- Green synthesis and physical-biological evaluation of boron-doped CuO nanocomposites via Aronia extracts

Esen Çakmaka,*, Ayça Tanriverdi̇b and Saniye Tekerekc

aDepartment of Bioengineering and Sciences, Graduate School of Natural and Applied Sciences, Kahramanmraş Sütcü Imam University, Kahramanmaras, Turkey

bDepartment of Material Science and Engineering, Graduate School of Natural and Applied Sciences, Kahramanmaraş Sütcü Imam University, Kahramanmaraş, TurkeyThis article is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

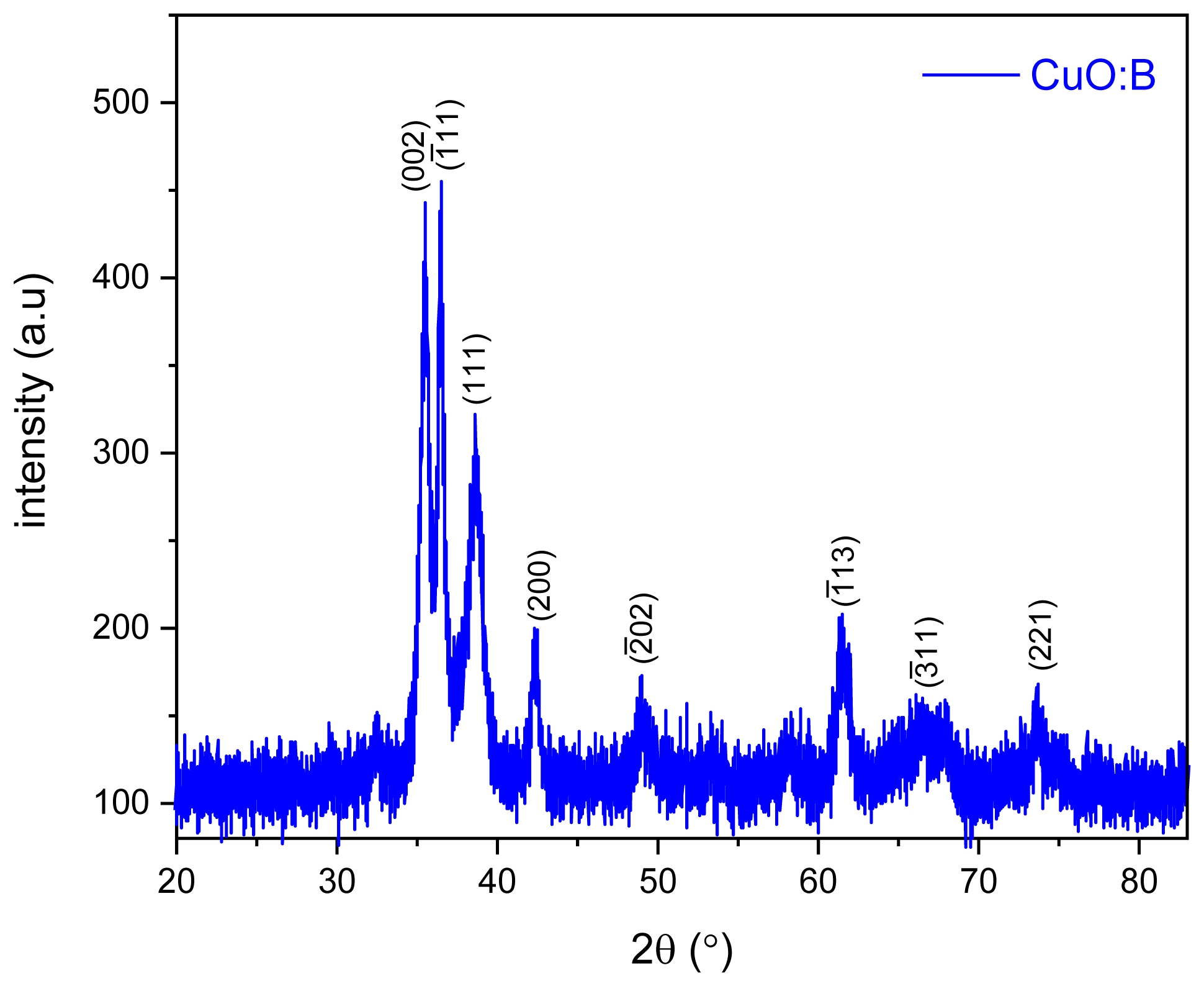

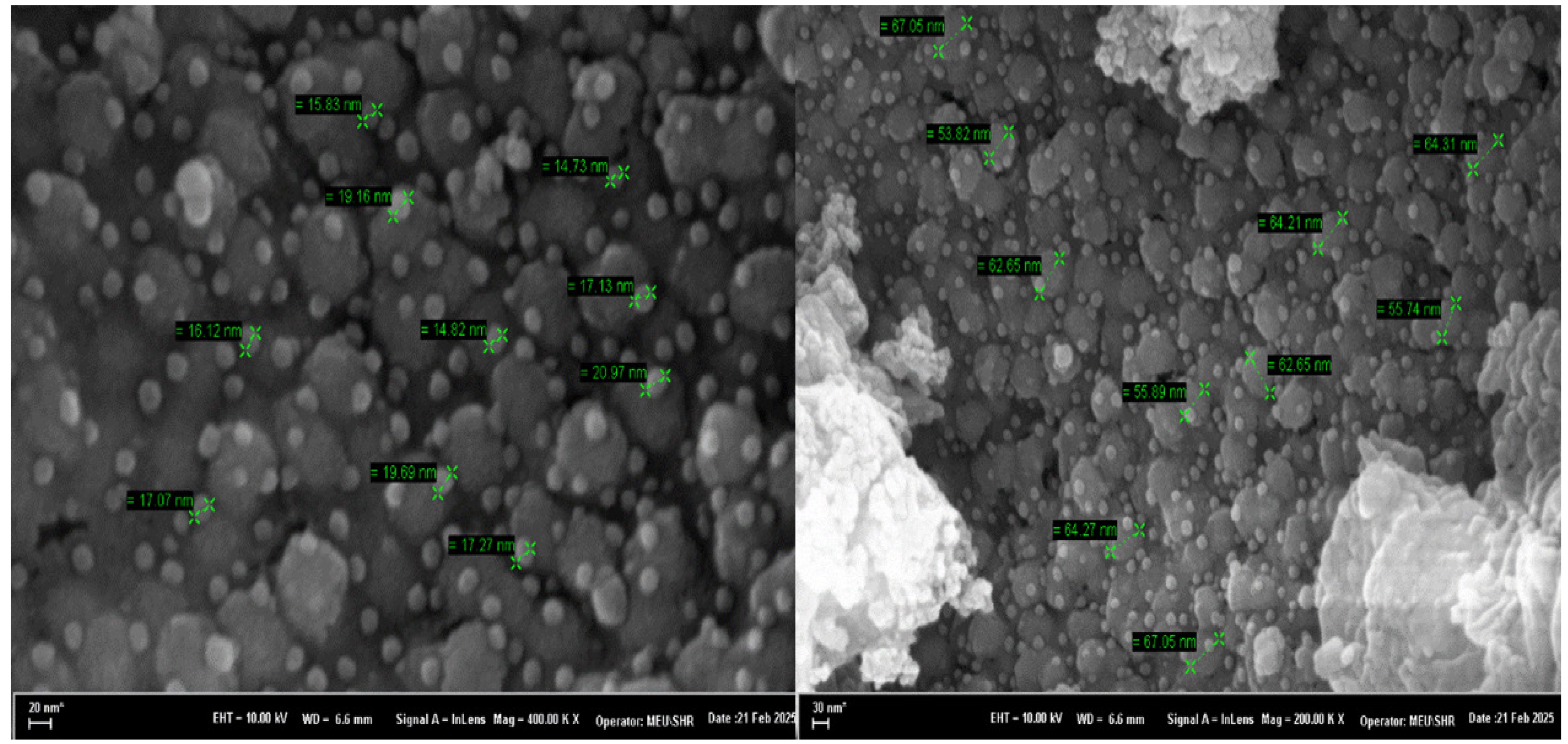

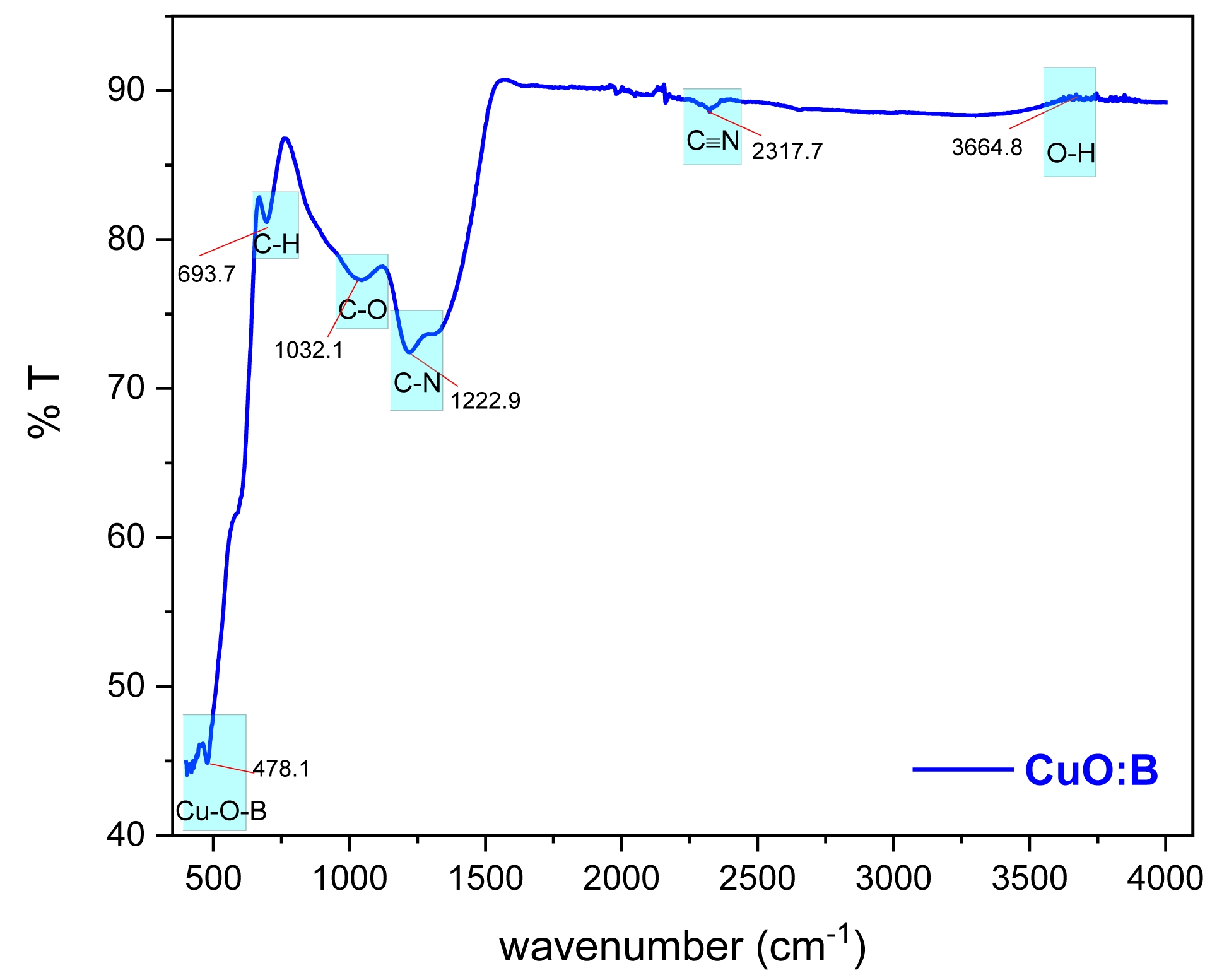

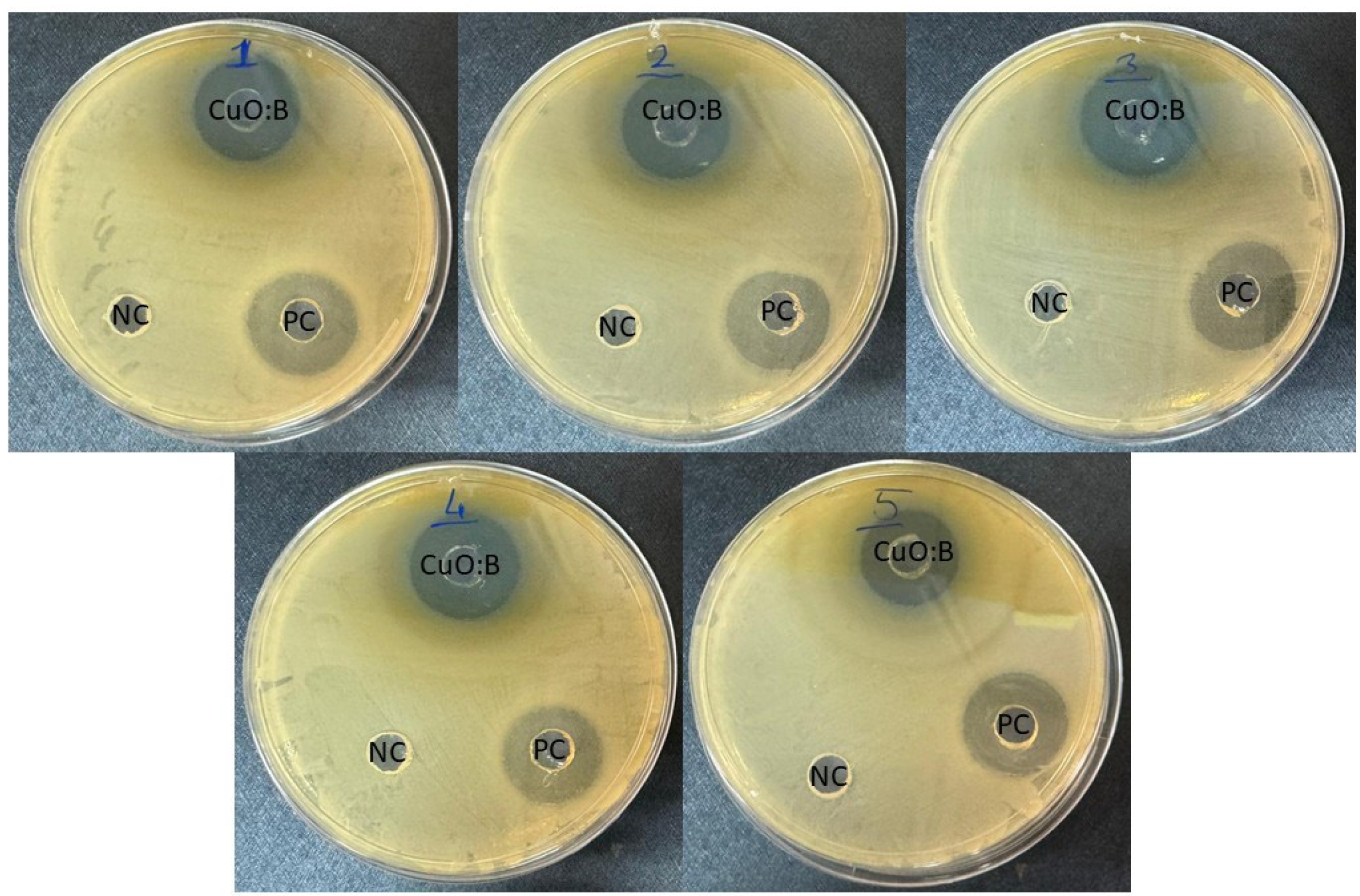

In this study, boron-doped copper oxide (CuO:B) nanocomposites were synthesized via a green method using Aronia melanocarpa fruit extract as a natural reducing and stabilizing agent. The structural and morphological characteristics of the nanocomposites were analyzed using X-ray diffraction (XRD), scanning electron microscopy (SEM), and Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR). The biosynthesized CuO:B nanocomposites were further evaluated for their antimicrobial, antioxidant, and anticancer activities. XRD analysis confirmed a monoclinic crystal structure, indicating that boron doping did not alter the CuO phase. SEM images revealed a uniform distribution of nearly spherical nanoparticles with sizes ranging from 15 to 67 nm. FTIR spectra exhibited a characteristic Cu-O vibration band at 478 cm⁻¹. The nanocomposites demonstrated strong antimicrobial activity against pathogenic strains (Enterococcus faecalis, Staphylococcus aureus, Salmonella enteritidis, Enterobacter aerogenes, and Escherichia coli), along with notable antioxidant activity (IC₅₀ = 210 µg/mL). Anticancer assays revealed that CuO:B nanocomposites induced early apoptosis in A549 cancer cells (92.45%) with an IC₅₀ value of 30.57 µg/mL. These findings suggest that CuO:B nanocomposites synthesized from A. melanocarpa exhibit significant antimicrobial, antioxidant, and anticancer activities, indicating their potential as therapeutic candidates for biomedical applications supported by further studies such as in vitro and in vivo studies.

Keywords: Aronia melanocarpa, Boron-doped copper oxide, Antimicrobial activities, Antioxidant activities, Anticancer activities.

