- The role of eggshell as a biomaterial in iron-titanium mixtures: innovation and sustainability

Aslı Betül Yönetkena,* and Ahmet Yönetkenb

aAnkara Yıldırım Beyazıt University,Faculty of Dentistry,Department of Prosthodontics, Yayla Mahallesi Yozgat Bulvarı, 1487. Cadde No:55 Keçiören / Ankara, Türkiye

bAfyon Kocatepe University, Technology Faculty, Mechatronics Engineering Dept., 03200, Afyonkarahisar, TürkiyeThis article is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

In this study, Fe-Ti-based composite materials reinforced with varying amounts of EggShell (3-13 wt.%) were fabricated and sintered at 750 °C under an argon atmosphere. Six different compositions were prepared by gradually decreasing Fe and Ti content while increasing the EggShell ratio. The purpose of the study was to investigate the influence of bioceramic (CaCO₃-based) EggShell addition on the microstructural evolution, densification behavior, and potential biofunctionality of the Fe-Ti matrix. The sintering process was carried out in an inert argon atmosphere to prevent oxidation and to ensure controlled diffusion between phases. Preliminary results suggest that the EggShell addition alters the phase composition and porosity, potentially improving the biocompatibility and tailoring the mechanical properties of the composites. These findings may contribute to the development of cost-effective, eco-friendly, and biocompatible materials for biomedical or structural applications.

Keywords: Ceramic-metal composite, Eggshell powder, Innovation, Powder metallurgy.

Metal matrix composites (MMCs) have gained increasing attention as advanced engineering materials due to their ability to combine the ductility and toughness of metallic matrices with the hardness, wear resistance, and thermal stability of ceramic reinforcements [1, 8]. Their high specific strength, corrosion resistance, and tunable mechanical properties make MMCs suitable for demanding applications in aerospace, automotive, energy, and biomedical industries [9-11].

Among various metal matrix systems, iron (Fe)-based composites are particularly attractive because of their low cost, abundance, magnetic properties, and reliable mechanical performance [12-14]. The addition of titanium (Ti) into Fe matrices further enhances corrosion resistance, reduces density, and improves biocompatibility, thus expanding their usability in biomedical and structural applications [15-17]. Fe–Ti alloys have been widely explored for dental prostheses, orthopedic implants, and lightweight components, yet ongoing research continues to seek improvements in microstructural stability, mechanical strength, and multifunctional performance through tailored reinforcement strategies [18-23].

In recent years, growing emphasis on sustainable materials engineering has promoted the use of bio-derived or waste-derived ceramic reinforcements in metal matrices. Eggshell, a biologically abundant waste material primarily composed of calcium carbonate (CaCO₃), offers a low-cost and environmentally friendly reinforcement alternative [24, 25]. Upon thermal decomposition to calcium oxide (CaO), eggshell-derived ceramic phases may enhance interfacial bonding, oxidation resistance, and biocompatibility within metallic matrices [26, 27]. This approach also supports waste valorization and aligns with global trends toward green composite development [28, 29].

Extensive studies have reported the significant influence of ceramic reinforcements on the densification, microstructure, hardness, and wear resistance of metal matrix systems [5-7, 13, 14]. In Fe–Ti-based composites, the introduction of ceramic phases such as TiB₂, ZrO₂, SiC, or CaO has been shown to enhance sintering behavior and improve overall mechanical performance [3, 4, 30-32]. Similarly, bioceramic-reinforced titanium-based systems exhibit improved structural integrity and biocompatibility due to the presence of calcium-containing phases [10, 22]. Hybrid composites integrating traditional ceramics with natural fillers such as eggshell powder have demonstrated increases in hardness, reductions in density, and improvements in microstructural uniformity, confirming the potential of natural waste-derived reinforcements in advanced composite design [24, 25].

Building upon these insights, the present study investigates Fe–Ti-based composites reinforced with varying amounts (3-13 wt.%) of eggshell powder, fabricated via powder metallurgy and sintered at 750 °C under an argon atmosphere. The objective is to evaluate the influence of eggshell addition on microstructure, densification, mechanical behavior, and potential biofunctionality of the Fe–Ti matrix. Given the formation of CaO from eggshell decomposition and the resulting multiphase composite structure, Fe–Ti–Eggshell systems may serve as promising candidates for lightweight components, corrosion-resistant coatings, thermal barrier applications, and biomedical devices such as dental implants and prosthetic frameworks, where both mechanical integrity and biocompatibility are essential [1-29].

This study contributes to the growing field of sustainable composite development by exploring an eco-friendly, low-cost reinforcement material integrated into a widely studied metal matrix system, providing insights into the engineering of next-generation composite materials with enhanced performance and environmental compatibility.

Materials

The materials utilized in this study included high-purity iron (Fe), titanium (Ti), and eggshell-derived calcium carbonate (EggShell). The Fe and Ti powders were obtained from certified suppliers with purities exceeding 99%. Eggshells were collected, thoroughly cleaned to remove organic residues, dried at 105 °C for 24 hours, and then ground into fine powder using a planetary ball mill.

Preparation of Powder Mixtures

Six different compositions were prepared with varying weight percentages of Fe, Ti, and EggShell, as summarized in Table 1.

Accurate weights of each component were measured using an analytical balance, and the powders were mixed uniformly in a planetary ball mill at 20 rpm for 2 hours.

