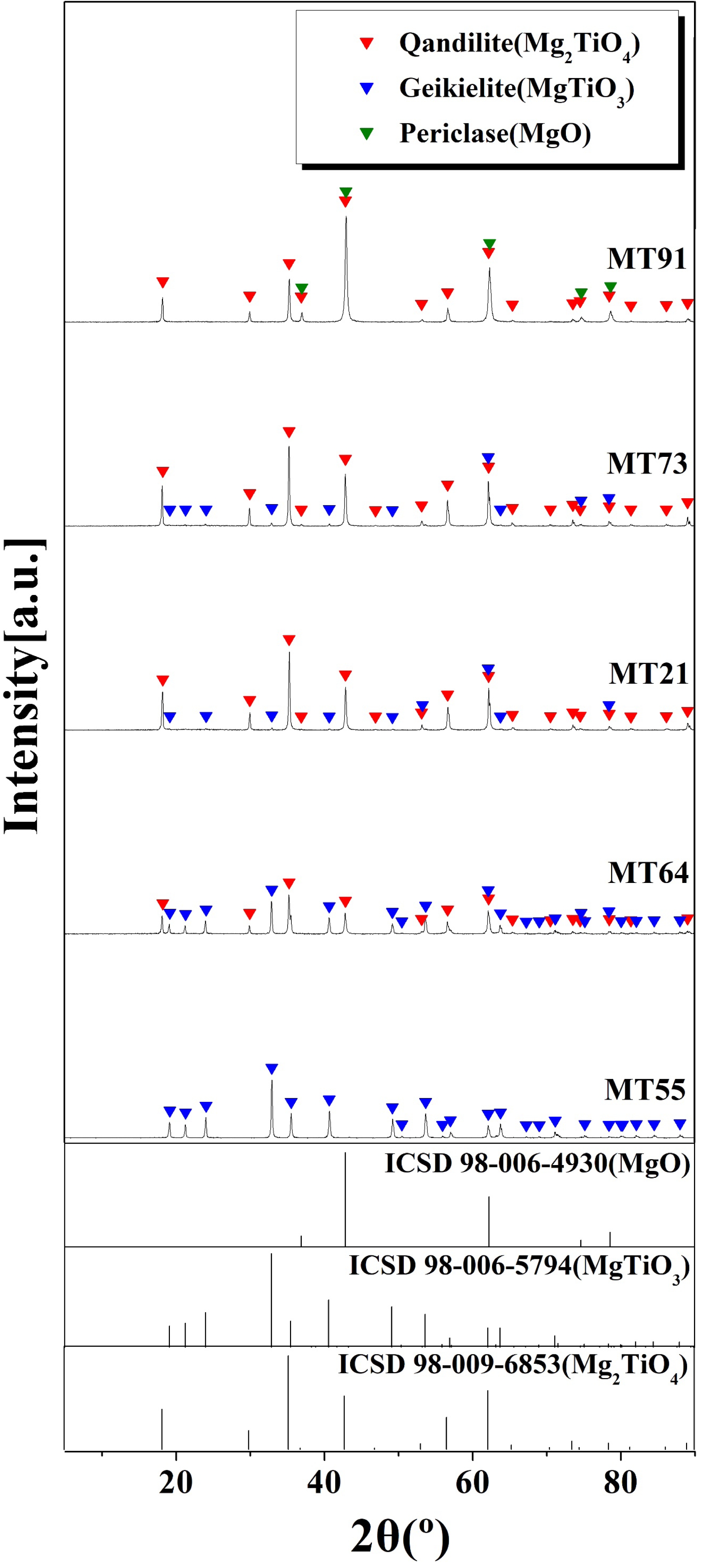

Fig. 2 shows the crystalline phase fractions of specimens sintered at 1350 °C for 3 h using the Rietveld method for the composition ratio in Table 1. In general, Rwp of 10% or lower indicate a high similarity between the calculated and observed diffraction patterns. All specimens exhibited Rwp of 10% or lower [35]. The Mg2TiO4 crystalline phase was present in all specimens except MT55. The content of the target crystalline phase, Mg2TiO4, was highest, 97.25%, in MT21. Mg2TiO4 exhibits a crystal structure of inverse spinel with a cubic symmetry with lattice parameters of a = b = c = 8.4415 Å. MT21 with a lattice parameter of a = b = c = 8.44169(4) Å formed an inverse spinel structure with Rwp of 6.74, S of 2.5892, Rp of 4.66, and χ2 of 6.7039 [36].

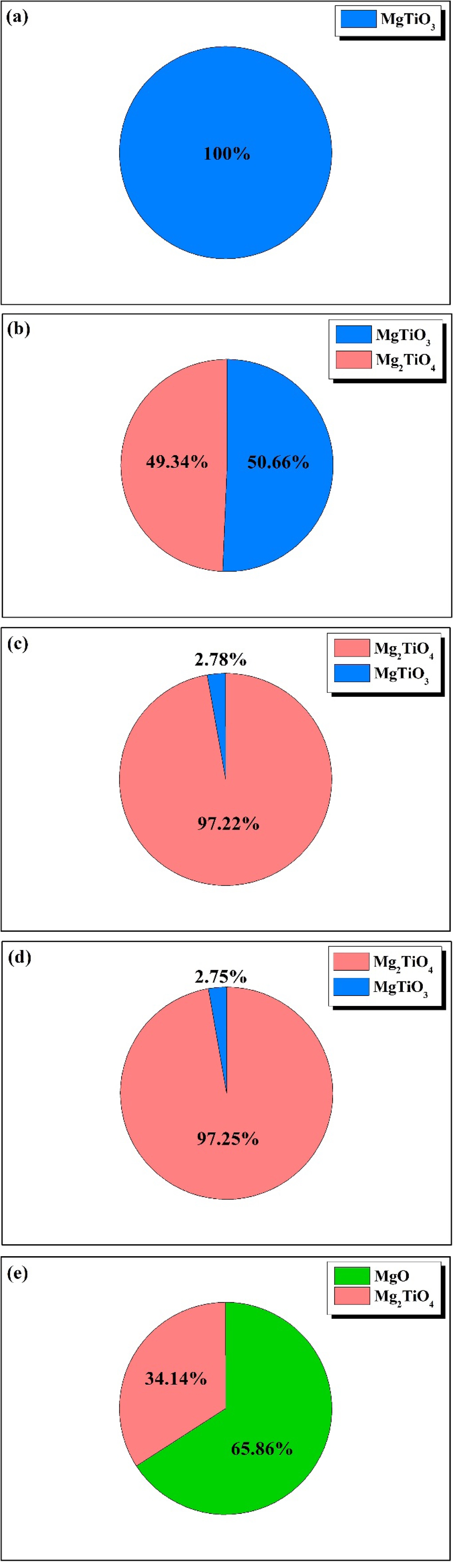

Fig. 3 shows the crystallinity of the specimens sintered at 1350 °C for 3 h using the composition ratio in Table 1. High crystallinities of approximately 99% were observed for all specimens regardless of the composition ratio. MT21 had the highest crystallinity of 99.97%.