In recent years, metal oxide nanomaterials have been the focus of interest in various fields such as physics, chemistry, biology, food, textile and medicine due to their superior properties. Their size range of 1-100 nm has given these materials unique physical, chemical and biological properties [1]. A high surface-to-volume ratio renders these nanoparticles highly reactive and functional, enabling their use as catalysts, drug carriers, sensors, or coating materials in diverse applications [2]. Among these metal oxide nanoparticles, copper oxide nanoparticles (CuO NPs) are among the most extensively studied due to their broad range of biological activities. Copper (Cu) is an essential trace element in cells and plays a crucial role in various physiological processes, including enzyme activity, antioxidant defense, and nervous system function [3, 4]. When combined with nanobiotechnology, these properties of copper enable more stable and targeted biological interactions.

CuO NPs are generally synthesized using physical, chemical, or biological methods. Among these, each with its own limitations depending on the intended application, biological methods are particularly preferred in biomedical fields due to their advantages, including environmental friendliness, simplicity, cost-effectiveness, reliability, and sustainability [4, 45]. In biological synthesis methods, plants, bacteria, fungi, or algae are employed as reducing and capping agents. During the synthesis process, plant and microbial extracts facilitate the reduction of Cu²⁺ ions and promote the formation of stable CuO NPs. Furthermore, these biomolecules coat the surface of the nanoparticles, thereby enhancing their biocompatibility [1]. Many CuO NPs have been synthesized using this approach, commonly referred to as the green synthesis method. Various studies have demonstrated the beneficial effects of CuO NPs in a range of biological processes, including antimicrobial, antioxidant, antibiofilm, anticancer, antidiabetic, and apoptotic activities, highlighting their potential as therapeutic agents [5-7].

Boron is recognized as a prebiotic component and serves as an essential trace element in plants, certain bacteria, fungi, and algae. It has been reported to exert beneficial effects on human health by supporting reproduction, growth, calcium and energy metabolism, bone formation, immune function, brain activity, and the regulation of certain steroid hormones [8]. Boron-containing compounds exhibit microbicidal effects by disrupting cell membrane structure, inhibiting enzyme activity, or inducing damage to proteins and DNA [9]. In addition, they have been reported to possess significant biological activities, including antibiofilm, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anticancer effects. Owing to these properties, boron-containing compounds hold considerable potential for applications in medical, biomedical, and pharmaceutical fields [10, 11]. However, despite the promising potential of boron-containing nanocomposites, research in this area remains scarce [12-15]. To date, only a few studies have explored the antimicrobial [16] and anticancer [17] effects of CuO nanocomposites synthesized using the green synthesis approach.