Powder Metallurgy Processing

The homogeneous powder blends were cold-pressed into cylindrical green compacts with a diameter of 15 mm and height of 8-10 mm under a uniaxial pressure of 300 MPa. The green specimens were then sintered in a tube furnace at 750 °C for 2 hours under a continuous flow of high-purity argon gas to prevent oxidation. The sintering process was conducted at a controlled heating rate of 10 °C/min, and samples were cooled to room temperature within the furnace under argon atmosphere. Post-sintering, the samples were examined using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) to analyze the microstructure and phase distribution. X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis was performed to identify the phases present. Mechanical testing, including hardness measurements and compressive strength assessments, was carried out following standard protocols to evaluate the material properties.

|

Table 1 Effect of Eggshell Addition on the Fe–Ti Composition of the Prepared Samples. |

Physical Properties

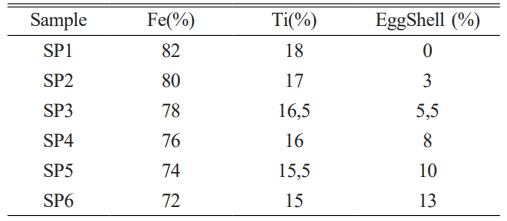

When the physical and mechanical properties of composite materials obtained from Fe-Ti-Eggshell powder mixtures sintered in an argon atmosphere at 750 °C were examined, significant changes were observed with increasing Eggshell content. Increasing Eggshell content resulted in a significant decrease in the density of the composites, which is attributed to Eggshell's lower density compared to metallic components. Similarly, porosity values initially decreased and then increased with increasing Eggshell content. This suggests that sintering efficiency increased at low additive content, while higher additive content weakened bonding and increased porosity. Microhardness values decreased steadily with increasing Eggshell content, which can be attributed to increased porosity and the lower mechanical strength of the ceramic phase. Consequently, while composites obtained with Eggshell reinforcement provide lightweight performance, careful optimization is required for mechanical strength and structural integrity.

Microstructural Investigation

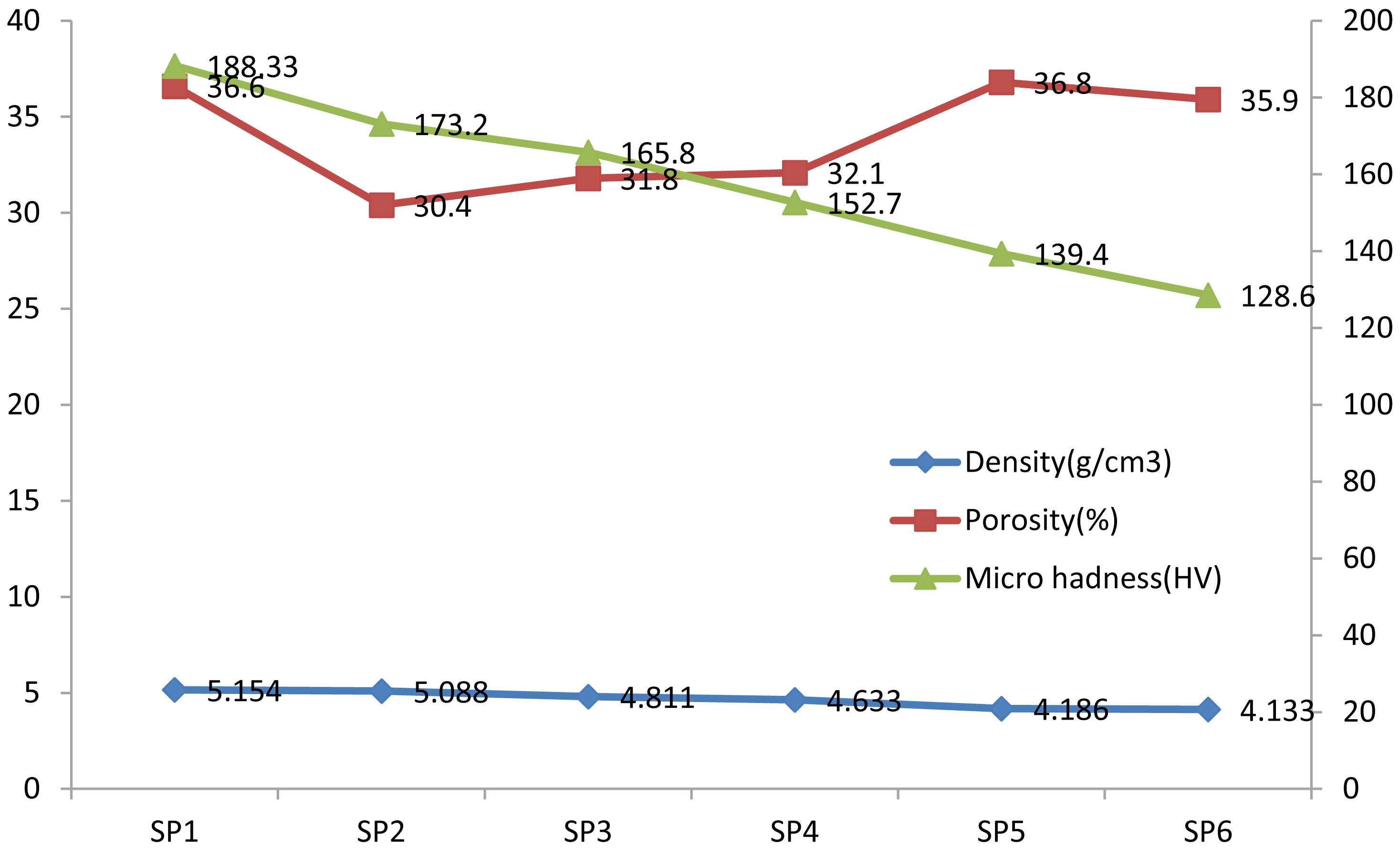

The SEM micrographs of Fe-Ti composites containing varying amounts of eggshell powder and sintered at 750 °C under an argon atmosphere reveal notable differences in microstructural characteristics (Fig. 2). In the sample without eggshell reinforcement (82Fe–18Ti), a relatively dense and compact microstructure with well-bonded particles is observed, indicating effective sintering and minimal porosity. As the eggshell content increases, beginning with the 3% addition (80Fe–17Ti–3%Eggshell), slight increases in pore formation and particle boundaries become evident. With further additions of 5.5% and 8% eggshell (Figures C and D), the microstructure displays more pronounced porosity and weakened interparticle bonding, suggesting that excessive bioceramic content interferes with densification. At higher reinforcement levels of 10% and 13% (Figures E and F), the micrographs reveal substantial pore presence and particle separation, with clear signs of agglomeration and incomplete sintering. These structural degradations correlate directly with the observed reductions in density and microhardness, indicating that high eggshell content adversely affects the mechanical integrity of the composites. Consequently, while eggshell offers benefits as a lightweight and eco-friendly additive, its proportion must be carefully optimized to preserve microstructural cohesion and ensure satisfactory performance.