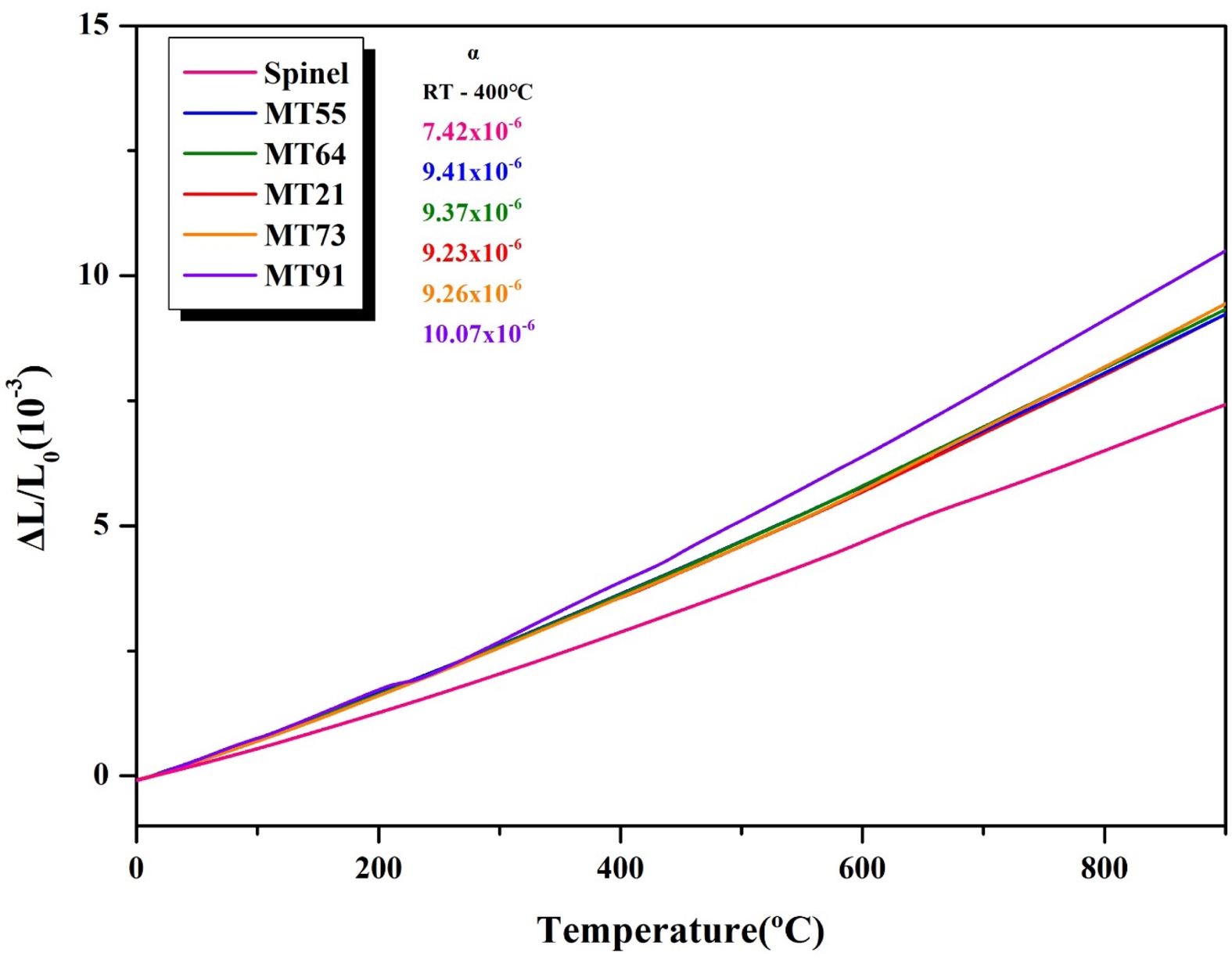

Fig. 4 shows the thermal expansion coefficient of MgAl2O4, and those of specimens sintered at 1350 ℃ for 3 h with the composition ratio in Table 1. MgAl2O4 exhibited the lowest thermal expansion coefficient (7.42 × 10-6/℃, RT–400 ℃), while MT91 exhibited the highest

thermal expansion coefficient (10.07 × 10-6/℃). MT55, MT64, MT21, and MT73 exhibited thermal expansion coefficients ranging from 9.23 to 9.41 × 10-6/℃. The difference in thermal expansion coefficient between MgAl2O4 and MT21 (9.23 × 10-6/℃) was 1.81 × 10-6/℃, which is smaller than those of other sagger materials (mullite: 5.5 × 10-6/℃, cordierite: 1–2 × 10-6/℃) [37]. In this study, MT21 specimens with higher crystal phase fractions and crystallinities of Mg2TiO4 and smaller differences in thermal expansion coefficient from the conventional MgAl2O4 were added to MgAl2O4.

