- Effects of additives and granule powder on liquid phase sintering behavior and properties of black alumina

Byung-Kon Leea, Min-Kwon Parkb, Sin-Il Goc and Sang-Jin Leeb,d,*

aJeonnam Technopark, Suncheon 58034, Republic of Korea

bDepartment of Advanced Materials Science and Engineering, Mokpo National University, Muan 58554, Republic of Korea

cResearch Institute of Ceramic Processing, HK Tech Ltd. Co., Mokpo 68618, Republic of Korea

dResearch Institute of Ceramic Industry and Technology, Mokpo National University, Muan 58554, Republic of KoreaThis article is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Electrostatic charge control and reflectance reduction are essential in semiconductor and display lithography processes. White alumina, an electrical insulator, often causes charge accumulation and light scattering, which can destabilize these processes. To overcome these drawbacks, black alumina ceramics with high density and low reflectivity are required. In this study, domestic alumina powder was mixed with additives mainly composed of Co₂O₃ and TiO₂, and the effects of additive content and sintering temperature on densification, hardness, reflectivity, and color were investigated. In particular, the role of spray granulation was examined by comparing compacts prepared with and without granulation, revealing its importance in achieving homogeneous packing and improved sintering behavior. The low melting point of Co₂O₃ facilitated liquid-phase sintering at relatively low temperatures, and nearly full densification was achieved around 1350 °C. Stable black coloration was also obtained over a wide additive range (5-35 wt%). These results demonstrate that black alumina ceramics with controlled optical and mechanical properties can be fabricated at relatively low temperatures through appropriate additive selection and granulation processing.

Keywords: Black alumina, Granule powder, Liquid phase sintering, Sintering density, Hardness, Reflectivity.

Alumina (Al₂O₃) is widely used in semiconductors, electronic components, refractories, abrasives, and catalysts because of its high hardness, wear resistance, thermal stability, corrosion resistance, and excellent electrical insulation [1-5]. In advanced semiconductor manufacturing and display lithography processes, electrostatic charge control and reflectance reduction are required. However, white alumina, as an insulator, can generate static charges and scatter light, both of which adversely affect process stability. Display lithography processes, in particular, where fine patterns are defined through optical exposure, low-reflectivity black alumina is necessary to minimize undesirable reflections from surrounding components [6, 7].

Black alumina is a functional ceramic that combines the mechanical advantage of alumina with low reflectivity and tailored electrostatic characteristics. These features make it suitable for components used in semiconductor and display photolithography processes [8]. Recently, densified black alumina has been utilized as a key component in the deposition and etching equipment for photoprocessing in the manufacturing of sixth-generation high-resolution panels, specifically for controlling light reflection and adjusting resistance. Black alumina is produced by adding small amounts of transition-metal oxides to alumina, resulting in controlled optical and electrical properties. Typical additives include TiO₂, Fe₂O₃, and MnO₂ [9, 11]. During high-temperature sintering, these oxides react with alumina or form secondary oxide phases. In particular, changes in the d-orbital electronic states of the mixed oxides lead to absorption across the visible spectrum, producing a black color [12].

Bang et al. [6, 8, 9] reported that black alumina containing TiO₂, Fe₂O₃, and MnO₂ exhibited a reflectance below 8% with excellent densification. They also demonstrated that the electrical and optical properties of alumina strongly depend on additive composition and sintering atmosphere. Among these additives, MnO₂ acted as an effective blackening agent, and XRD analysis confirmed the presence of Mn–Al spinel phases as well as crystalline TiO₂ and Fe₂O₃. The resulting ceramics exhibited a resistivity of ~10¹⁰ Ω·cm, showing potential for LCD lithography applications where electrostatic suppression is required.

Black alumina generally exhibits liquid-phase sintering behavior due to the influence of additives. Furthermore, the granulation of mixed powders for powder pressing significantly affects microstructural homogeneity and densification behavior [13, 15]. In this study, alumina was mixed with several transition-metal oxides, mainly Co₂O₃ and TiO₂, to fabricate black alumina ceramics with low reflectivity at sintering temperatures below 1400 °C. Co₂O₃, with its low melting point, was used to promote liquid-phase sintering [16, 17], while TiO₂ was expected to be useful for resistivity control after subsequent reduction heat treatment. Other additives, such as Fe₂O₃ and MnO₂, can enhance the color depth and uniformity of black alumina, and when combined in specific ratios, they can also increase the sintering density and mechanical strength. Special attention was given to the influence of powder granulation on sintering behavior and final properties, aiming to achieve good densification at sintering temperatures below 1400 °C. The prepared black alumina powders, containing Co₂O₃ and TiO₂ as major additives, were granulated, compacted, and sintered. The effects on sintered density, microstructure, and mechanical properties were systematically investigated.

Preparation of black alumina granules

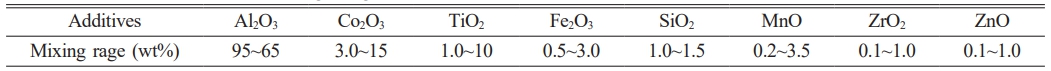

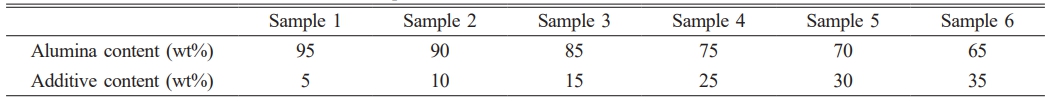

Commercial alumina powder (ALG-ISH, average particle size: 500 nm, purity: 99.8%, Daehan Ceramics, Korea) was used as the starting material. To induce black coloration and promote densification via liquid-phase sintering, various transition-metal oxides were employed as additives: Co₂O₃ (Umicore, 95%), TiO₂ (Samchun, 98.5%), Fe₂O₃ (Duksan, 96%), SiO₂ (Daejung, 99%), MnO (Sigma Aldrich, 99%), ZrO₂ (Daejung, 99%), and ZnO (Daejung, 99%). The mixing ranges are summarized in Table 1, and the compositions of the six experimental samples are listed in Table 2.

The mixed powders were wet-milled with zirconia balls (5 mm in diameter) in distilled water at 60 rpm for 12 h. The resulting slurry was dried at 80 °C, passed through a 240-mesh screen, and homogenized. For spray drying, the powders were dispersed in isopropyl alcohol (IPA) with the addition of 2 wt% polyvinyl butyral (PVB) as a binder and 1 wt% polyethylene glycol (PEG) as a plasticizer [13, 18, 19]. An antifoaming agent (0.001 wt% relative to the powder) was also added. The slurry was further ball-milled for 12 h, and the pH was adjusted to 10.5-10.8 using a dispersant to maintain a viscosity below 20 cPs. The viscosity of a slurry indicates the degree of particle dispersion, and when solid particles exhibit a certain level of agglomeration, it can prevent the formation of hollow granules [20]. Spray granulation was carried out using a disk-type spray dryer at a disk speed of 5000 rpm and a vacuum pump speed of 50 rpm to produce black alumina granules.