Aronia melanocarpa, a member of the Rosaceae family, is a perennial plant known for its medicinal use. This plant, abundant in phytocomponents, demonstrates a range of biological activities, with particularly notable antioxidant properties. In the literature, only silver and gold nanoparticles have been synthesized using A. melanocarpa, and the antimicrobial and antioxidant activities of these nanoparticles have been evaluated [18, 19]. In the present study, boron-doped CuO nanocomposites were synthesized using A. melanocarpa fruit extract for the first time, characterized, and their antimicrobial, antioxidant, and anticancer activities were evaluated. Research on the green synthesis of boron-containing CuO nanocomposites remains limited. This study represents the first documented use of A. melanocarpa in the production of CuO nanocomposites.

Plant Extraction

Aronia fruit samples were purchased commercially. After cleaning with deionized water (dH2O), the stems were removed and the samples (25 g) were crushed in a grinder. The samples were placed in 50 mL deionized water at 40 °C for 30 min using an ultrasonic bath. Then filtered on Whatman 1 filter paper.

Preparation of CuO:B NCs

To prepare CuO:B NC by green synthesis method, 64 g Copper(II) (Sigma) acetate hydrate in 30 mL deionized water and 2.5 g Boric acid (Merck) in 20 mL deionized water were kept separately in an ultrasonic bath at 40 °C for 30 min. The plant extract, copper acetate solution and boric acid solution were then combined and stirred overnight at 70 °C in a magnetic stirrer. Based on preliminary optimization studies, temperatures below 60°C resulted in incomplete precursor reduction, while temperatures above 80°C led to particle agglomeration. Similarly, reaction times shorter than 10 hours produced products with lower crystallinity. Therefore, the synthesis was performed at 70 °C for approximately 12 hours to achieve optimal particle stability and biological performance. The occurrence of color change is an indication that CuO:B NCs were produced. The produced NCs were washed after 15 min centrifugation (5000 rpm) and stored at +4 °C for further analyses. The synthesis procedure was repeated three times under identical experimental conditions.

Characterization of CuO:B NCs

X-ray Diffraction (XRD), Field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM) and Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) were used to characterize the produced CuO:B NCs. Test samples were analyzed by applying Cu-Kα radiation (λ = 1.54185 Å) in XRD (Thermo Scientific ARL X'TRA). FESEM was used for surface morphological properties and FTIR was used to determine chemical bonds. FTIR spectra were obtained in the range of 400-4000 cm-1.