Synthesis of MgAl2O4-Mg2TiO4 solid solutions

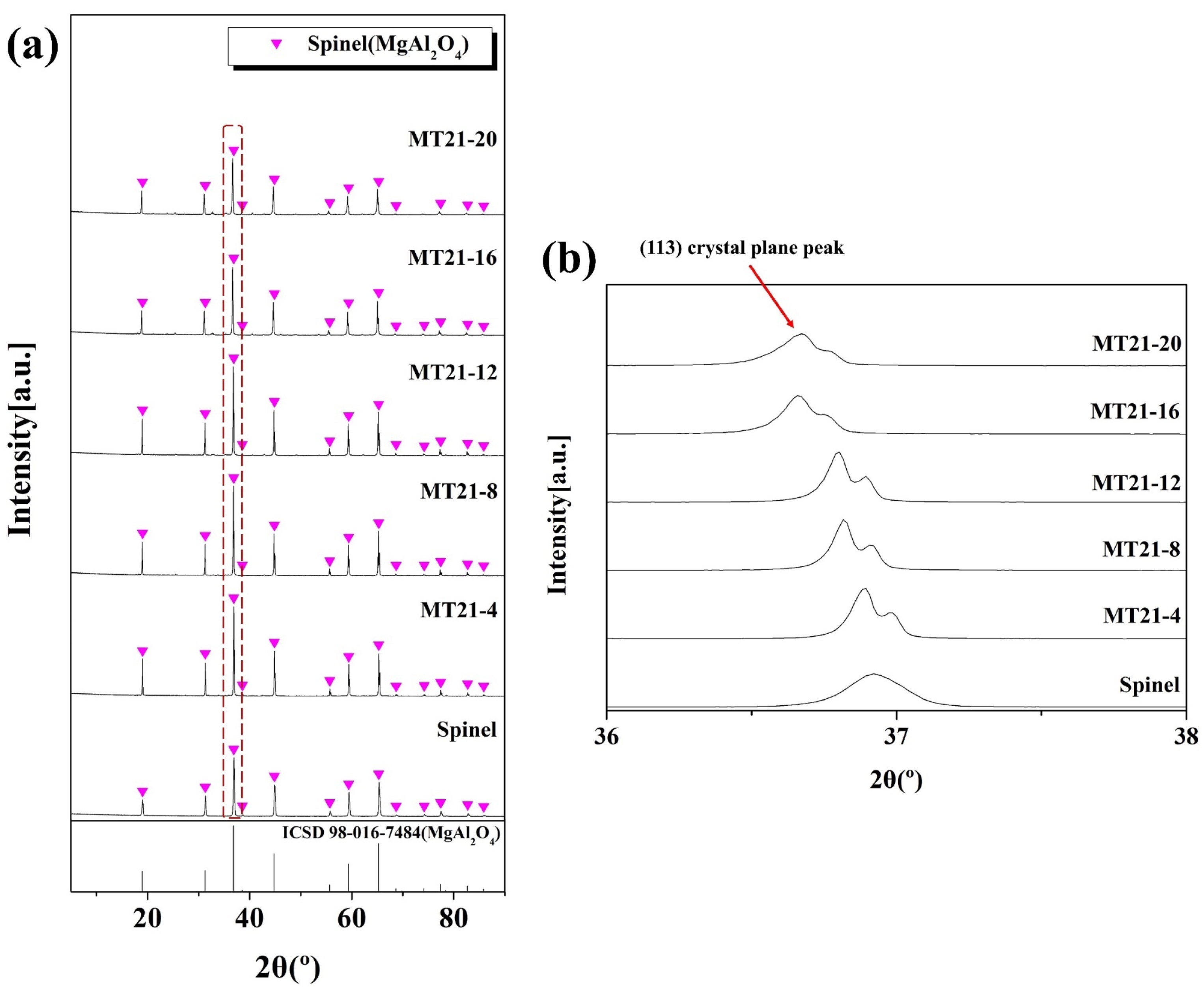

Fig. 5 shows the XRD analysis results of specimens sintered at 1350 °C for 3 h with MT21 added to MgAl2O4 according to the mixing ratio in Table 2. The spinel (MgAl2O4, ICSD Ref. codes: 98-016-7484) crystalline phase was observed in all specimens in Fig. 5(a). The crystalline phase peak of spinel increased as the amount of added MT21 increased. The spinel peak gradually decreased starting from the specimen with MT21-12. Fig. 5(b) shows an enlarged view of the 36–38° range of the XRD peak in Fig. 5(a). As the substitution amount of MT21 increases, the (113) crystal plane peak clearly shifts to smaller angles, which is likely due to the expansion of the cell volume as Mg2TiO4 diffuses into MgAl2O4 to form a solid solution [34].