The granules were uniaxially pressed at 1 ton/cm² into disk-shaped compacts (24 mm in diameter). For comparison, compacts were also prepared directly from mixed powders without granulation. The green bodies were sintered in air at 1200-1450 °C for 1 h with a heating rate of 3 °C/min, followed by furnace cooling to obtain black alumina ceramics.

Characterization

The microstructures of the granules, green compacts, and sintered specimens were examined by field-emission scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM, JSM-7100F, JEOL, Japan). The bulk densities of the sintered bodies were determined by the Archimedes method. Phase analysis was carried out by X-ray diffraction (XRD, DMAX 2200, Rigaku, Japan) with Cu Kα radiation at 40 kV and 30 mA. Vickers hardness was measured on polished specimens (grinding with SiC papers #160–2000and subsequently mirror polished) using a microhardness tester (ZHμ-A, INDENTEC, U.K.) under a 1 kgf load. The reported values represent the average of five indentations. Optical reflectivity was evaluated in the visible range (380-780 nm) using a high-resolution UV–VIS–NIR spectrophotometer (CARY 500 SCAN, Varian).

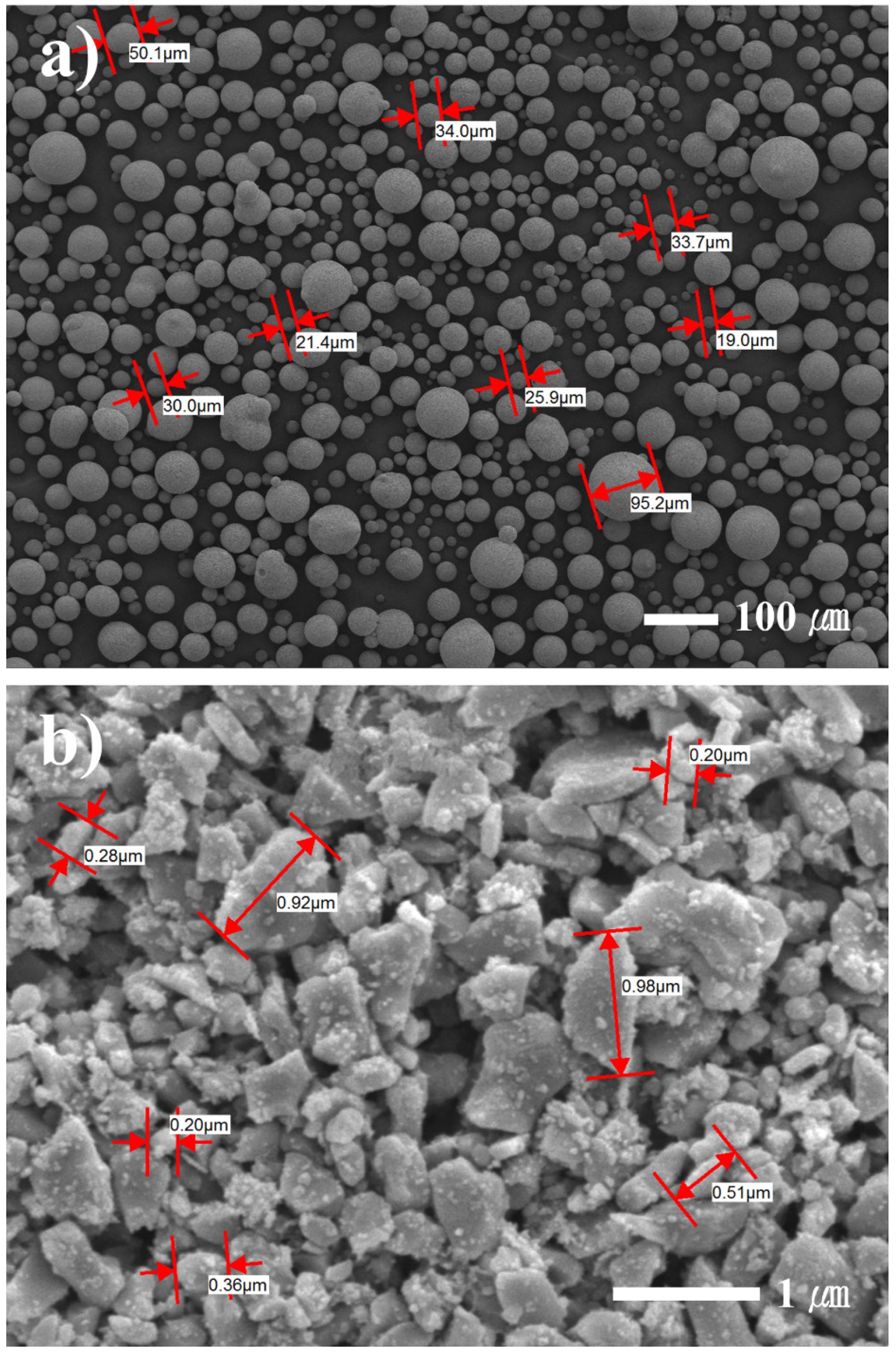

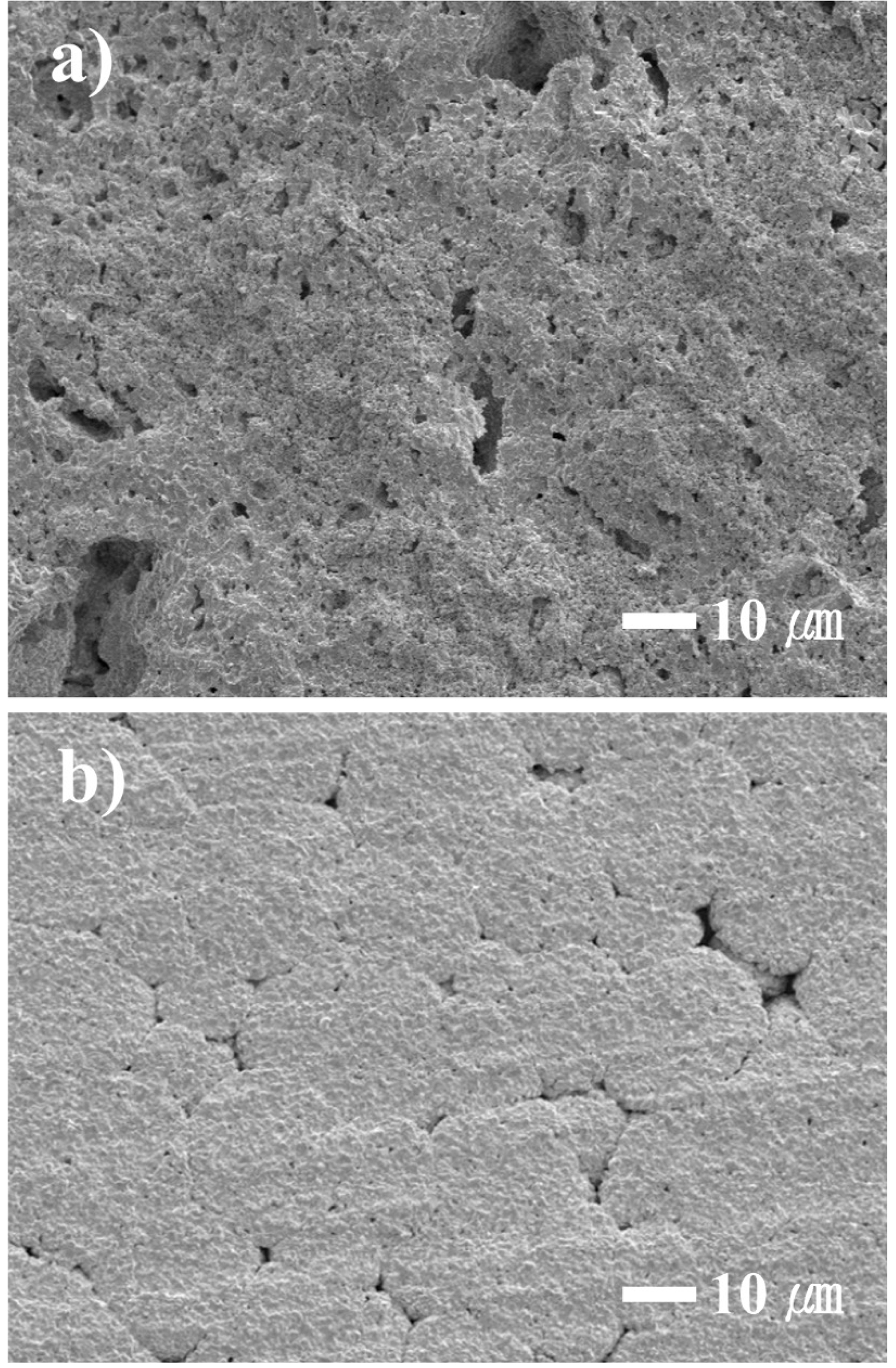

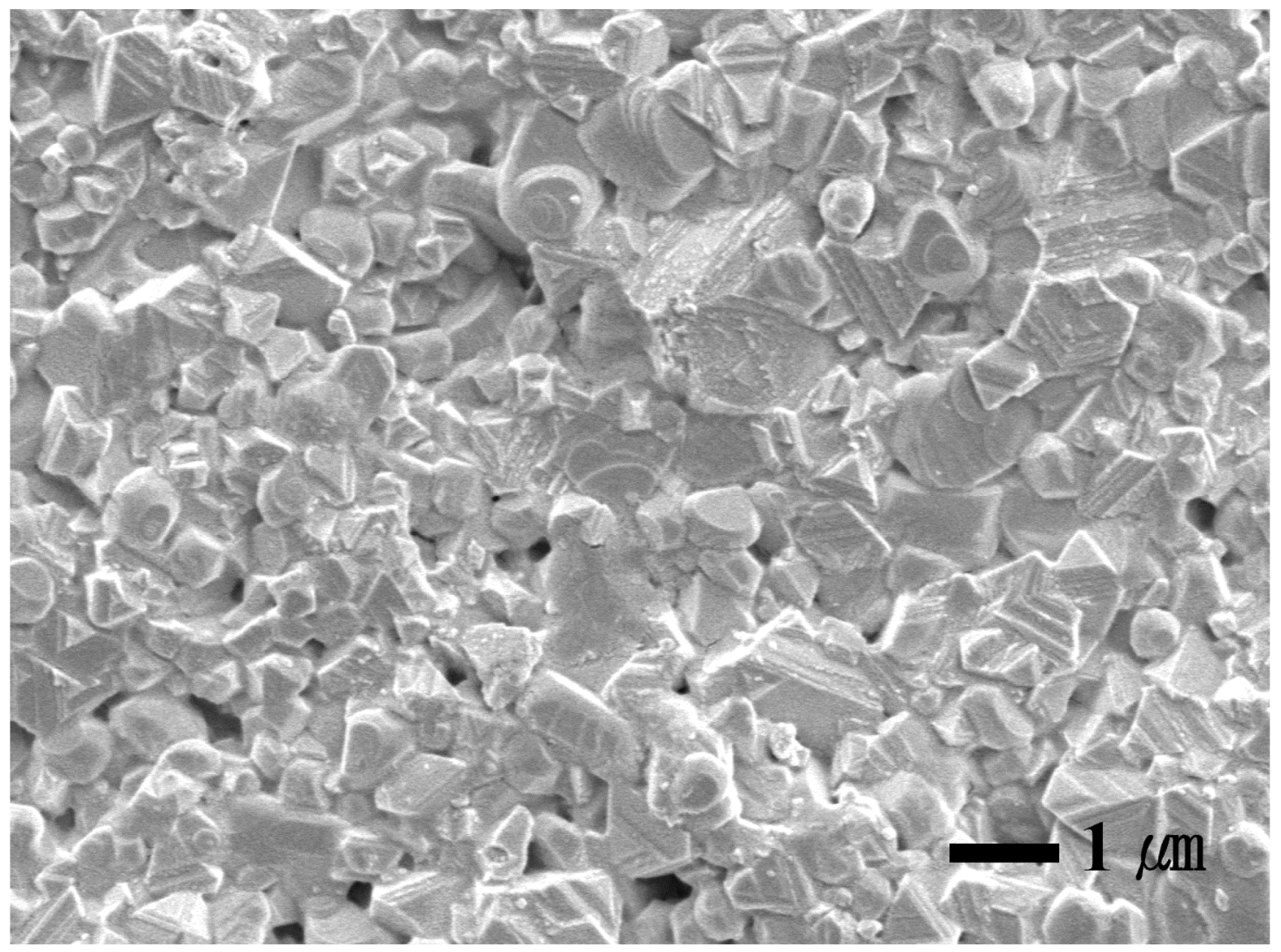

The microstructure of the black alumina granules is shown in Fig. 1. The granules exhibited spherical morphology with particle sizes ranging from 19.0 to 95.2 μm along with a small fraction of fractured particles. High-magnification observations revealed submicron particles inside the granules, originating from the starting alumina powder of 500 nm and various added oxide additives, which primarily contributed to a broad particle size distribution. The effect of granulation on densification was examined using sample 6 sintered at 1200 °C, as shown in Fig. 2. While compacts prepared without granulation contained large pores resulting from inhomogeneous packing, those prepared from granulated powders exhibited higher green density and traces of granule boundaries, indicating more uniform packing and improved particle rearrangement. This improvement can be attributed to more homogeneous powder packing, enhanced particle sliding induced by plasticizer during pressing, and reduced agglomeration [21].

