- Effect of LiF addition on the sinterability, crystal structure and microwave dielectric properties of Li3Mg4NbO8 ceramics

Wei Jin, Jingjing Tan, Jiaxin Yan, Yao Tao, Ningning Yao, Xiaomeng Ruan and Cuijin Pei*

School of Science, Xi’an University of Posts and Telecommunications, Xi’an 710121, China

This article is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

The normative solid-state reaction process was adopted to prepare Li3Mg4NbO8 ceramics with LiF addition. We investigated the impacts of LiF additive on the crystal structure, sinterabillity as well as dielectric performance at microwave region of the Li3Mg4NbO8-basic ceramics. XRD analysis confirmed that the addition of LiF to Li3Mg4NbO8 lead to the formation of new phase Li4Mg4NbO8F with cubic rock salt structure. The densified temperature of Li3Mg4NbO8-basic ceramics could be effectively reduced from 1150 oC to 900 oC with LiF addition. Both the permitivity (εr) and quality factor (Qf) of present ceramics were is closely correlated with the bulk density and cell volume. The 900 oC-sintered Li3Mg4NbO8-basic ceramics owned excellent chemical compatibility with silver and optimized microwave dielectric performance (εr ~13. 4, Qf ~ 32,400 GHz at 9.4 GHz, and temperature coefficient of resonant frequency (τf) ~ -43.0 ppm/℃

Keywords: Ceramics, Li3Mg4NbO8, crystal structure, microwave dielectric properties

With the arrival of 5G communication systems, more attention has been attracted to microwave dielectric ceramics, which is extensively applied in modern communication field. Meanwhile, a series of sintering synthetic approaches, for example the cold sintering process and low-temperature co-fired ceramic (LTCC) technology, furnish technical support to produce the multi-functional, and miniaturized passive microwave devices [1-4]. Thus, the dielectric ceramics applied in 5G and LTCC technologies must fulfill the following essential basic characteristics: low firing temperature (≤960 oC), good dielectric performance as well as low-cost and environmental friendly [5]. At present, a great number of studies were taken to lower the sintering temperature of existing ceramics or exploit novel ceramic systems with good microwave dielectric performance and low firing temperature [6-10].

Recently, rock salt structural Li2O-MgO-Nb2O5 system ceramics have drawn great attentions due to their in- triguing dielectric and luminescence performance [11-14]. More recently, our group reported the microwave dielectric performance of a new phase (Li3Mg4NbO8) in Li2O-MgO-Nb2O5 system [15]. However, the major challenge of Li3Mg4NbO8 ceramics is its high sintering temperature, which impeded its practical use to some extent, especially in LTCC technology. Usually, the reduction of sintering temperature of ceramics could be achieved by two methods: viz. (i) Using highly active nanopowders synthesized by wet chemical route. (ii) Adding sintering aid with low melting point [16]. Among them sintering aid addition is the most economical and effective approach [17]. It is reported that LiF is an effective firing additive for reducing the sintering temperature of many ceramics due to its low melting point of 848 oC [18-20]. What's more, LiF with other oxides materials (Li2TiO3, Li3NbO4, Li3Mg2NbO6) with the same rock salt structure can easily form a new oxy- fluoride compound, which can facilitate a remarkable decrease in the sintering temperature of the oxides materials [21-23]. In present paper, the LiF was selected to make the Li3Mg4NbO8 ceramic be used as a LTCC material. Then we examined systematically the impacts of LiF on the crystal phase constitution, firing behavior, microstructures, microwave dielectric characterization, and chemical compatibility with silver of Li3Mg4NbO8 ceramics.

The Li3Mg4NbO8-LiF ceramics were elaborated through the normative process route of solid-state reaction. The high purity powders (LiF, Li2CO3, MgO, Nb2O5) were weighed according to stoichiometric Li3Mg4NbO8, and pre-milled for 8 h using alcohol and zirconia balls as grinding media. The dried slurries were pre-sintered at 1000 oC during 4 h in order to form the Li3Mg4NbO8 phase. Subsequently, Li3Mg4NbO8-LiF mixture powders were re-milled for 8 h. Green discs (Ф10×5 mm) were prepared with a pressure of 100 MPa and using the mixture of Li3Mg4NbO8-LiF mechanically milled powders and Polyvinyl alcohol (6 wt%). These discs were fired at 850-950 oC for 5 h in air.

Phase assemblages for Li3Mg4NbO8-LiF ceramics were analyzed by Powder X-ray diffraction (XRD, Smartlab, Japan). Use the Hitachi SU3800 scanning electron microscope to observe the microstructures of Li3Mg4NbO8-LiF ceramics. The bulk densities of present ceramics were measured through the method of Archimedes. Use Rohde & Schwarz ZNB20 vector network analyzer and resonant cavity method to measure the dielectric performance (εr, Qf) of Li3Mg4NbO8-LiF sintered bodies at around 9-10 GHz. The τf value was calculated using the following formula (1).

where f80 and f20 mean the measured frequency under 80 and 20 oC, respectively.