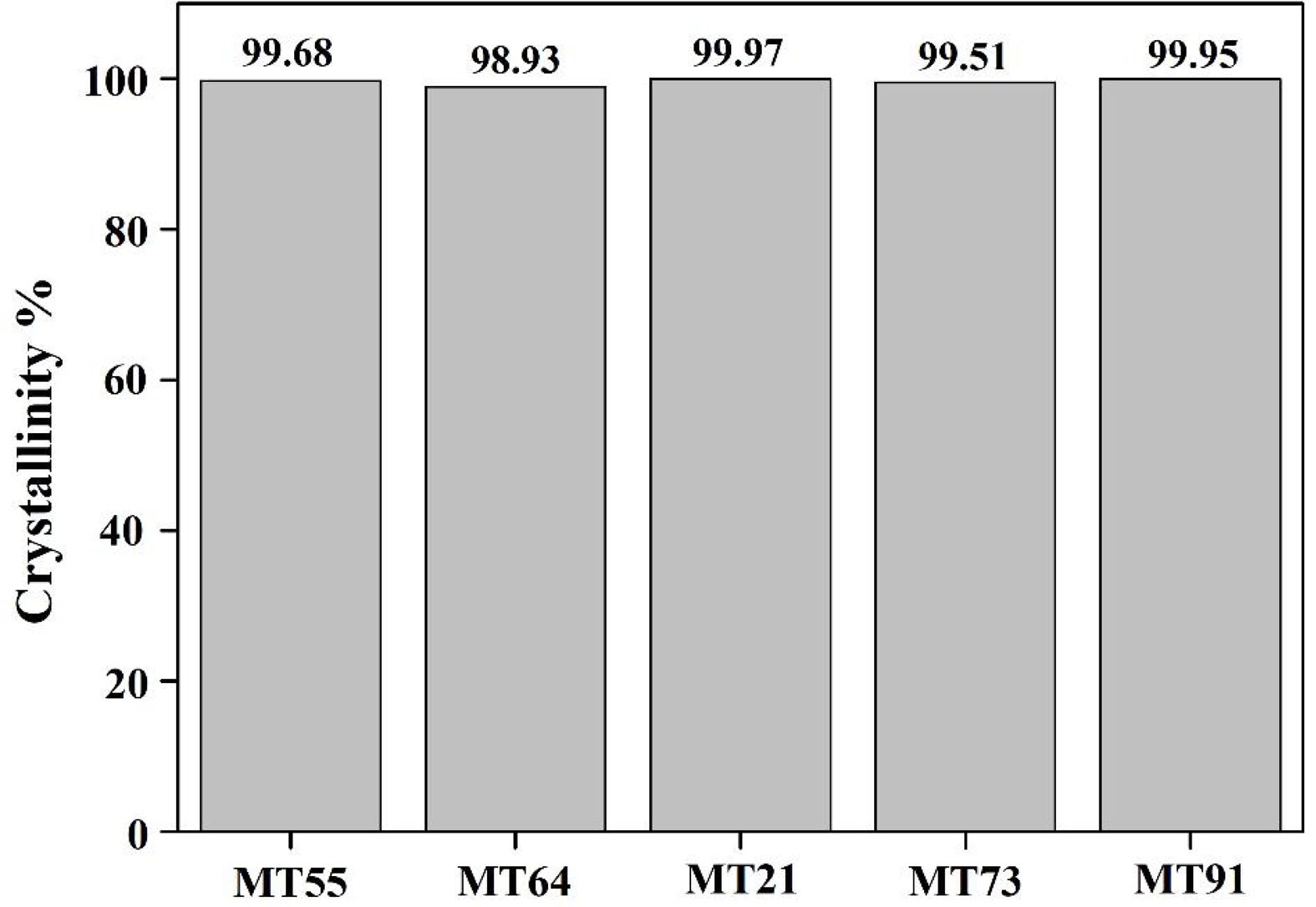

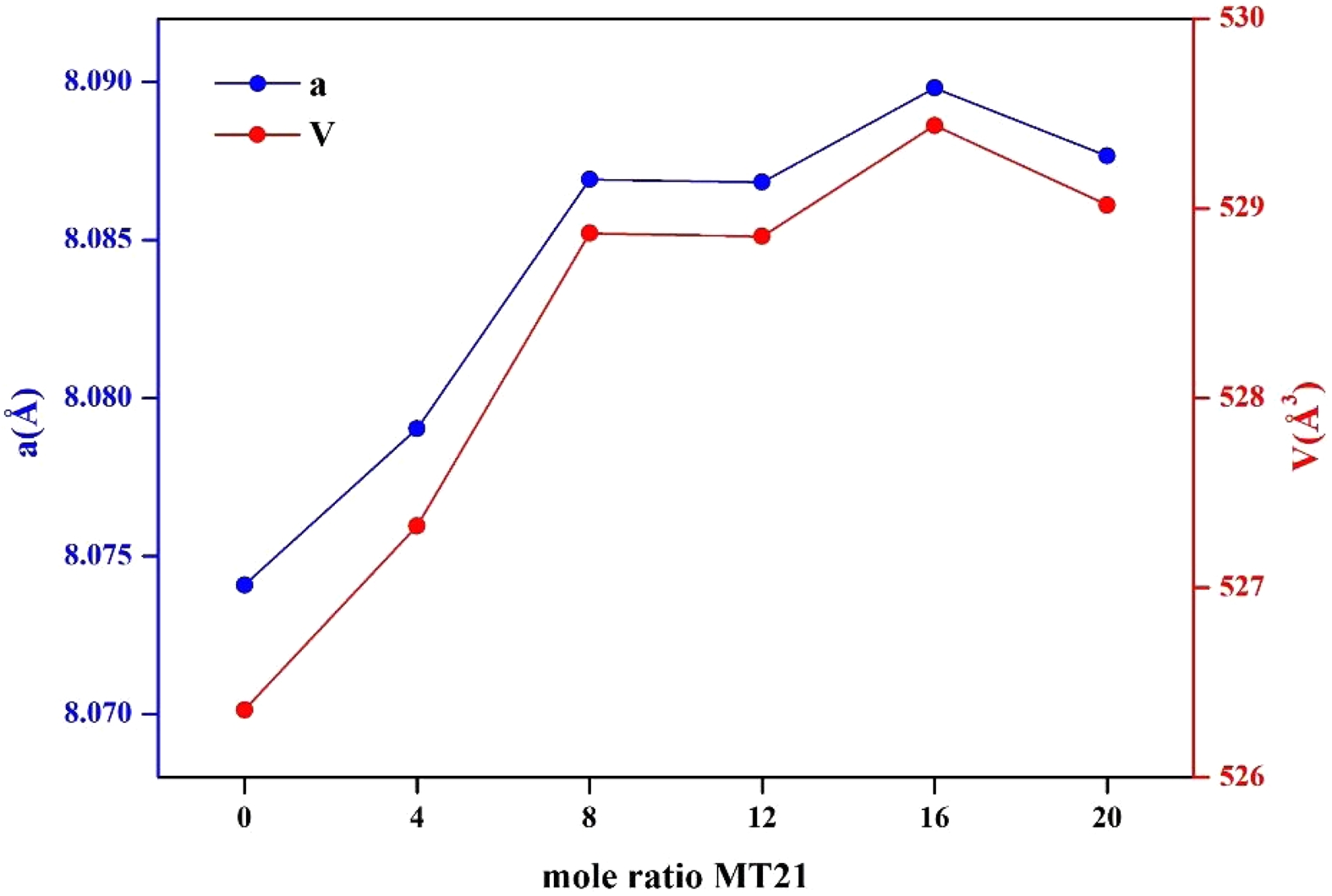

Fig. 6 shows the variations in lattice parameters (a) and lattice volumes (V) of the specimens with the change in MT21 substitution amount, obtained using the Rietveld method. The lattice parameters and lattice volumes of the specimens with added MT21 are increased compared to those without added MT21, because the expansion of lattice volume occurs due to the substitution of larger Mg2+ (0.72 Å) and Ti4+ (0.61 Å) ions compared to Al3+ (0.53 Å) ions in MgAl2O4. This yields a MgAl2O4–Mg2TiO4 spinel solid solutions, which is consistent with the peak results of the (113) crystal plane in Fig. 5 [34, 38]. The MgAl2O4–Mg2TiO4 solid solutions upon substitution of MT21 is formed through the following reaction [39]:

An increase in lattice expansion was observed in MT21-16 and MT21-20 compared to MT21-8. However, the lattice expansion was smaller starting from MT21-12, which could be attributed to the lack of sufficient thermal energy for the larger Mg2+ (0.72 Å) and Ti4+ (0.61 Å) ions to overcome the lattice mismatch and be substituted compared to the Al3+ (0.53 Å) ions [40, 41].