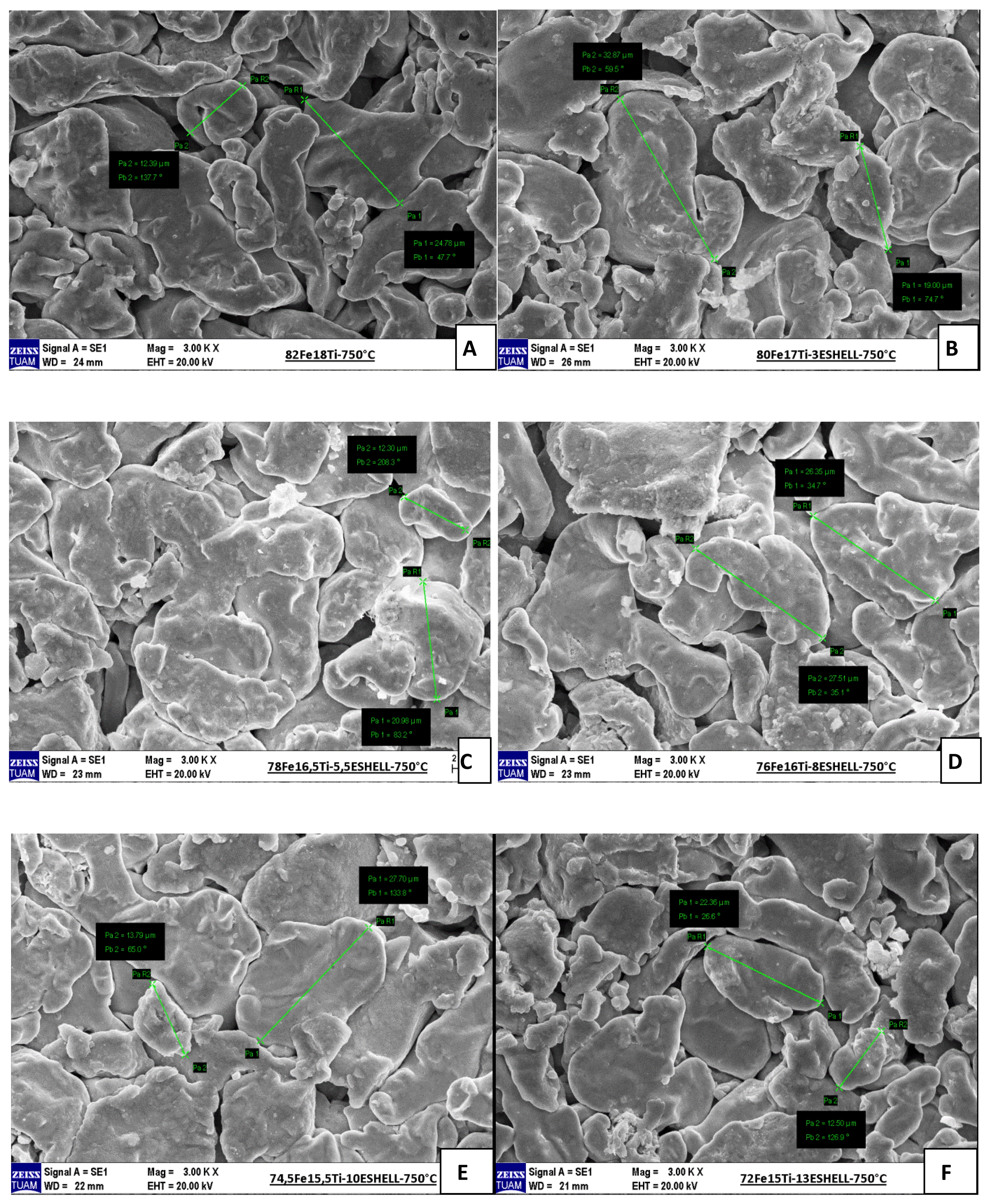

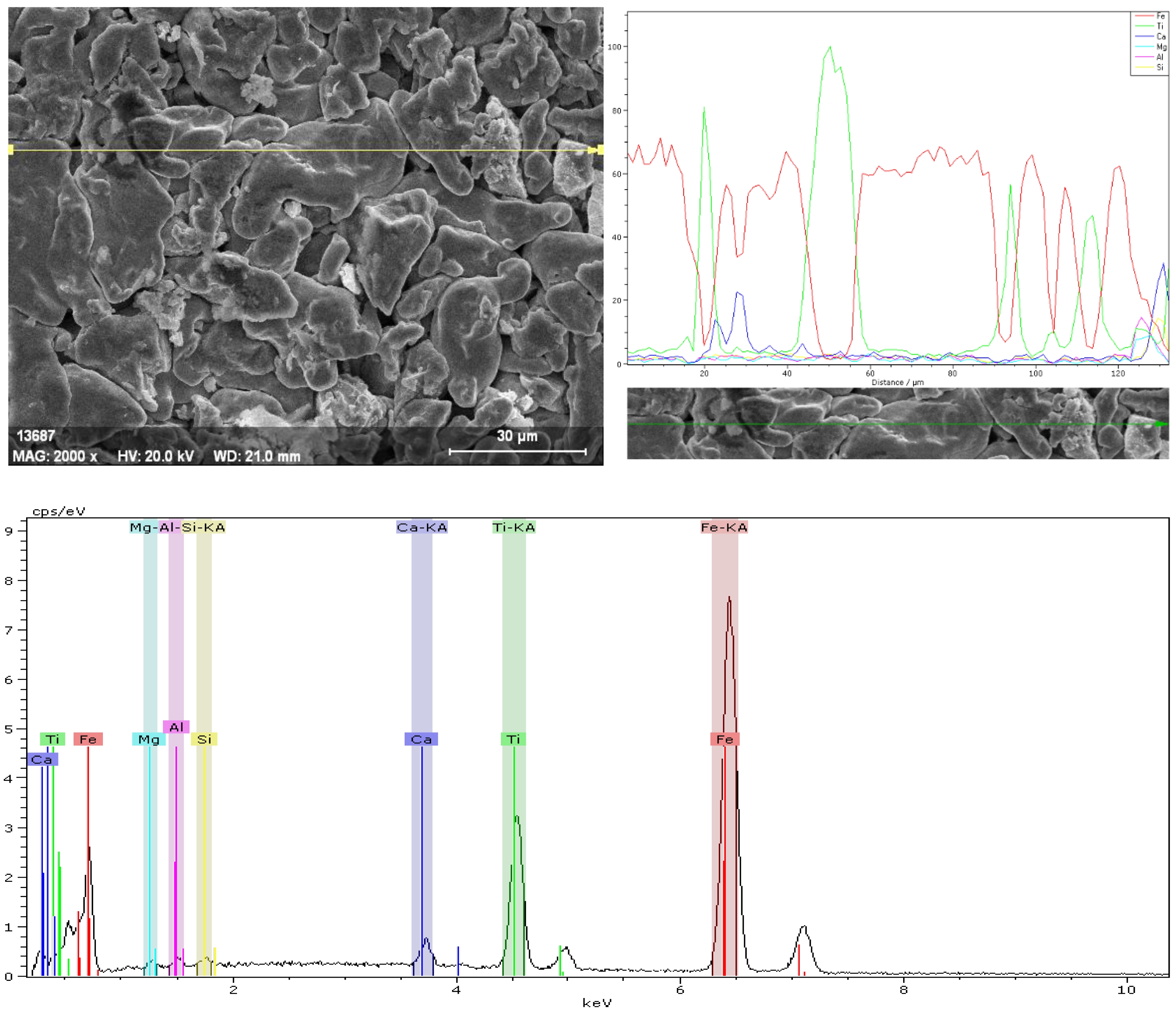

The EDX analysis of the SP1 sample sintered at 750 °C provides insights into both the elemental composition and distribution of the material (Fig. 3). The SEM micrograph at 2000× magnification reveals an irregular and porous microstructure with micron-sized particles. The line scan performed along the marked line demonstrates the spatial distribution of Fe and Ti elements. The Fe signal (red line) is relatively uniform across the scanned area, indicating that iron is the dominant and continuous phase in the microstructure. In contrast, the Ti signal (green line) shows localized peaks, suggesting that titanium is concentrated in specific regions rather than being homogeneously dispersed. The corresponding EDX spectrum confirms the presence of Fe and Ti as the major elements, with prominent Fe-Kα and Ti-Kα peaks. The relatively higher intensity of the Fe peaks compared to Ti indicates that Fe is the primary constituent, while Ti appears in lower quantities and is likely present as discrete particles or segregated phases. This localized enrichment of Ti may influence the mechanical and surface properties of the sintered composite, potentially contributing to variations in hardness or wear resistance across the surface.