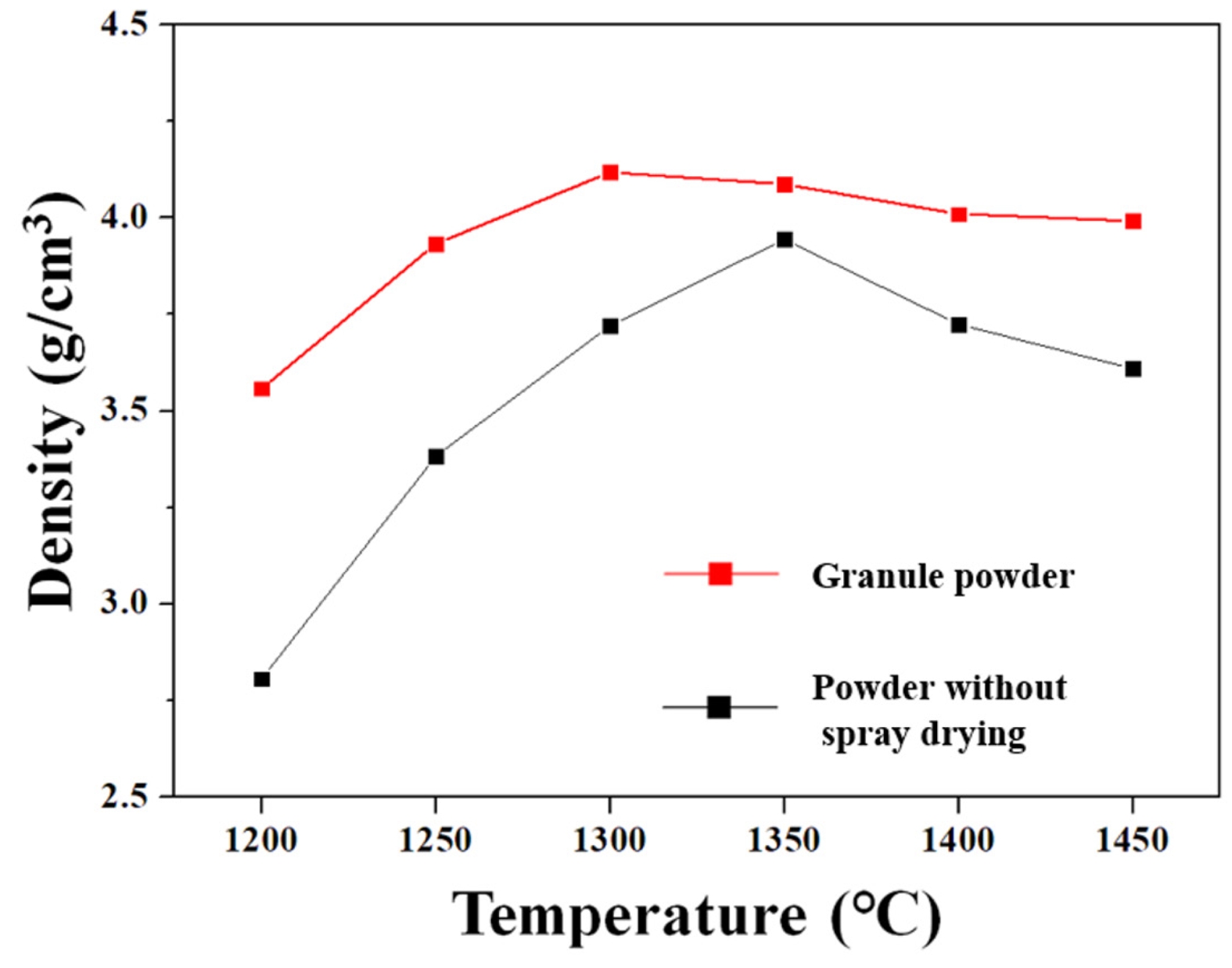

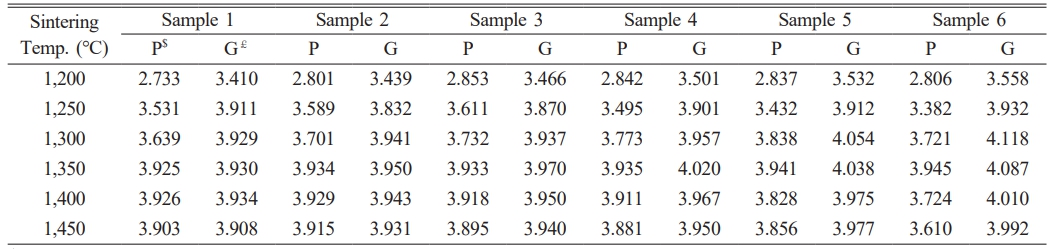

The densification behavior of sample 6 at different sintering temperatures is shown in Fig. 3. The density increased with temperature and reached a maximum around at 1300-1350 °C, followed by a decrease at higher temperatures due to the formation of glassy phases and secondary compounds. Granulated powders exhibited higher densification than non-granulated powders at all temperatures, with the maximum observed at 1300 °C. This was attributed to extensive particle rearrangement, a primary mechanism of liquid phase sintering, enabled the higher green density [14, 16, 22], in contrast, compacts prepared from non-granulated powders achieved their highest density at 1350 °C due to delayed pore elimination. In the case of granules, the granules are broken and compacted under pressure. In this process, the particle size distribution of the granules is also crucial for achieving uniformity in powder filling in mold; a certain degree of variation in particle size distribution is actually more efficient for the filling process than having uniformly sized granules [23]. Furthermore, the distribution of liquid materials tends to be relatively uniform in granules through the slurry preparation process, which is believed to facilitate densification through particle rearrangement during the liquid phase sintering. Table 3 summarizes the sintered densities of all compositions, which followed similar trends. Even sample 1, the highest alumina content, reached nearly full densification at 1350 °C due to the low eutectic temperature of the additives. At this temperature, water absorption values were below 0.1% for all samples, confirming nearly complete densification. However, density values were not directly compared with each other because of their differences in additive content. In sample 6, however, density decreased above 1350 °C because excessive formation oflow-viscosity liquid suppressed solid-state particle coalescence [24]. The difference between granulated and non-granulated powders diminished with increasing sintering temperature, particularly in samples with higher alumina content. This suggests that green density plays a dominant role in liquid phase sintering below 1350 °C, whereas densification above this temperature is governed mainly by solid state particle coalescence [14].