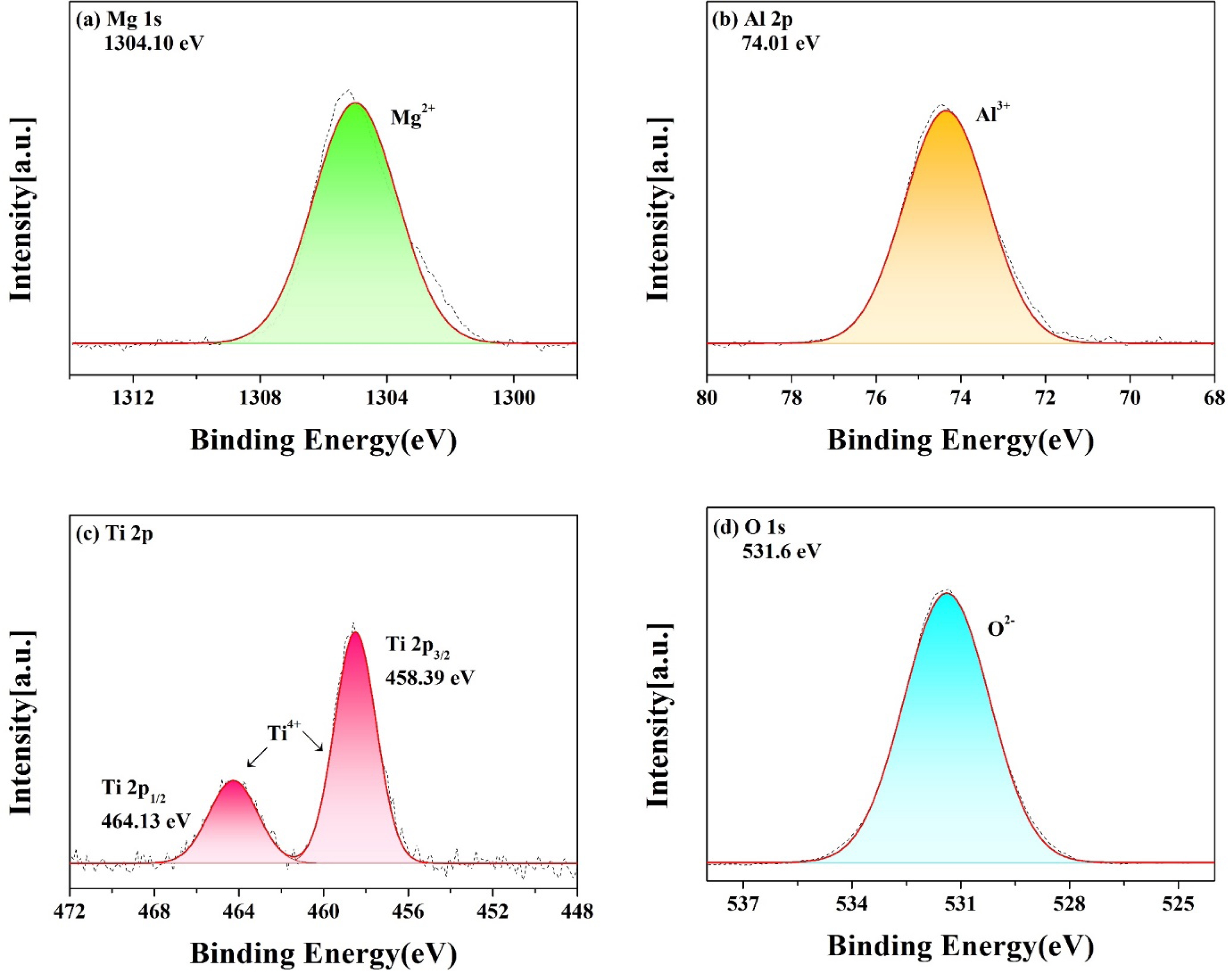

Fig. 7 shows the XPS results for the binding energy of the specimen with MT21 added at 12 mol% and sintered at 1350 °C for 3 h. The binding energies of Mg2+, Al3+, and O2- were 1304.10 eV, 74.01 eV, and 531.6 eV, respectively, and only Mg, Al, Ti, and O were detected in the specimen with MT21 added at 12 mol%. Ti4+ is unstable at high temperatures and converts to Ti3+, as shown in Fig. 7(c), and the binding energies of Ti 2p3/2 and Ti 2p1/2 of Ti4+ are 458.39 eV and 464.13 eV, respectively, which are consistent with the binding energy values of Ti4+ reported by Lai et al. [42]. This indicates that Mg2TiO4 diffuses into MgAl2O4 to form a MgAl2O4-Mg2TiO4 solid solution as shown in the XRD analysis in Fig. 5. The high charge of Ti4+ more strongly attracts the oxygen ions around the octahedron, and since Ti4+ has a higher charge state than Al3+, the energy barrier increases when lithium ions pass through the octahedral site [43, 44]. In general, lithium ions move in the path of tetrahedron (8a) → octahedron (16c) → tetrahedron (8a) in the spinel structure, and as Ti4+ is substituted for the Al3+ site, the size of the vacancy around the octahedron decreases, which reduces the diffusion path of lithium ions [43-46].

Corrosion behavior of MgAl2O4-Mg2TiO4 solid solutions

Fig. 8(a) shows images of the specimens before and after the LNCM cathode material corrosion reaction. Especially, no surface spalling was observed regardless of the MT21 substitution amount, and yellowing due to the lithium corrosion reaction was observed on the of all specimens. The yellowing is due to the diffusion of Li+ ions through hopping into the pores and vacancies of the sagger during the cathode material corrosion reaction. The diffusion of Li+ ions cause a difference in the thermal expansion coefficient of the newly formed phase and existing phase, resulting in cracking [17, 30]. To examine the crack formation and delamination induced by thermal shock, the LNCM reaction test was performed ten times, and the resulting microstructures are shown in Fig. 8(b). No severe cracking or delamination was observed in any of the specimens.

Fig. 9 and Fig. 10 show the results of the analysis of the cross-section surfaces of the specimens before the corrosion reaction by the BSE mode of SEM and EDS. Microscopic pores were observed in all specimens. Mg (dark gray) and Al (gray) elements were identified in the specimens with MgAl2O4 and MT21 added at 4 mol%. Ti (light gray) elements were observed starting from the specimen with 8 mol% substitution of MT21. The distribution of Ti elements increased with the MT21 substitution.

Fig. 11 shows Depth profile analyzed by XRD while grinding the specimen in the depth direction after the LNCM cathode material corrosion reaction. The reaction with the LNCM during the corrosion reaction resulted in various products. LiAlO2, Ni6.8Mn0.6O8, Li5AlO4, Li0.14Co0.86O, and LiMn2O4 crystalline phases were observed on the surface of MgAl2O4 sagger. However, the LiAlO2 crystalline phase disappeared as the corrosion depth increased, and Li0.59Ni1.01O2 crystalline phase existed from a depth of 400 µm. In the specimen polished to a depth of 800 µm, Li0.59Ni1.01O2 crystalline phase existed, but the second highest peak disappeared. In the case of MT21-12, LiAlO2, Li0.61CoO2, and Ni6.4Mn0.8O8 crystal phases were observed on the surface, and as the corrosion depth increased, the LiAlO2 crystal phase disappeared, and the Li0.59Ni1.01O2 crystal phase existed from 300 µm depth. In the specimen polished to a depth of 700 µm, the Li0.59Ni1.01O2 crystal phase existed, but the second highest peak disappeared. The smaller corrosion depth of MT21-12 compared to MgAl2O4 is due to the lattice expansion of MgAl2O4, which has a spinel crystal structure due to the substitution of Mg2TiO4. The lattice expansion of MgAl2O4 is thought to reduce the vacancy of MgAl2O4 and reduce the corrosion caused by the diffusion of Li+ ions [47, 48].