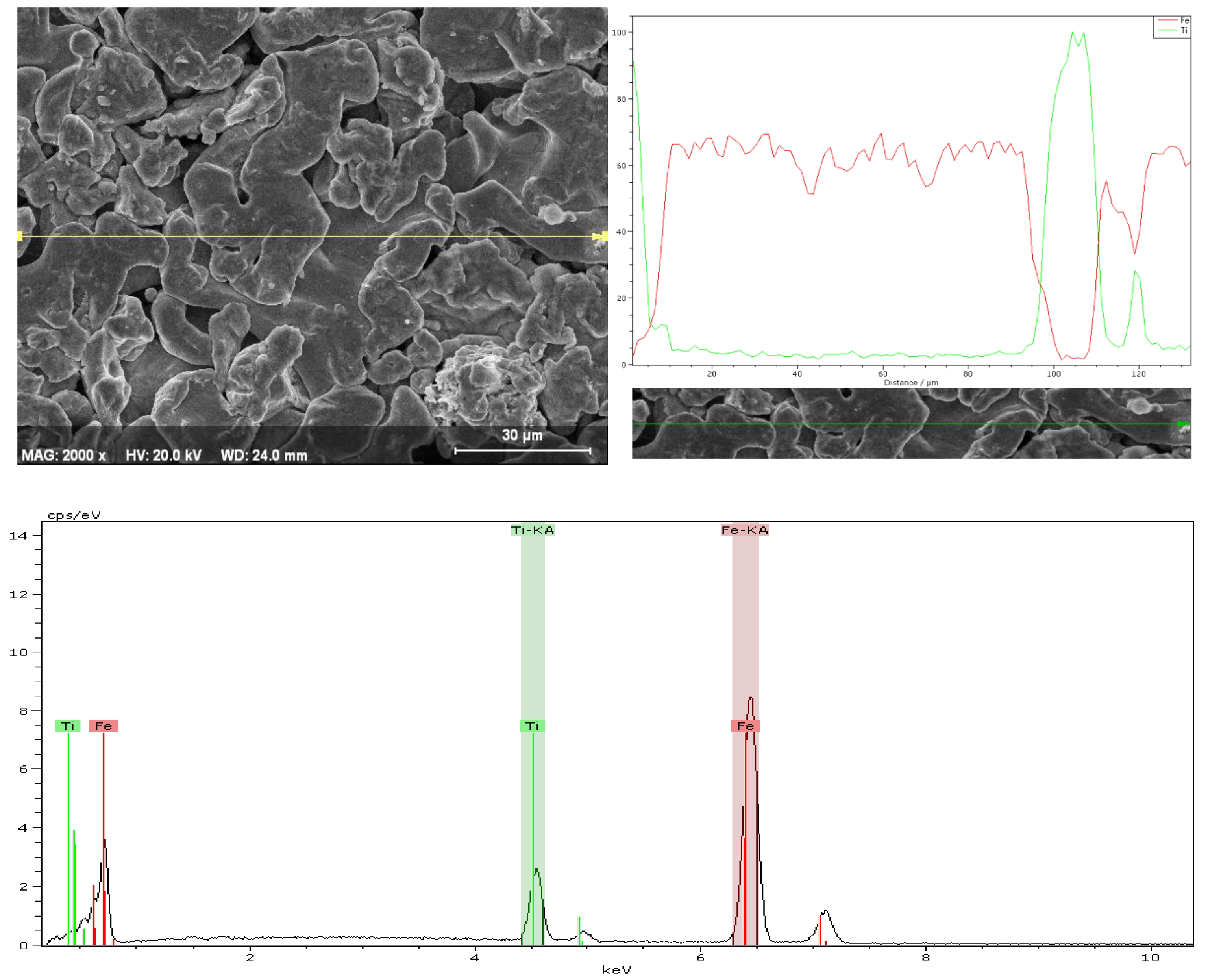

The EDX analysis of the SP6 sample sintered at 750 °C reveals detailed information regarding the elemental composition and distribution within the composite (Fig. 4). The SEM micrograph at 2000× magnification shows an irregular and porous microstructure with closely packed particles, consistent with sintered metallic composites. The line scan along the marked yellow line illustrates the spatial distribution of Fe, Ti, Ca, Mg, Al, and Si across the sample surface. Fe (red line) exhibits a relatively uniform distribution, indicating its role as the primary matrix element. Ti (green line) shows localized intensity peaks, suggesting its presence as discrete particles or segregated regions rather than being homogeneously dispersed. Minor elements such as Ca (blue line), Mg, Al, and Si appear in smaller quantities, with their signals presenting intermittent peaks along the scanned path, which indicates their localization at specific sites, likely corresponding to secondary phases or inclusions.