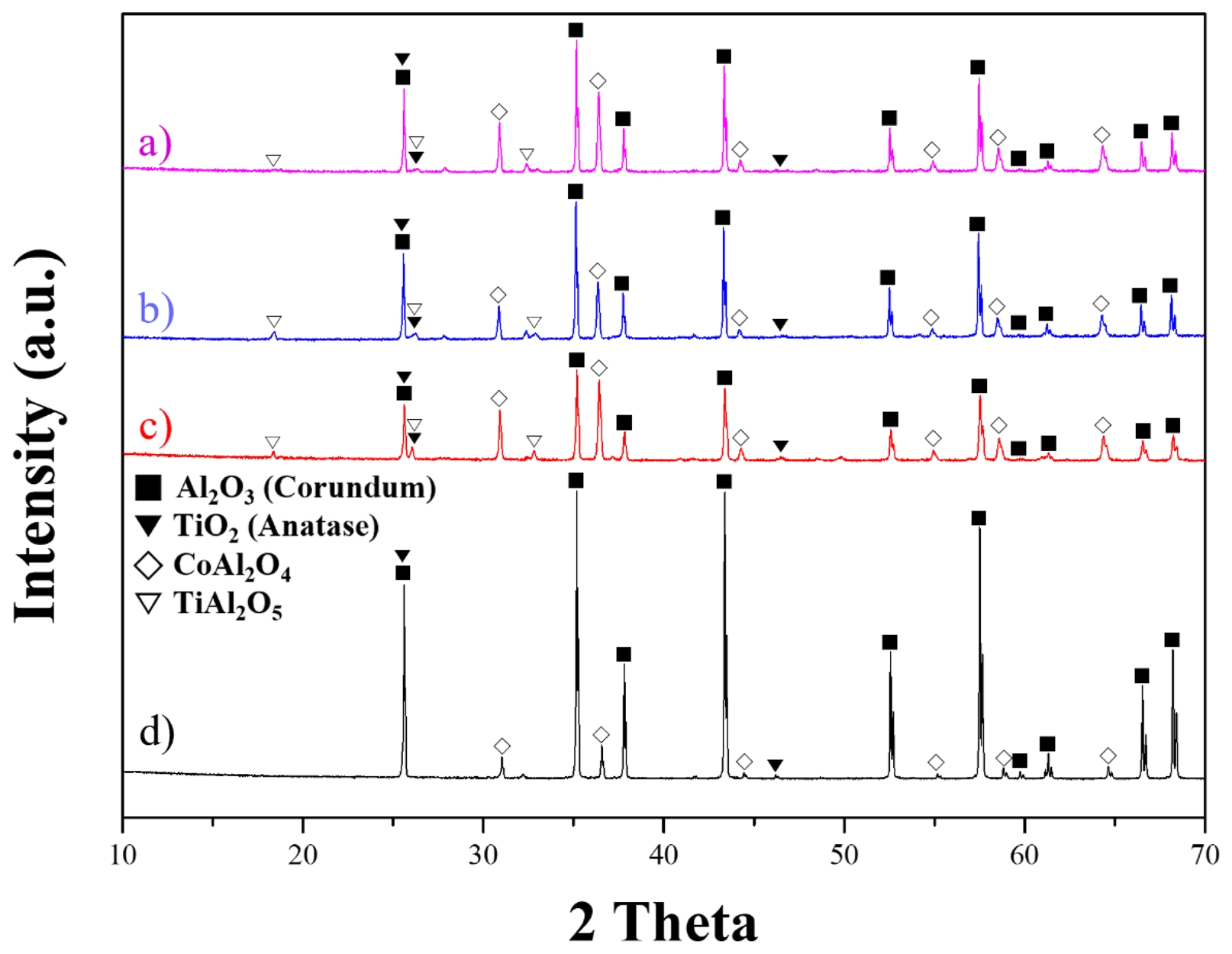

Phase evolution during sintering was investigated by XRD, as shown in Fig. 4. For sample 6, CoAl₂O₄ was detected together with Al₂O₃ at 1300 °C, and TiAl₂O₅ appeared at higher temperatures, with its peak intensity increasing as the sintering temperature rose. The melting of Co₂O₃ below 1000 °C promoted liquid-phase sintering, leading to the formation of CoAl₂O₄ during particle rearrangement [16, 25]. TiAl₂O₅ began to form above 1280 °C, consistent with phase-equilibria data [25]. Fe₂O₃ and MnO also contributed to liquid-phase formation and black coloration, however, their characteristic XRD peaks were not observed. In sample 1, which contained 95 wt% alumina, only Al₂O₃ with a small amount of CoAl₂O₄ was detected after sintering at 1350 °C.

The fracture surface of sample 6 sintered at 1350 °C with granulated powders is shown in Fig. 5. The grain size remained comparable to that of the starting powders, indicating that densification was primarily governed by capillary-driven particle rearrangement in the liquid phase rather than by significant grain growth [14, 22].