Antimicrobial assay of CuO:B NCs

The antimicrobial activity of the synthesized CuO:B NCs against the tested bacteria was evaluated by agar well diffusion method. Gram positive (Enterococcus faecalis ATCC 29212, Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 25923) and gram negative (Salmonella enteridis ATCC 13075, Enterobacter aerogenes ATCC 13048 and Escherichia coli ATCC 25922) reference pathogen strains were used in the study. Pathogenic bacteria were cultured in Mueller-Hinton liquid medium (MHB) at 37 °C. Then, bacterial cultures (0.5 McFarland) were spread evenly on Mueller-Hinton Agar (MHA) media with cotton swabs. Wells were formed on the agar using sterile tips and 100 µL test samples were added to the wells. All plates were incubated at 37 °C for 24 hours and then inhibition zones were measured. Gentamicin was used as a positive control. Analyses were performed in 3 replicates.

Determination of minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC)

The MIC value of the synthesized CuO:B NCs was determined using the liquid microdilution method of the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) with some modifications. Bacterial cultures were diluted to 106 CFU/mL after 24 hours of incubation and 100 µL of bacterial culture was added to each well. Test samples were incubated for 18 hours at 37 °C by adding 100 µL of different concentrations (25-0.13 mg/mL) to 96-well plate. After incubation, the presence of bacterial growth was observed.

Antioxidant assay of CuO:B NCs

DPPH (2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl hydrate) was used to evaluate the antioxidant activity of CuO:B NCs. Briefly, test samples (50 µL) at different concentrations (0.03-1 mg/mL) were mixed with 0.1 mM DPPH (Sigma) methanol solution (150 µL) and kept in the dark for 30 min. Methanol and DPPH solutions were used as controls and a series of ascorbic acid solutions (0.03-1 mg/mL) were used as standards. The absorbance of the samples was then read at 517 nm using a spectrophotometer. The free radical scavenging activity of the test samples was calculated according to the following formula:

% DPPH radical inhibition = ((absorbance of control - absorbance of sample)/(absorbance of control)) × 100.

Cytotoxicity assay of CuO:B NCs

The A549 cell line was grown in DMEM high glucose containing 10% FBS (Pan Biotech P30-1301) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin in 25T flasks to 70% confluence and above. Samples were exposed to UV for 30 min and the initial concentration was adjusted to 500 µg/ml. 500 µL of trypsin-EDTA (Gibco, 15400054) was added to the cells and kept at 37 °C in 5% CO2 for 3-5 min. When the cells were observed to dissociate under an inverted microscope (Zeiss Primovert, Germany), medium containing 10% FBS was added. Centrifuge at 300×g for 5 minutes and discard the medium. Add 1 mL DMEM high glucose medium. Trypan blue (Gibco, 1525061) was used for counting on a Logos Luna II instrument. Medium containing 10% FBS was added to give 104 cells per well. Each group was made up of at least 3 replicate wells for repeated analyses. After application of the material, the cells were left in the incubator for 22 hours. Then, in a dark environment, 10% of the well volume of WST-8 solution was added. The cell culture dish was wrapped in aluminium foil and kept in the incubator for a further 2 hours. At the end of two hours, the cell culture dish was read at a wavelength of 450 nm. The results were formulated and the % viability was determined.

Apoptosis assay of CuO:B NCs

The Guava® Muse Cell Analyser was used with the Muse® Annexin V & Dead Cell Kit to detect live, dead and apoptotic cells in the test samples. Cells (5×104 cells/flask) were exposed to the sample concentration at the IC50 value determined in the cytoxicity assay for 24 hours. Analysis was performed according to the kit procedure. The suspended samples were analyzed in the instrument and the percentages of viable cells, early apoptotic cells and late apoptotic cells were determined by software.

Statistical analysis

All experiments were repeated three times and statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 8. Values are expressed as mean ± SD (standard deviation). Significance levels were accepted as p < 0.05. Student's t-test was used for statistical analysis of the results obtained.

XRD Analysis of CuO:B NCs

X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis was conducted to examine the crystallinity and phase purity of the synthesized CuO:B NCs (Fig. 1). The XRD pattern exhibited well-defined diffraction peaks at 2θ values of 35.44°, 36.51°, 38.58°, 42.39°, 49.08°, 61.39° and 73.79° which are characteristic of the monoclinic crystal structure of CuO:B nanoparticles [20]. These peaks correspond to the (002), (-111), (111), (200), (-202), (-113), (-311) and (221) planes, respectively (JCPDS number 01-080-0076). These sharp, well-defined peaks confirmed the crystalline nature of the nanoparticles and their monoclinic phase structure. Additionally, it was observed that boron addition did not change the monoclinic CuO structure but only caused a decrease in the peak intensity [17]. These XRD results strongly support the successful synthesis of pure CuO:B nanoparticles via the green method utilizing A. melanocarpa extract.

SEM Analysis of CuO:B NCs

The morphology and particle size of the synthesized CuO nanoparticles were thoroughly examined using Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM). FESEM images of CuO:B NCs are shown in Fig. 2. SEM images revealed that the CuO:B nanoparticles predominantly exhibited a spherical morphology, with some particles displaying occasional elongated or irregular shapes. The average particle size was estimated to range between 15 and 67 nm, based on three independent synthesis batches prepared under identical experimental conditions, confirming the reproducibility of the method. Notably, the nanoparticles were well-dispersed without significant agglomeration, which underscores the effective stabilization of the particles by the A. melanocarpa extract. The uniform distribution and relatively small particle size are pivotal for enhancing both surface area and reactivity, which are critical for a wide array of applications and antimicrobial treatments [21]. Moreover, the smooth surfaces and rounded shapes of the nanoparticles suggest a successful synthesis with minimal aggregation, which is vital for biomedical applications [22].

FTIR Analysis of CuO:B NCs

Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) was employed to identify the functional groups present in the synthesized CuO:B NCs and to investigate the interactions between the A. melanocarpa extract and the nanoparticles. The FTIR spectrum of the CuO:B NCs revealed distinct peaks at several wavenumbers (Fig. 3).

A broad band around 3664.8 cm-1 was attributed to the O-H stretching vibration of phenolic groups from the A. melanocarpa extract, which plays a key role in reducing copper ions to form CuO:B NCs [23]. The peaks at 693.7 cm-1 and 1032.1 cm-1 corresponded to C-H and C-O bending vibrations, respectively, confirming the presence of phenolic compounds and flavonoids in the extract, both of which contribute to the stabilization of the nanoparticles [24]. Moreover, the peak at 478.1 cm⁻¹ was associated with metal-oxygen stretching vibrations, confirming the successful formation of Cu-O-B nanoparticles [25]. Additional, a comparative analysis of the FTIR spectra of the A. melanocarpa extract and the synthesized CuO:B nanoparticles clearly demonstrates that the functional groups from the plant extract are actively involved in the synthesis process, particularly in the reduction and stabilization of the nanoparticles. This strongly affirms the successful application of a green synthesis pathway in this study.