The EDX spectrum supports these observations by displaying distinct characteristic peaks of Fe-Kα and Ti-Kα, confirming Fe as the dominant phase and Ti as a secondary phase. The spectrum also shows smaller peaks corresponding to Ca, Mg, Al, and Si, which are typically associated with either surface oxides or reinforcing particles within the composite. The relatively higher intensity of Fe peaks highlights the metallic matrix, while the heterogeneity of the Ti and minor elements reflects the composite nature of the material. This localized elemental enrichment could influence the overall mechanical behavior, potentially enhancing hardness or wear resistance in regions with Ti and ceramic-related phases.

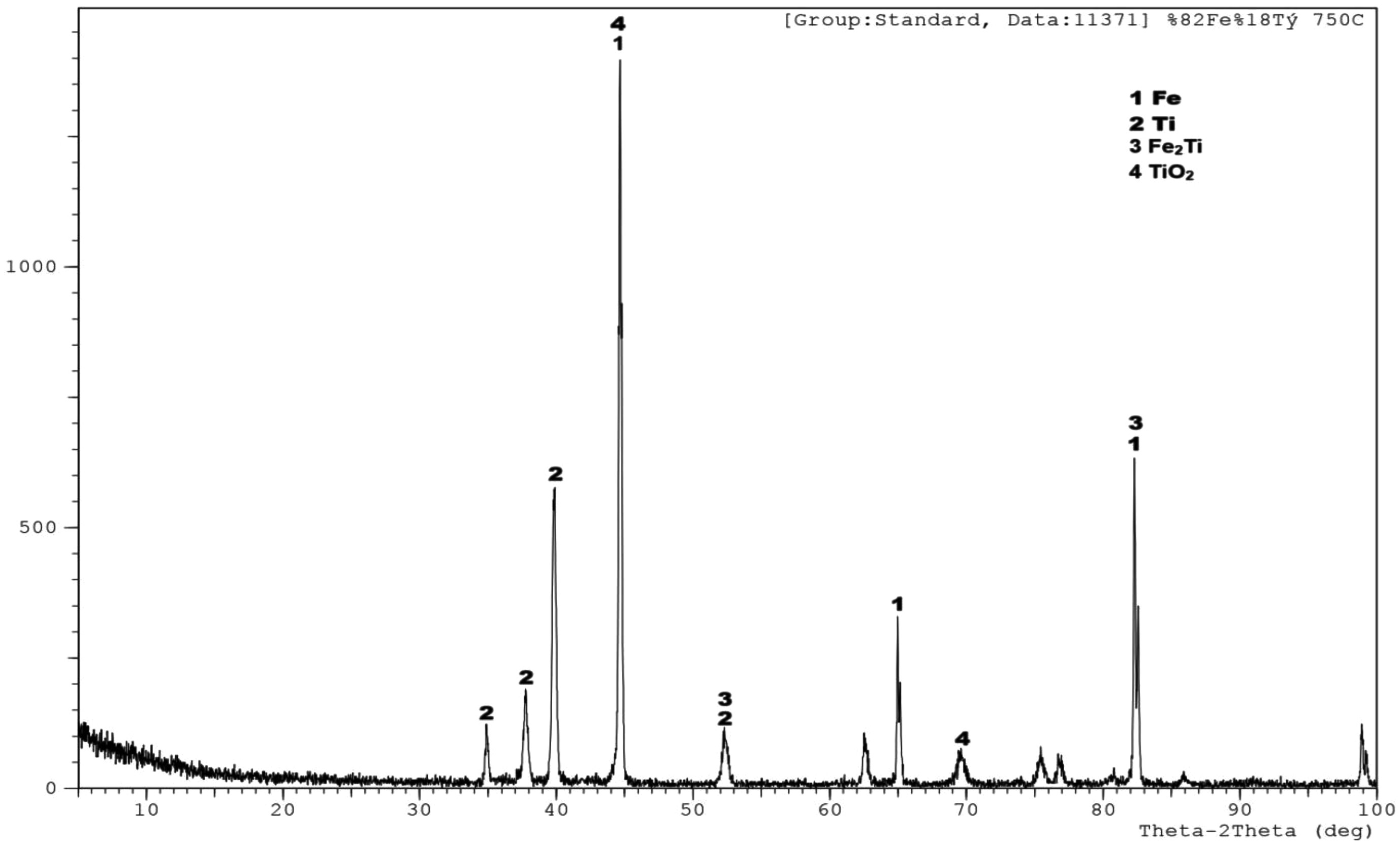

The X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis of the alloy with a composition of 82% Fe and 18% Ti, heat-treated at 750 °C, reveals the formation of multiple crystalline phases (Fig. 5). The most intense peak, observed around 45°, corresponds to iron (Fe), indicating that Fe is the dominant phase in the microstructure, which is consistent with its high concentration in the alloy. Several smaller peaks appearing in the 35°–40° range suggest the presence of titanium (Ti) as a separate crystalline phase. Additionally, distinct peaks around 50° and 80° indicate the formation of the intermetallic compound Fe₂Ti, which typically forms through solid-state diffusion at elevated temperatures. The presence of this intermetallic phase is significant, as it can enhance the mechanical properties of the alloy, particularly hardness and high-temperature strength. A weak peak around 70° is attributed to titanium dioxide (TiO₂), likely resulting from slight surface oxidation during the heat treatment process. This oxide layer may act as a protective film on the material’s surface. Overall, the analysis confirms that the alloy consists of a dominant Fe matrix with dispersed Ti and Fe₂Ti phases, along with a minor amount of surface TiO₂. This phase composition provides valuable insights into the thermal stability and structural characteristics of the alloy.