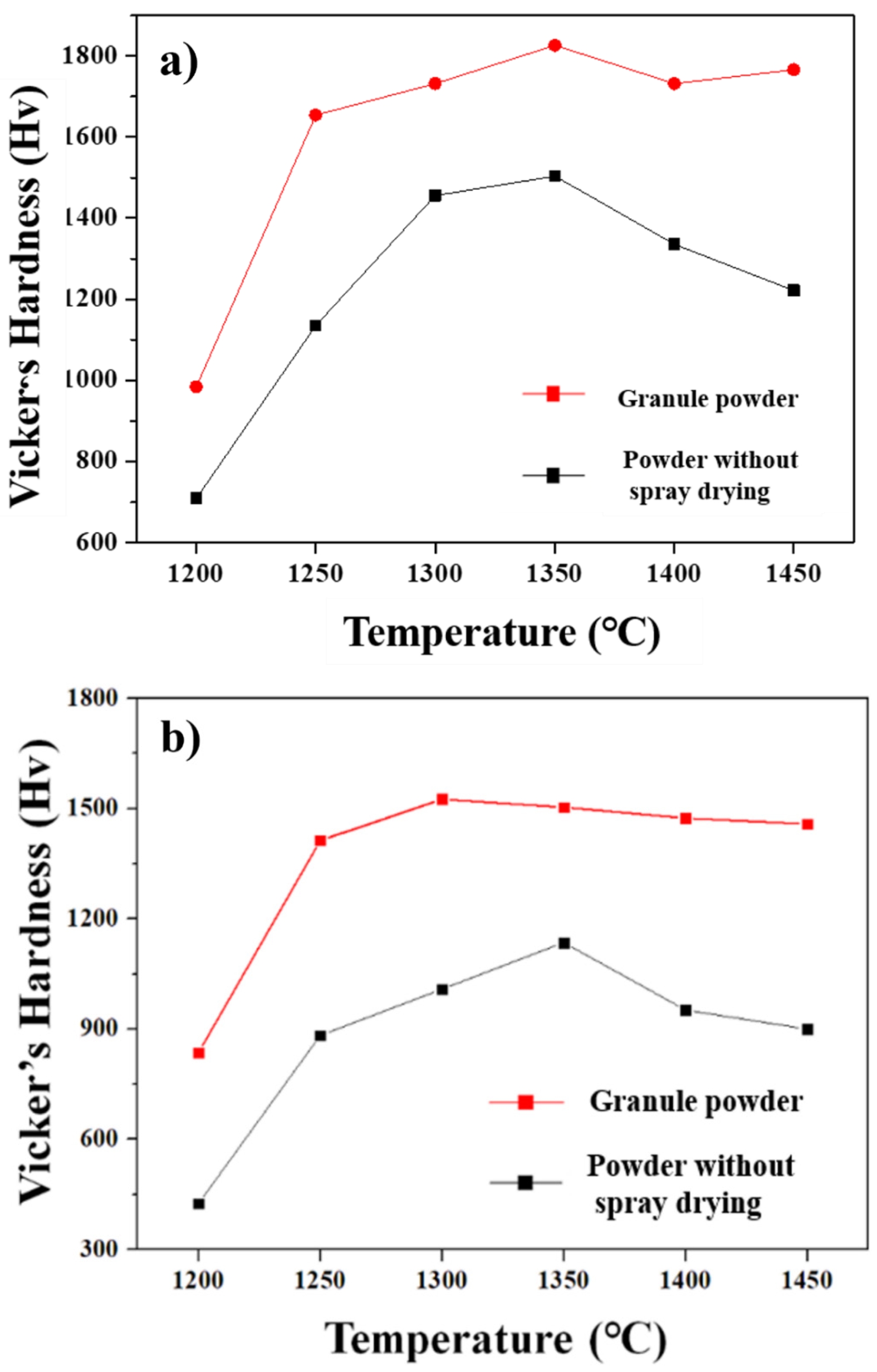

The hardness results for samples 1 and 6 are presented in Fig. 6. Hardness is strongly influenced by porosity and grain size [1]. Sample 1, with the highest alumina content, exhibited higher hardness due to the smaller amount of liquid phase. When granulated powders were used, hardness reached a maximum of ~1800 Hv at 1350 °C, which is comparable to that of commercial 96% alumina ceramics. Sample 6 also showed improved hardness with granulation. However, hardness decreased above 1400 °C due to the formation of glassy phases, secondary compounds, and grain growth. In general, smaller grains provide higher hardness by increasing grain boundary area and hindering dislocation motion [26, 27]. Although hardness decreased with increasing additive content, sample 6 prepared from granulated powders still reached ~1500 Hv at 1300 °C, confirming the feasibility of producing dense black alumina with relatively high hardness.

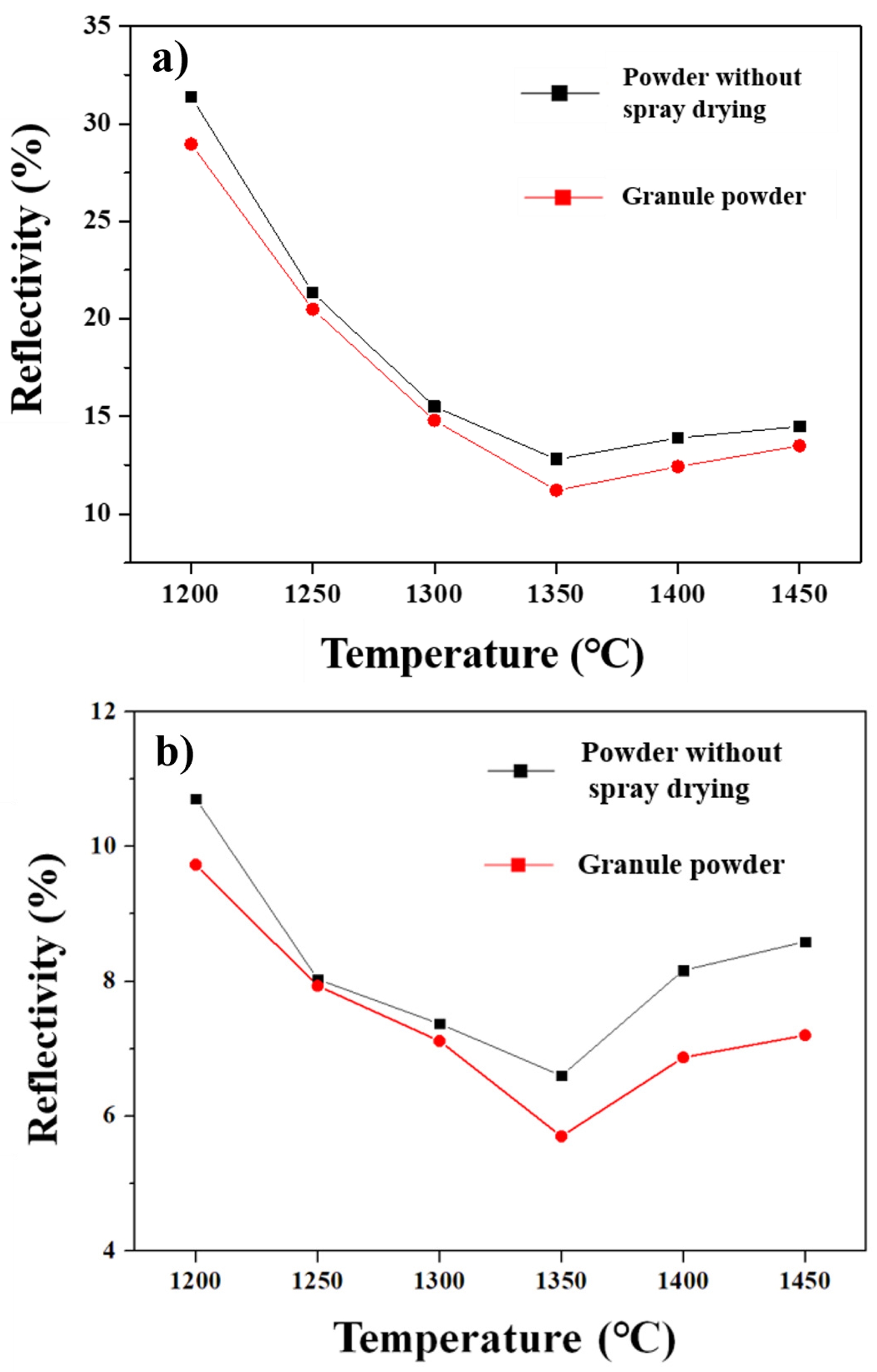

The reflectivity of samples 1 and 6 is shown in Fig. 7. Reflectivity decreased up to 1350 °C but increased again at higher temperatures, which was speculated to result from the volatilization of low-melting additives, such as Co₂O₃, and the development of crystalline phases(CoAl2O4, TiAl2O5) at higher temperatures (Fig. 4) [28]. Sample 6 exhibited lower reflectivity than sample 1 due to its higher additive content. All samples showed values below 10%, satisfying the requirements for black alumina used in semiconductor processes. Granulated powders also consistently exhibited lower reflectivity than non-granulated powders at all sintering temperatures, which is related to their lower porosity and higher densification [6].