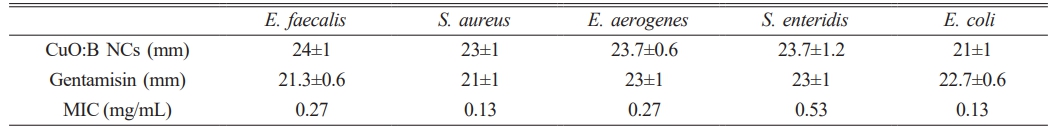

Antimicrobial activity of CuO:B NCs

The antimicrobial activities of CuO:B NCs synthesized from A. melanocarpa fruit extract against pathogenic bacteria. The negative control was not observed to form any zones. Inhibition zone diameters were 21-24 mm for CuO:B NC and 21-23 mm for the positive control. MIC values were determined in the range of 0.13-0.53 mg/mL (Table 1). According to the results, CuO:B NC showed strong microbicidal activity against all bacteria (Fig. 4). The highest antibacterial activity was observed for E. faecalis and the lowest for E. coli pathogens. Compared to the positive control, CuO:B NCs showed higher activity. Most nanocomposites are now known to be lethal to microorganisms. The antimicrobial activity of nanocomposites depends on several factors. Initially, the contact of nanocomposites with the cell and their incorporation into the cell is the first step. Nanocomposites can enter the cell by various transfer mechanisms such as endocytosis and phagocytosis [26]. Once inside the cell, nanocomposites can induce oxidative stress through the release of reactive oxygen species (ROS) [27]. Oxidative stress can be eliminated by the cell at normal levels. However, excessive oxidative stress can cause DNA damage, disruption of cell membrane structure, protein denaturation, lipid peroxidation and mitochondrial damage. Thus, apoptosis or necrosis processes can be induced in the cell [28]. Copper ions can cause oxidative stress to the cell membrane, leading to the release of cell contents and cell death [29]. Boron compounds can have antimicrobial effects by disrupting cell metabolism and the structure and function of proteins and lipids in the cell membrane [30]. In this study, the strong antimicrobial activity of CuO:B nanocomposites was attributed to the synergistic effect of CuO and boron compounds.

The antimicrobial properties of nanocomposites have been extensively investigated, demonstrating broad-spectrum activity against various pathogenic microorganisms. For instance, gum arabic-based CuO-ZnO nanocomposites produced inhibition zones ranging from 21 to 25 mm against E. coli, S. typhimurium, S. aureus, S. epidermidis, and B. subtilis [31]. Similarly, CuO-NiO nanocomposites exhibited notable antibacterial activity against S. aureus (18 mm), S. pyogenes (20 mm), K. pneumoniae (16 mm), and E. coli (18 mm) at a concentration of 30 µg/mL [32]. In another study utilizing green synthesis, boron-containing CuO nanocomposites formed inhibition zones of approximately 15 mm against both S. aureus and E. coli [16]. Furthermore, Zn/CuO and Ni/CuO nanocomposites demonstrated inhibition zones of 18 mm and 19 mm, respectively, against S. aureus, and 16 mm and 17 mm against E. coli strains [33]. These antimicrobial effects are believed to result from the nanoscale particle sizes (40-60 nm) and the metal oxide components of the composites. In the present study, boron-doped CuO nanocomposites exhibited enhanced antibacterial activity, producing inhibition zones of 23 mm and 21 mm against S. aureus and E. coli, respectively. Consistent with previous reports, nanocomposite systems often exhibit synergistic antimicrobial effects compared to their single-metal counterparts, likely due to the combination of metal oxides and surface functionalization strategies [34]. Therefore, the enhanced antimicrobial performance of the boron-doped CuO nanocomposites in this study may be attributed to their uniform distribution and relatively small particle sizes (15-67 nm).

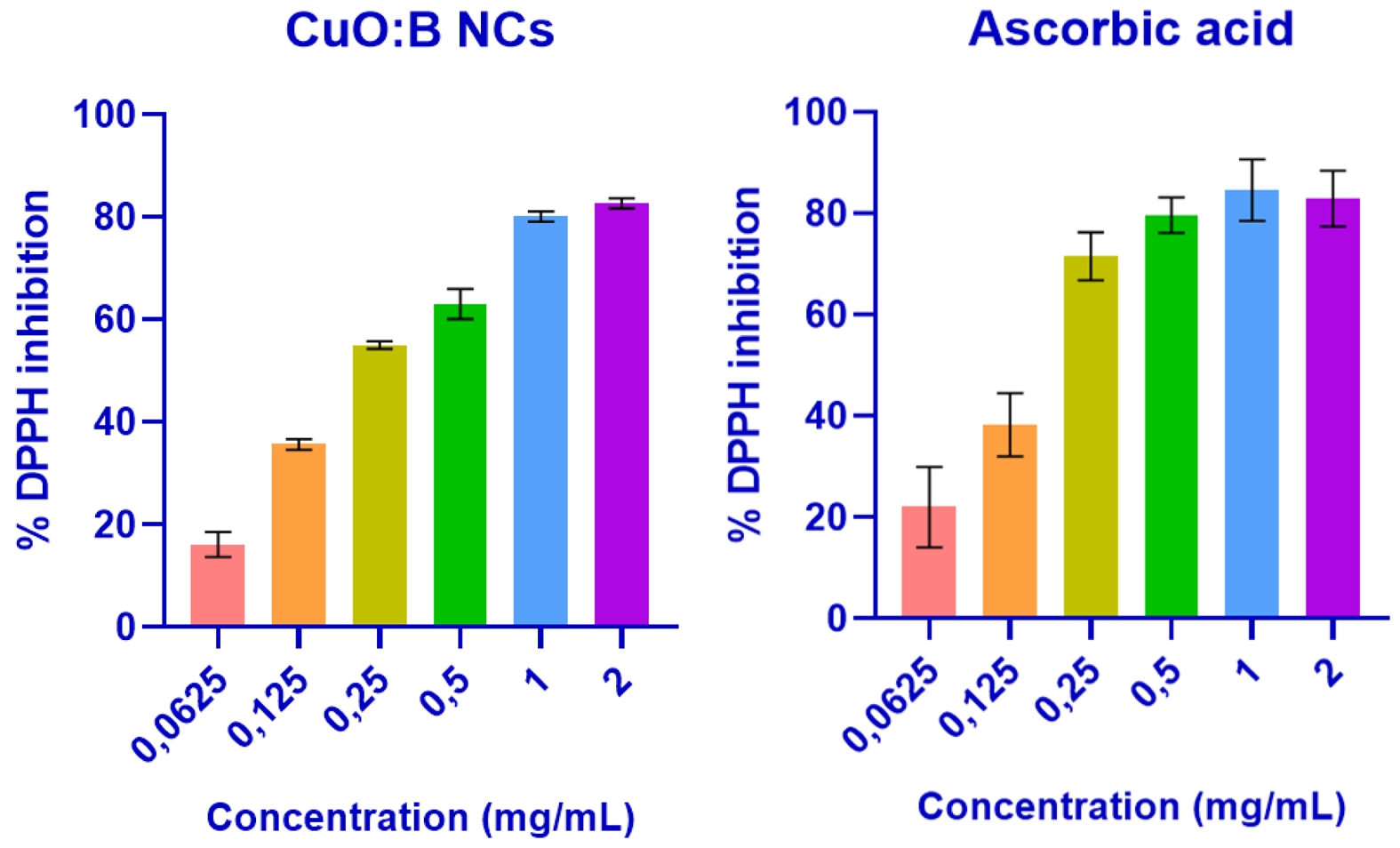

Antioxidant activity of CuO:B NCs

The DPPH test was performed to evaluate the antioxidant activity of the biosynthesized CuO:B NCs. As a result of the analysis, it was observed that the test samples exhibited strong antioxidant properties. As a result of the calculations, the IC50 value of CuO:B NCs was determined to be 0.21 mg/mL. When the samples were compared with ascorbic acid (IC50=0.14 mg/mL), they were found to have a close antioxidant effect (Fig. 5).