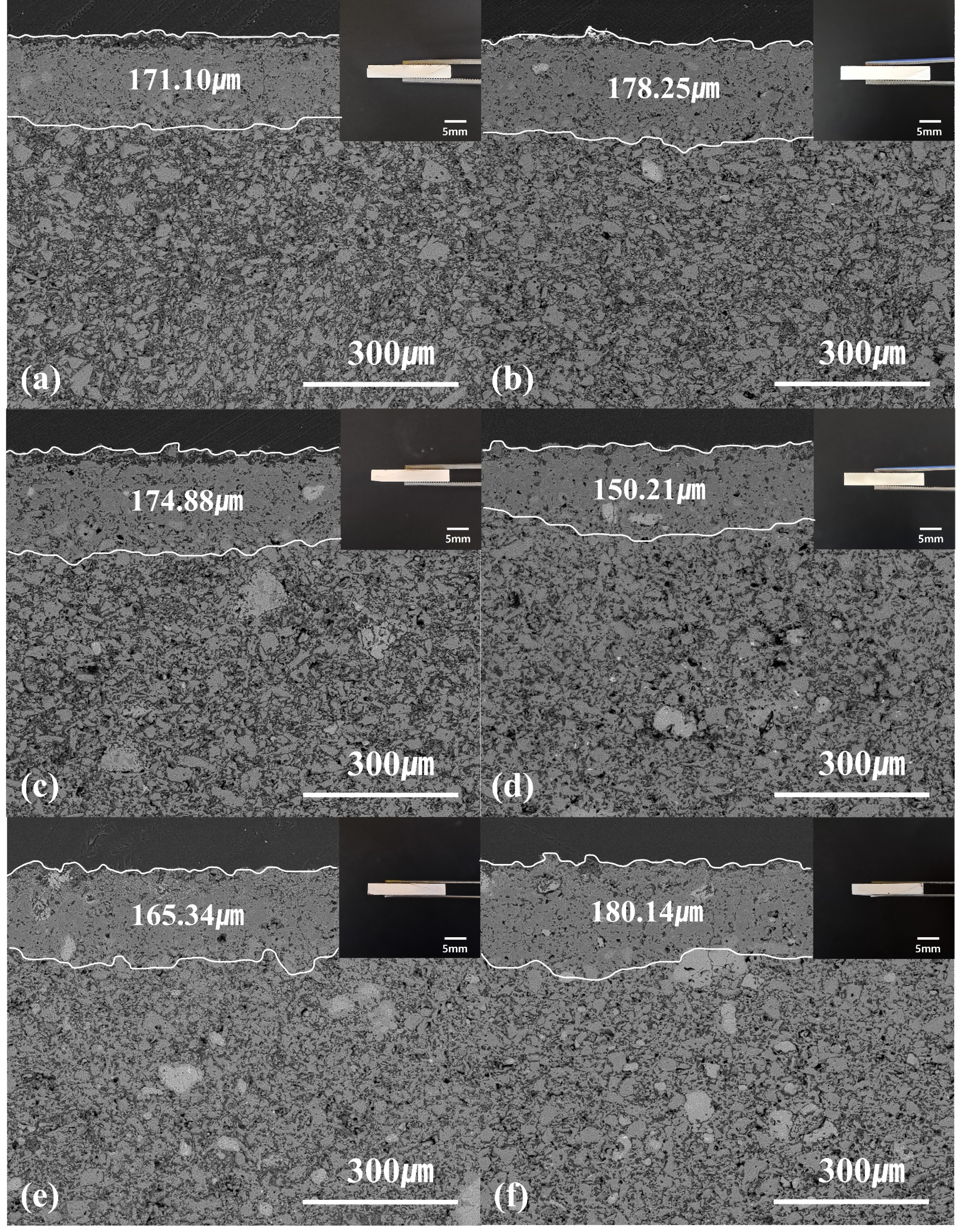

Fig. 12 shows the microstructure of the cross-section surface of the specimen after the LNCM cathode material corrosion reaction analyzed by the BSE mode of SEM. A surface layer with a relatively denser structure than the inside of the specimen was formed after the corrosion reaction. The thickness of the surface layer was measured 10 times and the average value was 150–180 µm. The crystal phase formed in the surface layer is observed as a LiAlO2 crystal phase, as shown in the depth profile result in Fig. 11, and spalling occurs mainly due to the formed layer of LiAlO2 [49, 50]. It is judged that MT21-12 can suppress the diffusion of Li+ ions because the thickness of LiAlO2 is reduced compared to spinel.

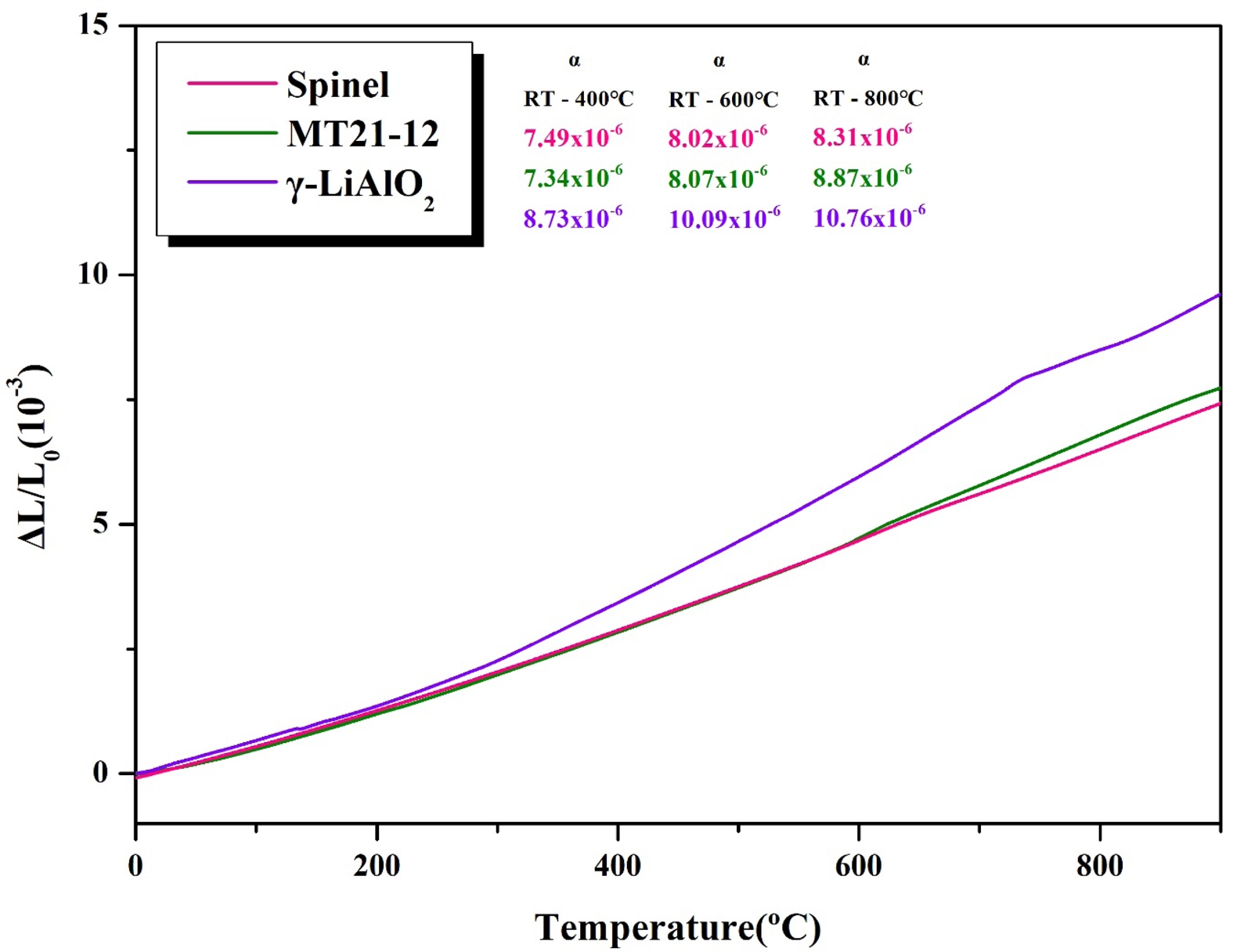

Fig. 13 shows the thermal expansion coefficient of the specimens sintered at 900 °C for 3 h and sintered at 1350 °C for 3 h with 12 mol% addition of spinel and MT21. As shown in Fig. 11 and 12, when the cathode material is generally calcined, the refractory and the cathode material react to mainly generate γ-LiAlO2 [49, 50]. The product expands in volume due to the difference in thermal expansion coefficient from the existing refractory material, resulting in a spalling [17, 49, 50]. The thermal expansion coefficient of MT21-12 (8.87 × 10-6/℃) with 12 mol% Mg2TiO4 added is higher than that of the existing raw material, spinel (8.31 × 10-6/℃, RT–800 ℃). It is judged that this is because MT21-12 has a smaller difference in thermal expansion coefficient with γ-LiAlO2 than spinel, and thus the spalling caused by the difference in thermal expansion coefficient can be suppressed.