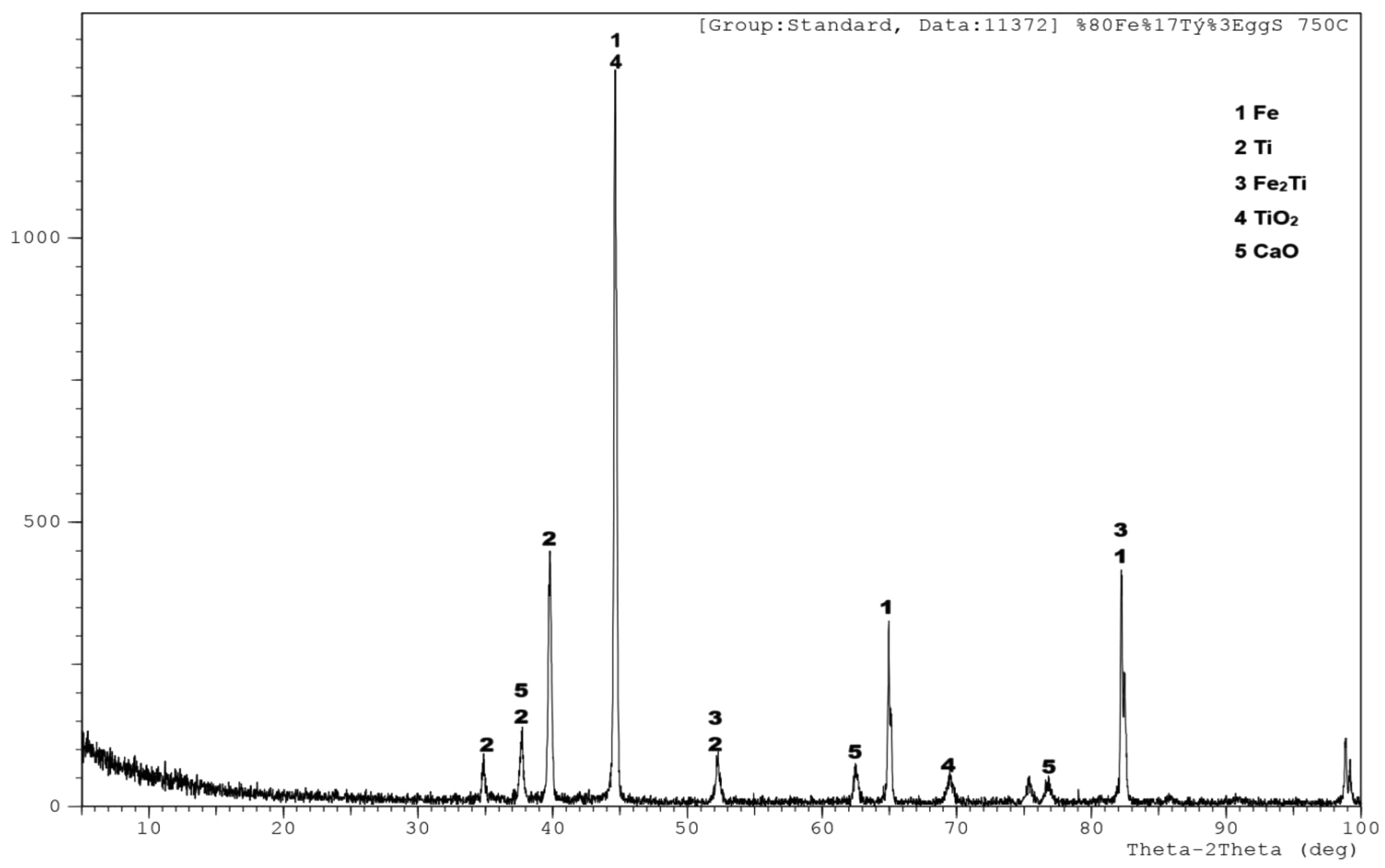

The diffraction pattern reveals a multiphase structure after heat treatment at 750 °C (Fig. 6). The most intense peak, located around 45°, corresponds to the Fe phase, indicating that iron remains the dominant crystalline phase. This is consistent with the high Fe content (80%) in the sample. Several peaks observed between 35° and 40° are attributed to titanium (Ti), suggesting the presence of separate Ti crystalline phases distributed within the structure. Distinct peaks around 50° and 80° correspond to the Fe₂Ti intermetallic phase, which typically forms through diffusion between Fe and Ti at elevated temperatures. This phase is known to enhance the alloy’s hardness and high-temperature mechanical performance. The presence of calcium oxide (CaO), originating from the thermal decomposition of eggshell-derived CaCO₃, is confirmed by moderate-intensity peaks labeled as phase 5. These peaks suggest that CaO is incorporated as a stable ceramic phase in the microstructure. Additionally, a weak TiO₂ peak near 70° indicates partial oxidation of titanium during heat treatment, potentially forming a thin oxide layer on the surface.

The X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis of the sample composed of 72% Fe, 15% Ti, and 13% eggshell (presumably as a CaCO₃ source) heat-treated at 750 °C reveals the formation of five distinct phases Fig. 7). The most intense diffraction peak, located around 45°, corresponds to Fe (iron), indicating that iron remains the dominant matrix phase in the microstructure, which is consistent with its high concentration in the alloy. Prominent peaks between 35° and 40° are attributed to Ti (titanium), suggesting the presence of separate Ti crystalline phases. Peaks around 50° and 80° confirm the formation of the Fe₂Ti intermetallic phase, which typically develops through solid-state diffusion between Fe and Ti at elevated temperatures. This intermetallic compound can significantly improve mechanical properties such as hardness and high-temperature strength. Due to the presence of eggshell-derived CaCO₃, thermal decomposition at 750 °C likely resulted in the formation of CaO (calcium oxide), evidenced by multiple low-to-medium intensity peaks labeled as phase 5 across the 30°–80° 2θ range. This confirms that CaO is retained in the structure as a stable oxide phase. Additionally, a weak TiO₂ peak around 70° indicates limited surface oxidation, possibly forming a thin oxide layer. In addition, the potential formation of Ca–Ti–O compounds such as CaTiO₃ was also considered due to the thermal decomposition of eggshell-derived CaCO₃ into CaO during sintering. However, no distinct diffraction peaks corresponding to CaTiO₃ or related ternary oxides were detected in the XRD patterns of the sintered samples. This absence can be attributed to the relatively low sintering temperature (750 °C) and the use of an inert argon atmosphere, which limited the interdiffusion between CaO and Ti. At higher sintering temperatures or under slightly oxidative conditions, the formation of CaTiO₃ could become thermodynamically favorable, potentially influencing both the hardness and densification behavior of the composites. This possibility will be further investigated in future studies to clarify the role of Ca–Ti–O secondary phases in the Fe–Ti–Eggshell system.