The antioxidant properties of green-synthesized CuO NCs are derived from both metal oxides and plants. When nanocomposites enter the cell, Cu ions biochemically react with free radical species in the environment and reduce them. The large surface area of nanocomposites allows them to interact with more free radicals [35]. These nanomaterials can degrade hydrogen peroxide by acting as a catalase enzyme. In addition, the antioxidant properties increase depending on the properties of the plant used in the synthesis. In particular, biomolecules such as flavonoids, polyphenols and saponins found in plants have strong antioxidant properties. These antioxidants reduce ROS in cells and reduce oxidative stress. This antioxidant property of both metal oxides and plant biomolecules shows a synergistic effect, allowing nanocomposites to show stronger antioxidant activity [36]. In the present study, the fruits of the plant A. melanocarpa were used as a reducing agent. This plant is known for its rich phytocomponents and strong antioxidant properties [37]. In the literature, there are only one or two studies on nanoparticles produced by A. melanocarpa plant [18, 19, 38]. When the antioxidant activity of silver nanoparticles synthesized using A. melanocarpa fruit extract was investigated, it was reported to have a promising antioxidant effect [19]. When compared with previous studies, the IC₅₀ value of biosynthesized CuO-NiO nanocomposites was reported to be 0.184 mg/mL, which is comparable to that of ascorbic acid (IC₅₀: 0.16 mg/mL) [32]. Similarly, CuO-ZnO nanoparticles synthesized using Eryngium foetidum extracts exhibited an IC₅₀ value of 0.253 mg/mL, an activity likely attributed to the presence of phenolic and flavonoid compounds in the plant extract [39]. In another report, Cu/NiO nanocomposites synthesized via a green route using Commelina benghalensis leaf extract demonstrated a DPPH radical scavenging activity of 54.44% at a concentration of 0.2 mg/mL [40]. In the present study, CuO:B nanocomposites exhibited a radical scavenging activity of 55% at 0.25 mg/mL, indicating antioxidant performance comparable to, and in some cases slightly higher than, similar green-synthesized systems reported in the literature. These results highlight that both the choice of plant source and the specific metal oxide composition substantially influence the biological activity of nanocomposites. The antioxidant potential observed in CuO:B nanocomposites may be attributed to the synergistic effect of boron doping on redox behavior, along with functional groups derived from phytochemical-mediated surface modifications during the biosynthesis process.

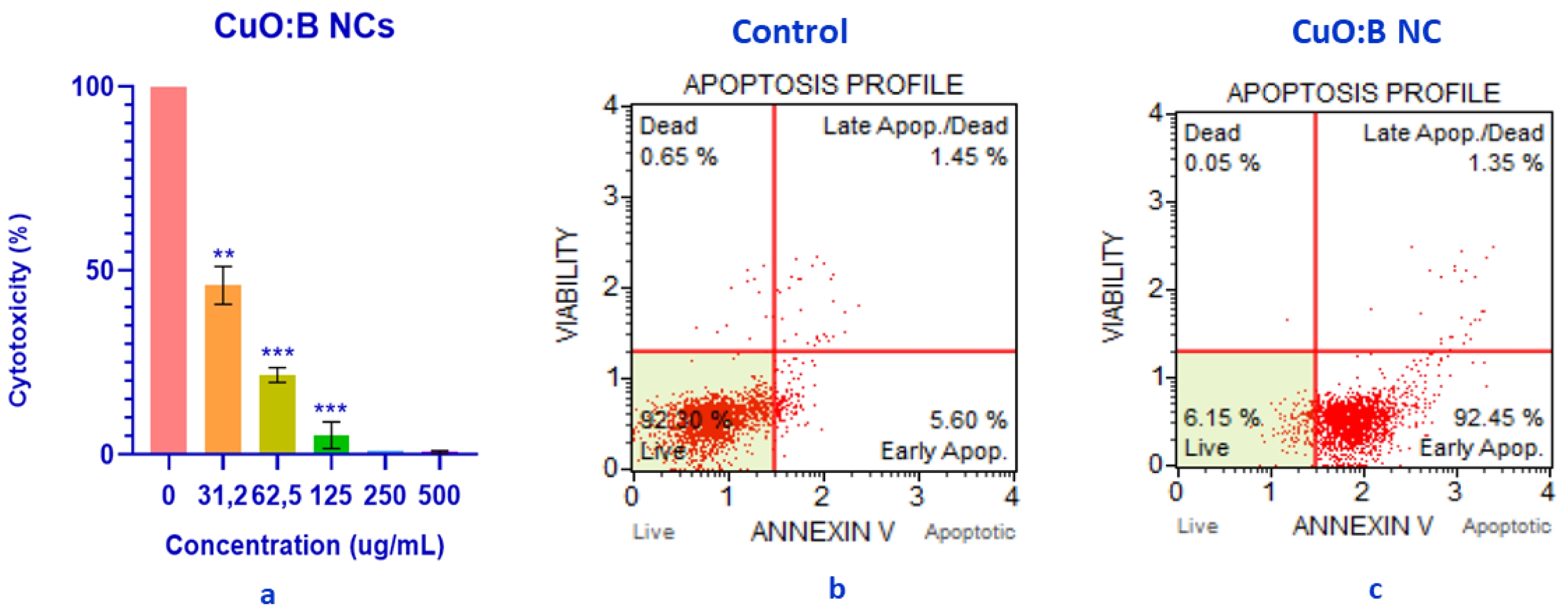

Anticancer activity of CuO:B NCs

The cytotoxicity of CuO:B NCs in A549 lung cancer cell lines was analyzed at a range of different concentrations (31.2-500 µg/mL) for a period of 24 hours. The results showed that most of the CuO:B NCs killed most of the cancer cells and had significant anticancer activity with a calculated IC50 value of 30.57 µg/mL (Fig. 6a). The viability of A549 cancer cells following exposure to CuO:B nanocomposites was determined to be 5.2% at a concentration of 125 µg/mL, 21.6% at 62.5 µg/mL, and 45.93% at 31.2 µg/mL. These results demonstrated a statistically significant, dose-dependent decrease in cell viability (p < 0.01 and p < 0.001), indicating a pronounced cytotoxic effect of CuO:B nanocomposites on A549 cells.

In addition to the cytotoxicity analysis, the apoptotic profile of A549 cancer cells was examined at the IC50 value of CuO:B NCs for 24 hours. As a result of the analysis, it was observed that CuO:B NCs induced apoptosis in A549 cells. Surviving cells were 92.30% in the control group and 6.15% in the CuO:B NC-treated group (Fig. 6b). The total number of apoptotic cells was 98.30% in the CuO:B NC-containing group and the cells were found to undergo early apoptosis (Fig. 6c).

Nanocomposites accumulate by entering the cytoplasm directly through the cell membrane or by ion transport. This accumulation leads the cell to apoptosis by increasing ROS and thus oxidative stress [41]. The anticancer mechanism of CuO NPs involves processes leading to cell death such as oxidation of lipids to the cell membrane, oxidative stress, denaturation of DNA and proteins, chromosomal abnormalities and caspase production [1]. The production of caspases initiates apoptosis, or programmed cell death. Apoptosis is a death mechanism that eliminates unwanted, harmful cells without harming healthy cells. As a result, it is an important method for the elimination of cancer cells [42]. The CuO:B NCs produced in this study are thought to have similar effects in the cytoplasm, driving the cell into early apoptosis and causing the death of cancer cells.