Table 3 shows the results of the refractory analysis of the raw materials MT21 with the highest crystal phase fraction of Mg2TiO4 and MT21-12 with the lowest corrosion depth to confirm the structural stability and deformation resistance of the refractory. In general, refractories have a refractory value of SK26 (1580 ℃) or higher, and MT21 and MT21-12 have values of SK36+ (1790 ℃), indicating that they are excellent in corrosion [51].

|

Fig. 1 XRD patterns of the specimens with different MgO/ TiO2 ratio. |

|

Fig. 2 Crystalline phases of the specimens with different MgO/ TiO2 ratio; (a) MT55, (b) MT64, (c) MT73, (d) MT21, (e) MT91. |

|

Fig. 3 Crystallinity of the specimens with different MgO/TiO2 ratio. |

|

Fig. 4 Thermal expansion coefficient of the specimens with different MgO/TiO2 ratio. |

|

Fig. 5 XRD patterns of the specimens with different Mg2TiO4 contents. |

|

Fig. 6 Lattice parameters (a) and cell volume (V) of the specimens with different Mg2TiO4 contents. |

|

Fig. 7 XPS spectra of MT21-12; (a) Mg 1s, (b) Al 2p, (c) Ti 2p, (d) O 1s. |

|

Fig. 8 Surface image of the specimens with different Mg2TiO4 contents after LNCM corrosion; (a) before and after 1st LNCM corrosion reaction, (b) 10th LNCM corrosion reaction. |

|

Fig. 9 BSE image of cross-section of the specimens with different Mg2TiO4 contents; (a) spinel, (b) MT21-4, (c) MT21-8, (d) MT21-12, (e) MT21-16, (f) MT21-20. |

|

Fig. 10 EDS mapping images of cross-section of MT21-12. |

|

Fig. 11 XRD depth profiles of the specimens with different Mg2TiO4 contents after LNCM corrosion; (a) spinel, (b) MT21-12. |

|

Fig. 12 BSE image of cross-sections of the specimens with different Mg2TiO4 contents after LNCM corrosion; (a) spinel, (b) MT21- 4, (c) MT21-8, (d) MT21-12, (e) MT21-16, and (f) MT21-20. |

|

Fig. 13 Thermal expansion coefficient of the spinel, MT21-12, and γ-LiAlO2. |

In this study, Mg2TiO4 with an inverse spinel structure was sintered, and the Li(Ni0.8Co0.1Mn0.1)O2 secondary battery cathode material corrosion behavior of MgAl2O4 with a spinel structure sintered with substitution of Mg2TiO4 was evaluated. In the Rietveld analysis, the highest Mg2TiO4 crystalline phase fraction (97.25%) was obtained for the MgO:TiO2 = 67:33 (molar ratio) composition. The thermal expansion coefficient (1.81 × 10-6/℃) was similar to that of the conventional MgAl2O4. MgAl2O4-Mg2TiO4 sintered with 4, 8, 12, 16, and 20 mol% substitutions of Mg2TiO4 exhibited increases in lattice constant (a) and lattice volume (V) as the amount of Mg2TiO4 substitution increased. XPS of the sample with 12 mol% of Mg2TiO4 added confirmed the formation of a MgAl2O4-Mg2TiO4 spinel solid solution, as Ti4+ existed. Depth profile analysis of the corrosion response of the LNCM cathode materials by XRD showed that the MgAl2O4-Mg2TiO4 sintered material exhibited a corrosion depth of 150.21 µm, smaller than that of the MgAl2O4 sintered material. It was confirmed that spalling was suppressed because the difference in thermal expansion coefficient between MT21-12 and γ-LiAlO2 was smaller than that of spinel. The MgAl2O4-Mg2TiO4 substitution, along with the lattice expansion and Ti4+, provided a superior LNCM corrosion behavior compared to the conventional MgAl2O4 and is expected to be applicable to the sagger for calcination of secondary battery cathode materials in the future.

This work was supported by the Technology Innovation Program (20025022, Key technologies of superior Li-corrosion resistance refractories for manufacturing High-Ni based cathode materials of Li-ion battery) funded By the Ministry of Trade, Industry & Energy (MOTIE, Korea).

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

- 1. X. Duan, H. Zheng, Y. Chen, F. Qian, G. Liu, X. Wang, and Y. Si, Ceram. Int. 46[3] (2020) 2829-2835.

-

- 2. Z. Sun, J. Yu, H. Zhao, S. Sang, H. Zhang, Y. Zhang, and H. He, J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 42[13] (2022) 6255-6263.

-

- 3. Y.W. Yoo, and S.H. Lee, J. Ceram. Process. Res. 23 (2022) 566-569.

-

- 4. S. Imashuku, J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 44[14] (2024) 116661.

-

- 5. E. Kallitsis, A. Korre, G. Kelsall, M. Kupfersberger, and Z. Nie, J. Clean. Prod. 254 (2020) 120067.

-

- 6. J. Jyoti, B.P. Singh, and S. Tripathi, J. Energy. Storage. 43 (2021) 103112.

-

- 7. J.K. Lee, K.M. Choi, W.S. Lee, and J.R. Yoon, J. Ceram. Process. Res. 25[4] (2024) 613-616.

-

- 8. J.M. Lim, T. Hwang, D. Kim, M.S. Park, K. Cho, and M. Cho, Sci. Rep. 7[1] (2017) 39669.

-

- 9. D. Cao, S. Li, Y. Li, J. Tan, and C. Wei, Int. J. Appl. Ceram. Technol. 22[2] (2024) e14944.

-

- 10. D. Ding, G. Ye, and L. Chen, Corros. Sci. 157 (2018) 324-330.

-

- 11. S.M. Logvinkov, G.D. Semchenko, and D.A. Kobyzeva, Refrac. Ind. Ceram. 38[9] (1997) 383-387.

-

- 12. A.L. Schäfer, and V. Schönhof, cfi/Ber. DKG. 100[3] (2023) E39-E42.

- 13. K. Xiang, S. Li, Y. Li, H. Wang, and R. Xiang, Ceram. Int. 48[16] (2022) 23341-23347.