|

Fig. 1 Density, Porosity and Microhadness curves. |

|

Fig. 2 SEM photographs of sintered samples. |

|

Fig. 3 EDX analysis of the SP1 sample sintered at 750 ᵒC. |

|

Fig. 4 EDX analysis of the SP6 sample sintered at 750 ᵒC. |

|

Fig. 5 XRD analysis of sample (%82Fe-%18Ti) sintered at 750 ºC. |

|

Fig. 6 XRD analysis of sample (%80Fe-%17Ti-%3EggShell) sintered at 750 ºC. |

|

Fig. 7 XRD analysis of sample (%72Fe-%15Ti-%13EggShell) sintered at 750 ºC. |

In this study, the physical and mechanical properties of Fe–Ti matrix composites reinforced with varying amounts of eggshell powder and sintered at 750 °C under an argon atmosphere were systematically investigated. The results revealed that increasing the eggshell content led to a significant reduction in both density and microhardness. This trend can be attributed to the inherently low density and limited mechanical strength of eggshells as a bioceramic material. While porosity decreased at lower reinforcement levels, it increased again at higher eggshell contents, suggesting enhanced sintering efficiency at small additions and weakened particle bonding as the eggshell ratio rose. Although eggshell powder offers ecological and economic advantages, optimizing its content is essential to preserve the structural integrity and mechanical performance of the composites.

Based on the quantitative evaluation, the optimum balance between density and microhardness was achieved at approximately 3 wt.% eggshell addition. At this reinforcement level, the composite exhibited improved densification and sufficient mechanical strength while maintaining a reduced overall density. Further additions (≥ 8 wt.%) resulted in excessive porosity and decreased hardness due to weakened particle bonding and the agglomeration of ceramic phases. Therefore, 3 wt.% eggshell can be considered the most effective reinforcement level for achieving a desirable combination of lightness and mechanical integrity in Fe–Ti–Eggshell composites.

SEM micrographs of Fe–Ti matrix composites with varying eggshell content (Fig. 3) demonstrate distinct changes in microstructure based on the reinforcement level. The unreinforced sample (82Fe–18Ti) displays a dense and compact structure with well-sintered particles and minimal porosity, indicating effective densification. Upon the addition of 3 wt.% eggshell (80Fe–17Ti–3%Eggshell), a slight increase in porosity and more pronounced particle boundaries become evident, signaling the onset of reduced sintering efficiency. With further increases to 5.5 wt.% and 8 wt.%, the microstructure becomes noticeably more porous and less cohesive, characterized by visible interparticle voids and weaker bonding. At the highest reinforcement levels of 10 wt.% and 13 wt.%, the micrographs reveal severe porosity, particle detachment, and agglomeration, indicating a pronounced deterioration in sintering quality. These structural degradations correlate with the observed declines in density and microhardness.

XRD analyses further support these findings. As shown in Fig. 4, four main phases—Fe, Ti, Fe₂Ti, and TiO₂—were identified in the 82% Fe–18% Ti alloy heat-treated at 750 °C. Notably, the Fe₂Ti intermetallic phase contributes significantly to the mechanical and physical properties of the material. In the 80Fe–17Ti–3%Eggshell sample (Fig. 5), the XRD pattern reveals a dominant Fe matrix with secondary Ti and Fe₂Ti phases, along with minor CaO and TiO₂ phases. The emergence of CaO results from the thermal decomposition of eggshell-derived CaCO₃. Similarly, in samples with higher eggshell content (Fig. 6), the presence of CaO and Fe₂Ti intermetallics contributes to a complex multiphase structure. This composition may enhance mechanical strength, oxidation resistance, and thermal stability, making these composites potentially suitable for high-temperature or structural applications.

Considering the promising outcomes obtained in terms of lightweight structure and phase stability, Fe–Ti–Eggshell composites can be envisioned for various potential applications. Their reduced density and the presence of CaO and Fe₂Ti phases make them suitable candidates for corrosion-resistant coatings, thermal barrier layers, and lightweight structural components in engineering systems. Moreover, due to the biocompatibility potential imparted by eggshell-derived CaO, these composites may also find use in biomedical applications such as dental implants, prosthetic frameworks, or bone-interfacing components, where both mechanical integrity and biofunctionality are essential.

The detected TiO₂ phase was mainly localized at the particle boundaries, suggesting surface oxidation rather than a homogeneous oxide distribution within the Fe–Ti matrix. Although quantitative pore morphology analysis was not performed, SEM micrographs indicate that the type of porosity changes with increasing eggshell content. At lower reinforcement levels (≤ 3 wt.%), pores appear mostly closed and isolated, suggesting efficient sintering and compact particle bonding. In contrast, at higher reinforcement levels (≥ 8 wt.%), the porosity becomes more open and interconnected, likely facilitating gas entrapment and reducing mechanical integrity. This transition from closed to open porosity is consistent with the observed decrease in hardness and densification efficiency at higher eggshell additions.