CuO:B nanocomposites synthesized via a green approach exhibited cytotoxic behavior comparable to several previously reported biosynthesized metal oxide nanoparticles. For instance, CuO nanoparticles produced using Abutilon indicum leaf extract demonstrated potent anticancer activity against A549 lung carcinoma cells, with an IC₅₀ value of 16 μg/mL, which was attributed to the presence of bioactive molecules and nanoparticle concentration [43]. Likewise, silver-doped CuO nanoparticles synthesized using Moringa oleifera leaf extract exhibited an IC₅₀ value of 25 μg/mL in A549 cells [44].

In another study, CuO nanoparticles derived from walnut shells induced cytotoxicity and apoptosis in breast and colon cancer cell lines, suggesting involvement in both direct cytotoxic and programmed cell death pathways [41]. Furthermore, CuO-ZnO nanoparticles synthesized through green methods displayed notable toxicity against MCF-7 cells, with a maximum inhibition rate of 89.2% at 500 μg/mL and an IC₅₀ value of 239.99 μg/mL [39]. However, CuO-ZnO nanocomposites synthesized using gum arabic demonstrated more pronounced anticancer effects, with IC₅₀ values of 54.7 μg/mL and 79.2 μg/mL against MCF-7 and HepG2 cells, respectively [31].

A comparison of the findings from the present study with previous reports suggests that the anticancer activity of boron-doped CuO nanoparticles may differ significantly depending on cell type and nanoparticle concentration. In a prior study, biosynthesized CuO:B nanoparticles exhibited potent cytotoxicity in HepG2 cells, with an IC₅₀ value of 4.98 µg/mL and an early apoptosis rate of 25.65%, which was attributed to caspase-7 activation as revealed by in silico analyses [17]. In contrast, the current study determined an IC₅₀ value of 30.57 µg/mL in A549 cells, accompanied by a markedly higher early apoptosis rate of 92.45%. These discrepancies may arise from cell-specific sensitivities, variations in nanoparticle size and surface characteristics, and differences in the phytochemical content of the plant extract used during biosynthesis. Overall, boron-doped CuO nanoparticles have been reported to exert anticancer effects primarily by inducing apoptosis, though the extent and mechanism of action appear to be dose- and cell line-dependent.

Conclusion

The successful green synthesis of CuO:B nanocomposites using A. melanocarpa extract underscores the potential of plant-mediated methods as sustainable alternatives to conventional approaches. XRD analysis confirmed the formation of a stable monoclinic CuO phase, while SEM and FTIR results supported the presence of uniformly distributed nanoparticles and Cu-O bonding. The phytochemicals in A. melanocarpa played a crucial role in controlling nanoparticle morphology. Biologically, the CuO:B nanocomposites exhibited remarkable multifunctional activity. They showed strong antimicrobial efficacy, with Staphylococcus aureus displaying the highest susceptibility (23 mm inhibition zone), indicating potential use against drug-resistant bacterial strains. The antioxidant activity was comparable to that of ascorbic acid, highlighting their ability to neutralize free radicals and reduce oxidative stress. In anticancer assays, the nanocomposites exerted significant cytotoxic effects against the A549 lung cancer cell line, inducing early apoptosis in a majority of the cells. These results suggest that the synergistic interaction between copper, boron, and the rich phytochemical matrix of A. melanocarpa enhances their bioactivity. Therefore, the synthesized nanocomposites hold great promise as potential therapeutic agents in the treatment of infectious diseases, oxidative stress-related disorders, and cancer. Further in vivo and in vitro studies are warranted to fully explore their biomedical applications.

|

Fig. 1 XRD patterns of biosynthesized CuO:B NCs from A. melanocarpa fruit extract. |

|

Fig. 2 FESEM images of biosynthesized CuO:B NCs from A. melanocarpa fruit extract. |

|

Fig. 3 FTIR spectrum of biosynthesized CuO:B NCs from A. melanocarpa fruit extract. |

|

Fig. 4 Antimicrobial activity of biosynthesized CuO:B NCs from A. melanocarpa fruit extract. 1: E. aerogenes, 2: E. faecalis, 3: S. enteridis, 4: S. aureus, 5: E. coli. NC: Negative control, PC: Positive control. |

|

Fig. 5 Antioxidant activity of biosynthesized CuO:B NCs from A. melanocarpa fruit extract. |

|

Fig. 6 Anticancer activity of biosynthesized CuO:B NCs on A549 cancer cells. a) Cytotoxic effect, b) Apoptotic profile of A549 cancer cells, c) Apoptotic profile of CuO:B-treated A549 cancer cells. |

|

Table 1 Antibacterial activity and MIC results of biosynthesized CuO:B NCs against the tested pathogenic strains. |

CuO:B NCs; Boron doped CuO nanocomposites, MIC; Minimum inhibitor concretions of pathogen bacteria |

The authors gratefully acknowledge the ÜSKİM Research Center, Kahramanmaraş Sütcü Imam University.

The authors declare no competing interests.

This work was supported by a grant from the Kahramanmaraş Sütçü İmam University Scientific Research Projects Unit, Project Number: 125/5-25 M.

- 1. B. Murugan, M.Z. Rahman, I. Fatimah, J.A. Lett, J. Annaraj, N.H.M. Kaus, M.A. Al-Anber, and S. Sagadevan, Inorg. Chem. Commun. 155 (2023) 111088.

-

- 2. S. Chen, A. Fan, Y. Zhong, and J. Tang, Arab. J. Chem. 15[3] (2022) 103561.

-

- 3. E.J. Ge, A.I. Bush, A. Casini, P.A. Cobine, J.R. Cross, G.M. DeNicola, Q.P. Dou, K.J. Franz, V.M. Gohil, S. Gupta, and S.G. Kaler, Nat. Rev. Cancer 22[2] (2022) 102-113.

-

- 4. N. Chakraborty, J. Banerjee, P. Chakraborty, A. Banerjee, S. Chanda, K. Ray, K. Acharya, and J. Sarkar, Green Chem. Lett. Rev. 15[1] (2022) 187-215.

-

- 5. Z. Alhalili, Arab. J. Chem. 15[5] (2022) 103739.

-

- 6. K. Ramasubbu, S. Padmanabhan, K.A. Al-Ghanim, M. Nicoletti, M. Govindarajan, N. Sachivkina, and V.D. Rajeswari, Fermentation 9[4] (2023) 332.

-

- 7. B. Kirlangiç and E. Çakmak, ChemistrySelect. 9 (2024) e202402226.

-

- 8. A. Biţă, I.R. Scorei, T.A. Bălşeanu, M.V. Ciocîlteu, C. Bejenaru, A. Radu, L.E. Bejenaru, G. Rau, G.D. Mogosanu, J. Neamtu, and S.A. Benner, Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23 (2022) 9147.

-

- 9. F.Ç. Çelikezen and İ.H. Şahin, Bitlis Fen 12[3] (2023) 591-595.

-

- 10. H. Turkez, M.E. Arslan, A. Tatar, and A. Mardinoglu, Neurochem. Int. 149 (2021) 105137.

-

- 11. A.A.J. Jabbar, Z.Z. Alamri, M.A. Abdulla, N.A. Salehen, I.A.A. Ibrahim, R.R. Hassan, G. Almaimani, G.A. Bamagous, R.A. Almaimani, H.A. Almasmoum, M.M. Ghaith, W.F. Farrash, and Y.A. Almutawif, Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 202[6] (2024) 2702-2719.

-

- 12. E. Çakmak, E. Kiray, A. Tanrıverdi, and S. Tekerek, MRS Commun. 14[1] (2024) 121-128.