-

- 14. H. Wang, Y. Li, S. Li, B. Yin, X. He, Z. Qiao, and K. Xiang, J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 43[12] (2023) 5390-5397.

-

- 15. B. Yang, B. Yin, H. Chen, and Y. Zheng, Int. J. Appl. Ceram. Technol. 22[2] (2024) e14948.

-

- 16. K. Xiang, S. Li, Y. Li, H. Wang, R. Xiang, and X. He, Int. J. Appl. Ceram. Technol. 20[3] (2023) 1928-1938.

-

- 17. C. Gan, H. Zhang, H. Zhao, Y. Zhang, and H. Liu, Ceram. Int. 49[1] (2023) 907-917.

-

- 18. G. Qu, J. Yang, Y. Wei, S. Zhou, B. Li, and H. Wang, Environ. Manag. 349 (2024) 119438.

-

- 19. C. Gan, H. Zhang, H. Zhao, Y. Zhang, and H. He, Ceram. Int. 48[20] (2022) 30589-3059.

-

- 20. C. Zheng, H. Zhang, H. Zhao, J. Yu, Y. Zhang, and H. Liu, Int. J. Appl. Ceram. Technol. 21[3] (2024) 2342-2356.

-

- 21. Z. Chen, H. Chen, H. Yang, and J. Wang, Ceram. Int. 47[5] (2021) 6513-6520.

-

- 22. I. Ganesh, Int. Mater. Rev. 58[2] (2013) 63-112.

-

- 23. J.G. Li, T. Ikegami, and J.H. Lee, Ceram. Int. 27[4] (2001) 481-489.

-

- 24. G.T.K. Fey, Z.F. Wang, C.Z. Lu, and T.P. Kumar, J. Power. Sour. 146[1-2] (2005) 245-249.

-

- 25. E.K. Omid, R. Naghizadeh, and H.R. Rezaie, J. Ceram. Process. Res. 14[4] (2013) 445-447.

-

- 26. J.F. Al-Sharab, F. Cosandey, A. Singhal, G. Skandan, and J. Bentley, J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 89[7] (2006) 2279-2285.

-

- 27. M.F. Zawrah, H. Hamaad, and S. Meky, Ceram. Int. 33[6] (2007) 969-978.

-

- 28. F. Nestola, T. Boffa Ballaran, T. Balic-Zunic, F. Princivalle, L. Secco, and A. Dal Negro, Am. Mineral. 98[11-12] (2007) 1838-1843.

-

- 29. D. Dwibedi, M. Avdeev, and P. Barpanda, J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 98[9] (2015) 2908-2913

-

- 30. J. Bhattacharya, and C. Wolverton, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 15[17] (2013) 6486-6498.

-

- 31. R. Naghizadeh, H.R. Rezaie, and F. Golestani-Fard, Ceram. Int. 37[1] (2011) 349-354.

-

- 32. J. Zhao, Q. Hou, B. Fan, L. Zhang, F. Zhao, X. Luo, D. Qi, and Z. Xie, Ceram. Int. 49[22] (2023) 34490-34499.

-

- 33. T. Wang, L.Q. Chen, and Z.K. Liu, Metall. Mater. Trans. A. 38[3] (2007) 562-569.

-

- 34. J. Zhao, B. Fan, F. Zhao, C. Jiang, J. Li, L. Zhang, and Z. Xie, Ceram. Int. 49[8] (2023) 12551-12562.

-

- 35. M. Verezhak, “Multiscale characterization of bone mineral: new perspectives in structural imaging using X-ray and electron diffraction contrast”(Communauté Universite Grenoble Alpes, 2016). p. 55.

- 36. H. Li, R. Xiang, X. Chen, H. Hua, S. Yu, B. Tang, and S. Zhang, Ceram. Int. 46[4] (2020) 4235-4239.

-

- 37. M.A. Subramanian, D.R. Corbin, and U. Chowdhry, Bull. Mater. Sci. 16[6] (1993) 665-678.

-

- 38. R. Lodha, G. Oprea, and T. Troczynski, Ceram. Int. 37[2] (2011) 465-470.

-

- 39. X. Yang, Y. Lai, Y. Zeng, F. Yang, F. Huang, B. Li, and H. Su, J. Alloy. Compd. 898 (2022) 162905.

-

- 40. M.A. Petrova, G.A. Mikirticheva, A.S. Novikova, and V.F. Popova, J. Mater. Res. 12[10] (1997) 2584-2588.

-

- 41. X. Li, and R. Yang, Phys. Rev. B. 86[5] (2012) 054305.

-

- 42. Y. Lai, C. Hong, L. Jin, X. Tang, H. Zhang, X. Huang, J. Li, and H. Su, Ceram. Int. 43[18] (2017) 16167-16173.

-

- 43. S. Choi, C. Kang, J. Choi, H. Ko, and J. Lee, Korean Intellectual Property Office. (2016).

- 44. K. Jun, Y. Chen, G. Wei, X. Yang, and G. Ceder, Nat. Rev. Mater. 9[12] (2024) 887-905.

-

- 45. K. Tateishi, D. du Boulay, and N. Ishizawa, Appl. Phys. Lett. 84[4] (2004) 529-531.

-

- 46. H.J. Jeong, and S.W. Lee, “Theoretical insight of fast Li diffusion at Li-excess spinel lithium manganese oxide” (Hanyang University, 2021) p.5.

- 47. P. Zhai, L. Chen, S. Hu, X. Zhang, D. Ding, H. Li, and G. Ye, Int. J. Appl. Ceram. Technol. 16[1] (2019) 287-293.

-

- 48. A. Valenzuela-Gutierrez, and J. Lopez-Cuevas, SN. Appl. Sci. 1[7] (2019) 784.

-

- 49. M. Ju, Y. Liang, S. Li, M. Cai, J. Nie, and Z. Shan, J. Ceram. Soc. Japan. 128[7] (2020) 368-374.

-

- 50. P. Zhai, L. Chen, Y. Yin, S. Li, D. Ding, and G. Ye, J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 38[4] (2018) 2145-2151.

-

- 51. Y.P. Moon, and J.Y. Choi, J. Nucl. Fuel Cycle Waste Technol. 14[2] (2016) 169-178.

-

This Article

This Article

-

2025; 26(6): 1055-1066

Published on Dec 31, 2025

- 10.36410/jcpr.2025.26.6.1055

- Received on Aug 22, 2025

- Revised on Oct 29, 2025

- Accepted on Oct 31, 2025

Services

Services

- Abstract

introduction

experiment procedure

results and discussion

conclusion

- Acknowledgements

- Conflict of Interest

- References

- Full Text PDF

Shared

Correspondence to

Correspondence to

- Kangduk Kim

-

Department of Advanced Material Engineering, Kyonggi University, Suwon, South Korea

Tel : +82-10-6206-6290 - E-mail: solidwaste@kyonggi.ac.kr

Copyright 2019 International Orgranization for Ceramic Processing. All rights reserved.

Copyright 2019 International Orgranization for Ceramic Processing. All rights reserved.