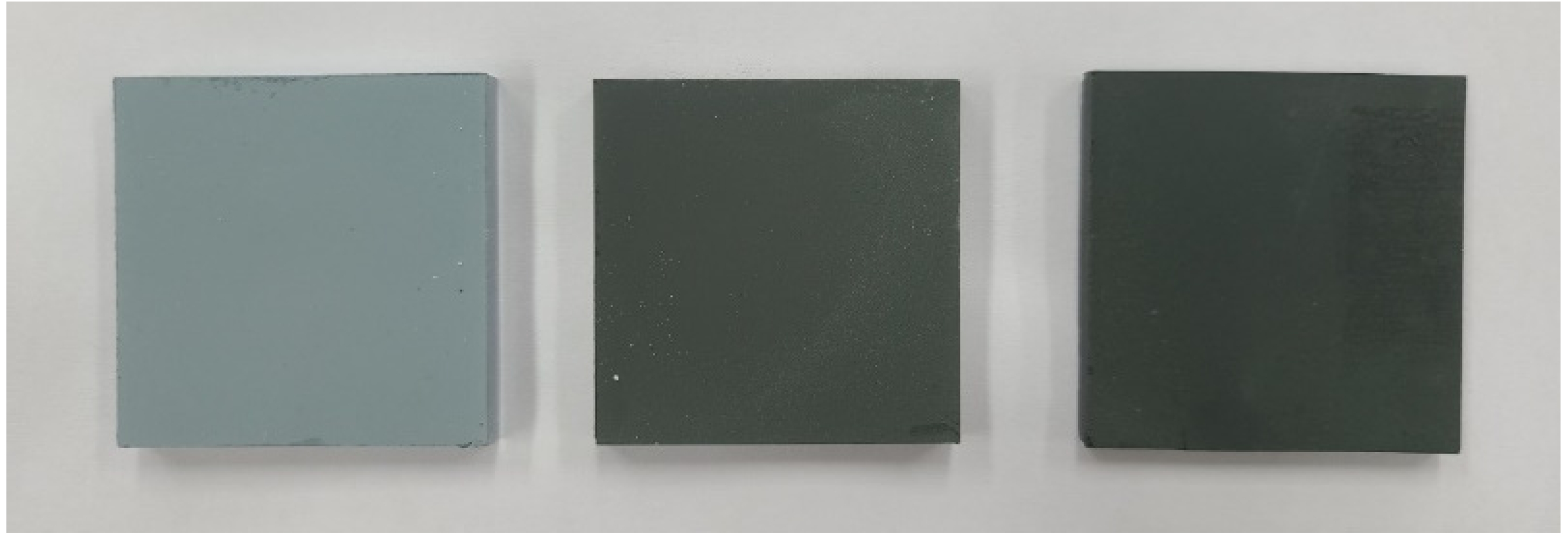

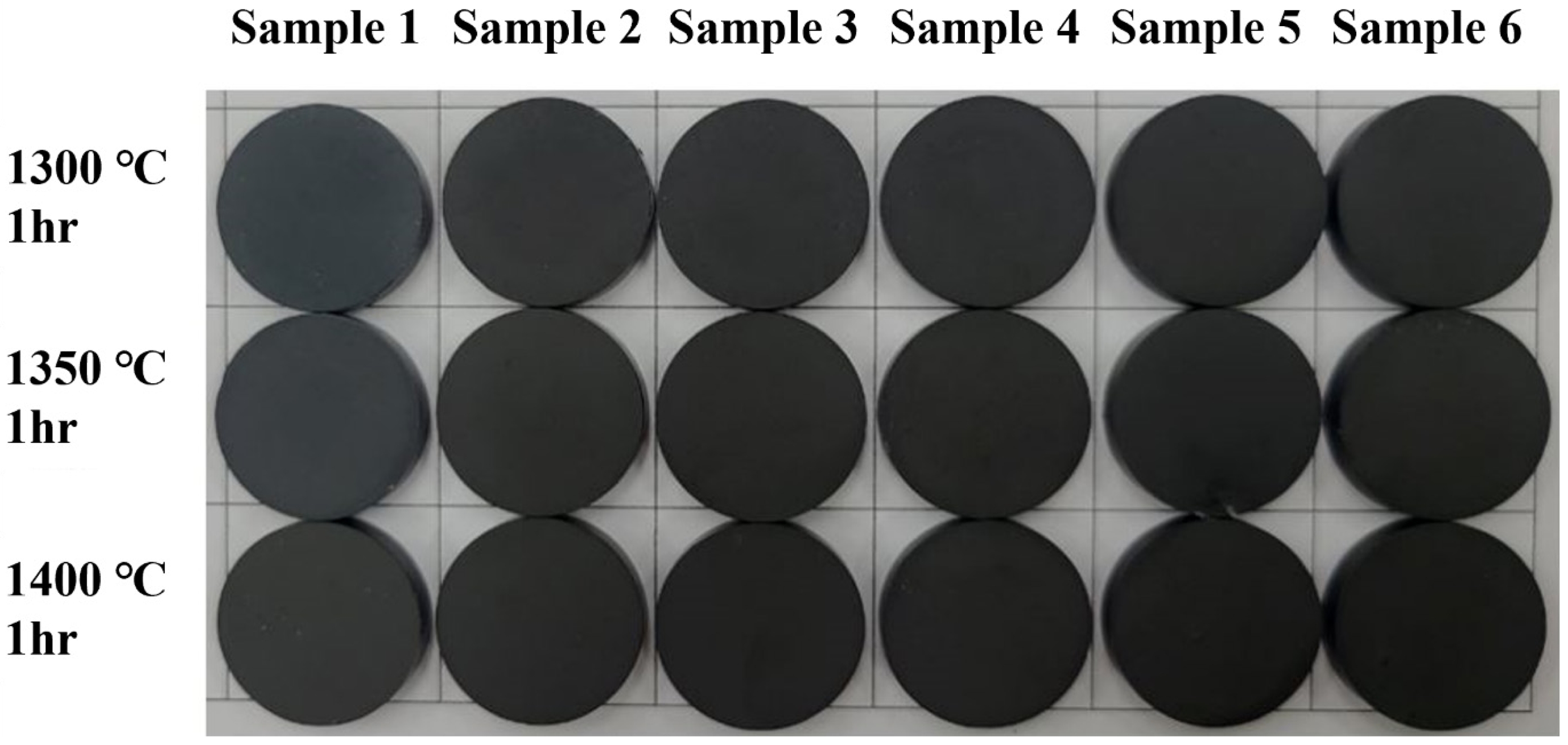

The effect of additive content on color development is shown in Figs. 8 and 9. At 1200 °C (Fig. 8), sample 1 with a low additive content exhibited a greenish tint due to cobalt, whereas sample 6 already showed a black appearance even before achieving full densification. This suggests that black coloration originates from the reactions between the additives and alumina, or from the formation of secondary oxide phases that absorb visible light [6]. At higher temperatures (Fig. 9), all samples exhibited uniform black coloration, and by 1400 °C the black color was clearly visible across all compositions.

|

Fig. 1 SEM micrographs of black alumina granules (a) ×100 and (b) ×10,000. |

|

Fig. 2 SEM micrographs of sample 6 (35 wt% additive content) black alumina sintered at 1200 °C, compacted with (a) powder without spray drying and (b) granule powder. |

|

Fig. 3 Densification behavior of sample 6 (35 wt% additive content) black alumina sintered at various temperatures according to different starting powder type. |

|

Fig. 4 XRD patterns of sample 6 (35 wt% additive content) and sample 1 (5 wt% additive content) sintered at 1300 °C-1400 °C. (a) sample 6, 1300 °C, (b) sample 6, 1350 °C, (c) sample 6, 1400 °C and (d) sample 1, 1350 °C. |

|

Fig. 5 SEM micrographs of sample 6 (35 wt% additive content) black alumina sintered at 1350 °C, prepared with granule powder. |

|

Fig. 6 Measured hardness of black alumina sintered at various temperatures according to different starting powder type of (a) sample 1 (5 wt% additive content) and (b) sample 6 (35 wt% additive content). The black alumina prepared from granules exhibited improved hardness at all sintering temperatures, with a lesser reduction in hardness observed in samples sintered at higher temperatures. |

|

Fig. 7 Measured Reflectivity of black alumina sintered at various temperatures according to different starting powder type of (a) sample 1 (5 wt% additive content) and (b) sample 6 (35 wt% additive content). The black alumina prepared from granules exhibited decreased reflectivity at all sintering temperatures. |

|

Fig. 8 Photographs of black alumina sintered at 1200 °C, prepared with granule powder (from left : sample 1, 3, 6) |

|

Fig. 9 Photographs of black alumina sintered at 1300-1400 °C according to additive content, prepared with granule powder. |

|

Table 3 Sintered Density of Each Samples at Different Sintering Temperature (Unit : g/cm3 ) |