-

- 13. A.H. Hashem, S.H. Rizk, M.A. Abdel-Maksoud, W.H. Al-Qahtani, H. AbdElgawad, and G. S. El-Sayyad, RSC Adv. 13[30] (2023) 20856-20867.

-

- 14. N. Kadiyala, T.S. Rao, D. Gorli, S.S. Supriya, S. Vidavalur, and Raffiunnisa, Inorg. Chem. Commun. 162 (2024) 112240.

-

- 15. S. Tekerek, A. Tanrıverdi, E. Kiray, and E. Çakmak, Braz. J. Phys. 54 (2024) 35.

-

- 16. E. Veg, A. Raza, S. Rai, S. Sharma, A. Pandey, M. I. Ahmad, S. Jabeen, S. Joshi, and T. Khan Chem. Biodiversity 22 (2025) e202401596.

-

- 17. M. Cengiz, O. Baytar, Ö. Şahin, H.M. Kutlu, A. Ayhanci, C. Vejselova Sezer, and B. Gür, J. Clust. Sci. 35[1] (2024) 265-284.

-

- 18. J. Huang, J. Sun, K. Shao, Y. Lin, Z. Liu, Y. Fu, and L. Mu, J. Renew. Mater. 11[4] (2022) 1807-1821.

-

- 19. A. Corciovă, C. Mircea, A. Fifere, I.A. Turin-Moleavin, I. Roşca, I. Macovei, B. Ivanescu, A.M. Vlase, M. Hancianu, and A. F. Burlec, Life 14[9] (2024) 1211.

-

- 20. A.A. Badawy, N.A.H. Abdelfattah, S.S. Salem, M.F. Awad, and A. Fouda, Biology 10[3] (2021) 233.

-

- 21. A. Menichetti, A. Mavridi-Printezi, D. Mordini, and M. Montalti, J. Funct. Biomater. 14 (2023) 244.

-

- 22. A. Singh, S.L. Banerjee, A. Gantait, K. Kumari, P.P. Kundu, in “Nanoparticles Reinforced Metal Nanocomposites: Mechanical Performance and Durability” (Springer Nature, Singapore 2023) p. 365-408.

-

- 23. B. Djamila, L.S. Eddine, B. Abderrhmane, N. Nassiba, and A. Barhoum, Biomass Conv. Bioref. 14 (2024) 6567-6580.

-

- 24. F. Khoerunnisa, M. Nurhayati, H. Herlini, Q.A.A. Adzkia, F. Dara, H. Hendrawan, W.D. Oh, and J. Lim J. Water Process Eng. 52 (2023) 103556.

-

- 25. S. Jabeen, V.U. Siddiqui, S. Rastogi, S. Srivastava, S. Bala, N. Ahmad, and T. Khan, Mater. Today Chem. 33 (2023) 101712.

-

- 26. L. Wang, C. Hu, and L. Shao, Int. J. Nanomedicine. 12, (2017) 1227-1249.

-

- 27. N.A. Rosli, Y.H. Teow, E. Mahmoudi, Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 22[1] (2021) 885-907.

-

- 28. S.V. Gudkov, D.E. Burmistrov, P.A. Fomina, S.Z. Validov, and V.A. Kozlov, Int. J. Mol. Sci. 25[21] (2024) 11563.

-

- 29. X. Fan, L.H. Yahia, and E. Sacher, Biology 10[2] (2021) 137.

-

- 30. O. Celebi, D. Celebi, S. Baser, E. Aydın, E. Rakıcı, S. Uğraş, P. Agyar Yoldas, N.K. Baygutalp, and A.M. Abd El-Aty, Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 202[1] (2024) 346-359.

-

- 31. G.S. El-Sayyad, E.S.R. El-Sayed, S.H. Rizk, M.A. Abdel-Maksoud, A.M. Zakri, A. Malik, M.N. Malash, and A.H. Hashem, RSC Adv. 15[1] (2025) 513-523.

-

- 32. P. Prabu and V. Losetty, Inorg. Chem. Commun. 176 (2025) 114267.

-

- 33. P.V. Kumar, K. Raja, K. Nagaraj, N. Arumugam, A.J. Ahamed, M. Karthikeyan, and L.A. Devi, ChemistrySelect 10 (2025) e00004.

-

- 34. A.K. El-Sawaf, S.H. El-Moslamy, E.A. Kamoun, and K. Hossain, Sci. Rep. 14 (2024) 19718.

-

- 35. T.T.T. Nguyen, Y.N.N. Nguyen, X.T. Tran, T.T.T. Nguyen, and T.V. Tran, J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 11 (2023) 111003.

- 36. H.N. Cuong, S. Pansambal, S. Ghotekar, R. Oza, H.N. T. Thanh, N.M. Viet, and V.H. Nguyen, Environ. Res. 203 (2022) 111858.

-

- 37. J. Xu, F. Li, M. Zheng, L. Sheng, D. Shi, and K. Song, Plants 13[24] (2024) 3557.

-

- 38. P. Velmurugan, K.A. Vedhanayakisri, Y.J. Park, J.S. Jin, and B.T. Oh, Fibers Polym. 20 (2019) 302-311.

-

- 39. J. Daimari and A.K. Deka, Sci. Rep. 14 (2024) 19506.

-

- 40. R. Kumar, K. Kumar, N. Thakur, A. Umar, A.A. Ibrahim, S. Akbar, and S. Baskoutas, Chemosphere 362 (2024) 142805.

-

- 41. Y.J. Wong, H. Subramaniam, L.S. Wong, A.C.T.A. Dhanapal, Y.B. Chan, M. Aminuzzaman, L.H. Tey, A.K. Janakiraman, S. Kayarohanam, and S. Djearamane, Green Process. Synth. 13[1] (2024) 20240164.

-

- 42. H. Abdollahzadeh, Y. Pazhang, A. Zamani, and Y. Sharafi, Sci. Rep. 14 (2024) 20323.

-

- 43. S. Sathiyavimal, E.F. Durán-Lara, S. Vasantharaj, M. Saravanan, A. Sabour, M. Alshiekheid, N.T.L. Chi, K. Brindhadevi, and A. Pugazhendhi, Food Chem. Toxicol. 168 (2022) 113330.

-

- 44. D.R.A. Preethi, S. Prabhu, V. Ravikumar, and A. Philominal, Mater. Today Commun. 33(2022) 104462.

-

- 45. R. Gitmiş, and A. Tanrıverdi, J. Ceram. Process. Res. 26[4] (2025) 586-595.

-

This Article

This Article

-

2025; 26(6): 1024-1031

Published on Dec 31, 2025

- 10.36410/jcpr.2025.26.6.1024

- Received on Sep 16, 2025

- Revised on Nov 4, 2025

- Accepted on Nov 17, 2025

Services

Services

- Abstract

introduction

material and methods

results and discussion

- Acknowledgements

- Conflict of Interest

- Funding

- References

- Full Text PDF

Shared

Correspondence to

Correspondence to

- Esen Çakmak

-

Department of Bioengineering and Sciences, Graduate School of Natural and Applied Sciences, Kahramanmraş Sütcü Imam University, Kahramanmaras, Turkey

Tel : +90 344 300 27 74 Fax: +90 344 300 28 02 - E-mail: esencakmak@ksu.edu.tr

Copyright 2019 International Orgranization for Ceramic Processing. All rights reserved.

Copyright 2019 International Orgranization for Ceramic Processing. All rights reserved.