As a result, Fe–Ti matrix composites reinforced with eggshell powder and sintered at 750 °C show that increasing eggshell content reduces density and microhardness due to higher porosity and weaker particle bonding. XRD and SEM analyses confirm the formation of Fe, Ti, Fe₂Ti, TiO₂, and CaO phases. While eggshell provides ecological benefits, its content must be optimized to maintain structural and mechanical performance. At higher reinforcement levels, the thermal decomposition of eggshell-derived CaCO₃ produces CaO as a stable ceramic phase dispersed within the Fe–Ti matrix. Although CaO does not directly participate in chemical reactions with Fe or Ti to form intermetallic compounds under the sintering conditions (750 °C, inert atmosphere), it indirectly influences the formation of the Fe₂Ti phase through microstructural and kinetic effects. The presence of CaO increases porosity and decreases sintering efficiency, as evidenced by SEM micrographs showing weaker particle bonding and higher void content in samples containing 10–13 wt.% eggshell. Such structural degradation limits the diffusion pathways between Fe and Ti particles, thereby suppressing the solid-state diffusion required for Fe₂Ti intermetallic phase development. Additionally, the ceramic CaO particles may act as diffusion barriers at grain boundaries, reducing Fe–Ti interfacial contact and delaying the intermetallic reaction. Consequently, although the Fe₂Ti phase remains detectable in XRD analyses, its relative peak intensity decreases with increasing CaO content, indicating a lower fraction of this phase. Overall, the influence of CaO on Fe₂Ti formation is predominantly physical and kinetic rather than chemical in nature.

To further substantiate the interpretation of densification behavior, it would be highly beneficial to include precise quantitative porosity values in addition to the qualitative SEM observations. Reporting these numerical porosity measurements would enable a more accurate correlation between the eggshell reinforcement ratio, sintering efficiency, and resulting microstructural evolution. Such quantitative data would significantly enhance the analytical depth and strengthen the reliability of the conclusions drawn regarding the influence of eggshell addition on the Fe–Ti matrix composites. It should be noted that Vickers microhardness was the only mechanical test conducted in this study. While it provides valuable insights into local mechanical behavior, additional evaluations—such as compressive strength, flexural strength, and fracture toughness—would offer a more complete understanding of the composite’s overall structural integrity. These measurements are planned for future studies to establish stronger correlations between microstructure and macroscopic mechanical performance.

- 1. S. Ozan, J. Lin, Y. Zhang, Y. Li, and C. Wen, J. Mater. Res. Technol. 9[2] (2020) 2308-2318.

-

- 2. M. Surappa, Sadhana, 28[1] (2003) 319-334.

-

- 3. L. Teng, W. Li, and F. Wang, J. Alloys Compd. 319[1-2] (2001) 228-232.

-

- 4. H. Tsukamoto, T. Kunimine, M. Yamada, H. Sato, and Y. Watanabe, Key Eng. Mater. 520 (2012) 269-275.

-

- 5. B. Basu, J. Vleugels, and O. Van der Biest, J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 25[16] (2005) 3629-3637.

-

- 6. C. Han, Y. Li, X. Liang, L. Chen, N. Zhao, and X. Zhu, Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 22[8] (2012) 1855-1859.

-

- 7. K.-H. Lee, S.-H. Ahn, and K.-W. Nam, J. Ceram. Process. Res. 19[3] (2018) 183-188.

-

- 8. D.K. Rajak, D.D. Pagar, P.L. Menezes, and E. Linul, Polymers 11[10] (2019) 1667.

-

- 9. S. Kumar and R. Balasubramanian, Mater. Sci. Eng. A 670 (2016) 25-35.

- 10. M. Awais, H. Raza, and A. Raza, J. Alloys Compd. 815 (2020) 152315.

-

- 11. T. Gyawali, Y. Li, and C. Wen, Acta Biomater. 84 (2019) 414-427.

- 12. A. Arunkumar and K. Senthil Kumar, Compos. Part B 175 (2019) 107110.

- 13. S. Rittidech, N. Tongsri, and P. Charoensuk, Ceram. Int. 44[6] (2018) 6481-6490.

- 14. F. Dong, J. Zhang, and Y. Li, J. Mater. Res. 33[14] (2018) 2020-2032.

- 15. A. Jeong, S.-H. Lee, and K.-M. Kim, J. Ceram. Process. Res. 21[5] (2020) 512-519.

- 16. L. Pérez, M. Laguna, and J.L. García, Mater. Des. 198 (2021) 109350.

- 17. R.S. Razavi and A. Eghbali, Mater. Chem. Phys. 240 (2020) 122176.

- 18. P. Singh and S. Prasad, J. Compos. Mater. 54[10] (2020) 1303-1314.

- 19. M.A. El-Amoush, Mater. Lett. 62[20] (2008) 3381-3384.

- 20. G. Lütjering and J.C. Williams, Titanium, Springer (2007) 121-178.

-

- 21. C. Leyens and M. Peters, Titanium and Titanium Alloys, Wiley-VCH (2003) 45-97.

-

- 22. M. Niinomi, Mater. Sci. Eng. A 243 (1998) 231-236.

-

- 23. G. Henriques and M. N. Nobilo, J. Prosthet. Dent. 88[3] (2002) 302-308.

- 24. K. Senthil and S. Arunkumar, J. Green Eng. 8 (2018) 317-330.

- 25. A.U. Kalu and J.M. Akpan, Int. J. Eng. Res. 7[4] (2019) 72-78.

- 26. S.K. Nayak and S. Mohanty, Compos. Part A 32 (2001) 739-748.

- 27. F. Watari and A. Yokoyama, Mater. Trans. 43[12] (2002) 2978-2987.

- 28. Y. Li and C. Wen, J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 102[10] (2014) 3615-3625.

- 29. S. Banerjee and P. Mukhopadhyay, Phase Transformations, Elsevier (2007) 300-336.

-

This Article

This Article

-

2025; 26(6): 1000-1008

Published on Dec 31, 2025

- 10.36410/jcpr.2025.26.6.1000

- Received on Aug 3, 2025

- Revised on Oct 16, 2025

- Accepted on Nov 6, 2025

Services

Services

Shared

Correspondence to

Correspondence to

- Aslı Betül Yönetken

-

Ankara Yıldırım Beyazıt University,Faculty of Dentistry,Department of Prosthodontics, Yayla Mahallesi Yozgat Bulvarı, 1487. Cadde No:55 Keçiören / Ankara, Türkiye

Tel : +90 312 906 1000 Fax: +90 312 906 2950 - E-mail: abyonetken@aybu.edu.tr, yonetken@aku.edu.tr

Copyright 2019 International Orgranization for Ceramic Processing. All rights reserved.

Copyright 2019 International Orgranization for Ceramic Processing. All rights reserved.