$P : Powder without spray drying |

Black alumina ceramics were successfully fabricated by granulating mixtures of alumina and transition-metal oxide additives, resulting in enhanced densification via liquid-phase sintering and improved overall properties. The use of granulated powders provided higher packing density and better compactability, which facilitated particle rearrangement during sintering and led to increased hardness and reduced reflectivity. The addition of Co₂O₃ promoted liquid-phase formation at relatively low temperatures, enabling nearly full densification and stable black coloration at 1300-1350 °C. Dense black alumina ceramics with hardness values comparable to those of commercial alumina and reflectivity below 10% were obtained over a wide additive range (5-35 wt%). These findings demonstrate a viable processing route for producing black alumina with controlled optical and mechanical properties at relatively low sintering temperatures. Furthermore, the results confirmed that granulation is an essential step for commercial dry-processing applications of black alumina, and the material is expected to find application in semiconductor and display lithography processes, where low reflectivity and electrostatic control are required. Future work will focus on resistivity control through TiO₂ addition combined with reduction heat treatment.

This research was supported by the Regional Innovation System and Education (RISE) program through the Jeollanamdo RISE center, funded by the Ministry of Education (MOE) and the Jeollanamdo, Republic of Korea (2025-RISE-14-001).

- 1. R.G. Munro, J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 80[8] (1997) 1919-1928.

-

- 2. O.L. Ighodaro and O.I. Okoli, Int. J. Appl. Ceram. Technol. 5[3] (2008) 313-323.

-

- 3. S. Yang, S. Yang, Y. Zhu, L. Fan, and M. Zhang, J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 42 (2022) 202-206.

-

- 4. X. He, T. Feng, Y. Cheng, P. Hu, Z. Le, Z. Liu, and Y. Cheng, J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 106[11] (2023) 7019-7042.

-

- 5. J. Du, X. Yi, M. Li, and K. Peng, J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 40 (2020) 6218-6222.

-

- 6. I.H. Bang, K.O. Kim, and S.J. Lee, J. Ceram. Process. Res. 15[6] (2014) 525-529.

-

- 7. J. Kim, J.H. Ha, J. Lee, and I.H. Song, J. Korean Ceram. Soc. 53[5] (2016) 548-556.

-

- 8. J. Kim, J.H. Ha, J. Lee, and I.H. Song, J. Korean Ceram. Soc. 54[4] (2017) 331-339.

-

- 9. D.H.A. Besisa, E.M.M. Ewais, H.H. Mohamed, N. Besisa, and E.A. Mohamed, Ceram. Int. 49 (2023) 20429-20436.

-

- 10. J. Wu, Y. Liu, X. Xu, S. Liu, M. Li, and Y. Yin, Ceram. Int. 49 (2023) 10765-10773.

-

- 11. S.M. Kwa, S. Ramesh, L.T. Bang, Y.H. Wong, W.J.K. Chew, C.Y. Tan, J. Purbolaksono, H. Misran, and W.D. Teng, J. Ceram. Process. Res. 16[2] (2015) 193-198.

-

- 12. X. Zhang, Y. Xu, Z. Li, M. Liu, T. Du, R. He, and G. Ma, Metals 13[12] (2023) 1949.

-

- 13. P. Höhne, B. Mieller, and T. Rabe, J. Ceram. Sci. Technol. 9[3] (2018) 327-336.

-

- 14. R.M. German, P. Suri, and S.J. Park, J. Mater. Sci. 44 (2009) 1-39.

-

- 15. H. Kong, J.K. Lee, and S.J. Lee, J. Ceram. Process. Res. 18[10] (2017) 726-730.

-

- 16. B.H. Oh, T.G. Yoon, H. Kong, N.I. Kim, and S.J. Lee, J. Korean Cryst. Growth Cryst. Technol. 30[4] (2020) 150-155.

- 17. Y.N. Lee, H. Nam, and K.W. Nam, J. Ceram. Process. Res. 21[1] (2020) 99-102.

-

- 18. W. Liu, W. Zhang, J. Li, D. Zhang, and Y. Pan, Ceram. Int. 38 (2012) 259-264.

-

- 19. K. Rajeswari, S. Chaitanya, P. Biswas, M.B. Suresh, Y.S. Rao, and R. Johnson, J. Ceram. Process. Res. 16[1] (2015) 24-31.

-

- 20. T. Mori, H. Imazeki, and K. Tsuchiya, Ceram. Int. 43[14] (2017) 11170-11176

-

- 21. W. Liu and Z. Xie, Sci. Sinter. 47 (2015) 279-288.

-

- 22. W. Dong, H. Jain, and M.P. Harmer, J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 88[7] (2005) 1702-1707.

-

- 23. W.C. Du, J. Roa, J.H. Hong, Y.W. Liu, Z.J. Pei, and C. Ma, J. Manuf. Sci. Eng-Trans ASME, 143[9] (2021) 091002.

-

- 24. L. He, N. Huang, D. Lu, P. Sheng, and W. Zou, Crystals 13[7] (2023) 1099.

-

- 25. I.J. Kim and L.G. Gauckler, J. Ceram. Sci. Technol. 3[2] (2012) 49-60.

- 26. L.L. Sartinska, Powders 4[3] (2025) 18.

-

- 27. S. Kondo, T. Mitsuma, N. Shibata, and Y. Ikuhara, Sci. Adv. 2[11] (2016) e1501926.

-

- 28. A.M. Abyzov, Glass Ceram. 75[7-8] (2018) 293-302.

-

This Article

This Article

-

2025; 26(6): 1048-1054

Published on Dec 31, 2025

- 10.36410/jcpr.2025.26.6.1048

- Received on Sep 13, 2025

- Revised on Nov 24, 2025

- Accepted on Nov 24, 2025

Services

Services

- Abstract

introduction

experimental procedure

results and discussion

conclusions

- Acknowledgements

- References

- Full Text PDF

Shared

Correspondence to

Correspondence to

- Sang-Jin Lee

-

bDepartment of Advanced Materials Science and Engineering, Mokpo National University, Muan 58554, Republic of Korea

dResearch Institute of Ceramic Industry and Technology, Mokpo National University, Muan 58554, Republic of Korea

Tel : +82-61-450-2493 Fax: +82-61-450-2498 - E-mail: lee@mokpo.ac.kr

Copyright 2019 International Orgranization for Ceramic Processing. All rights reserved.

Copyright 2019 International Orgranization for Ceramic Processing. All rights reserved.