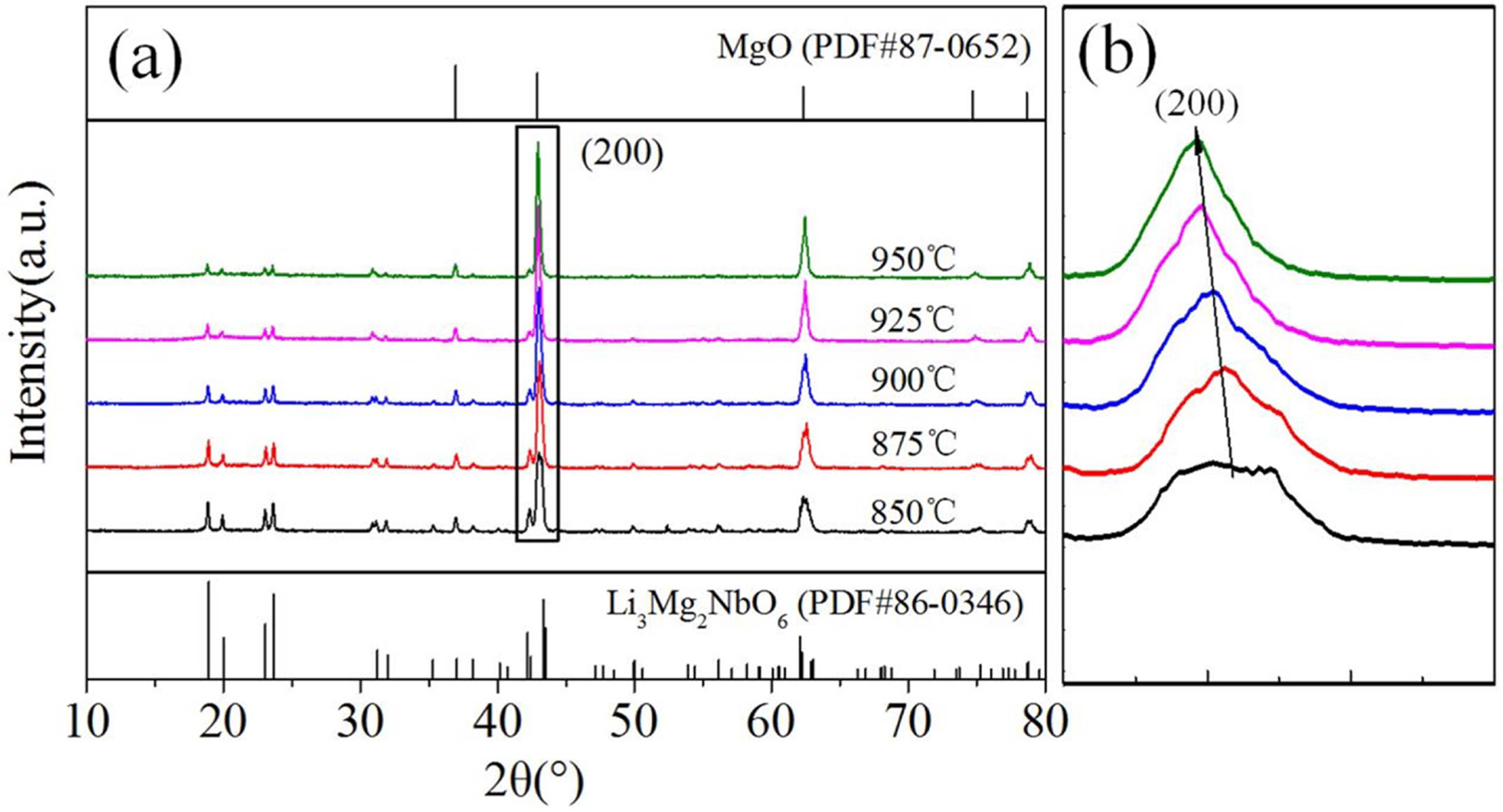

Fig. 1 displays the XRD profiles for Li3Mg4NbO8-LiF samples fired at 850-950 oC. The major diffraction peaks can be ascribed to the standard diffraction lines of cubic-type MgO (PDF#87-0651) phase rock salt structure, while the other diffraction peaks can well indexed to orthorhombic-type Li3Mg4NbO8 phase rock salt structure. And no obvious LiF or impurity phase was formed, except for the cubic and orthorhombic (Li3Mg4NbO8) phases, indicating that LiF diffused into the orthorhombic structure phase Li3Mg4NbO8 and formed the new phase (Li4Mg4NbO8F) with cubic structure. The similar phenomenon was also found in previous researches [23]. The cubic type structure is the consequence of a disordered sub-cell of the orthorhombic superstructure [24]. In addition, the enlarged main peak (200) moved to lower angle with rising sintering temperature as illustrated in Fig. 1(b), indicating anexpansion of cell volume based on the Bragg equation (2d sinθ = nλ).

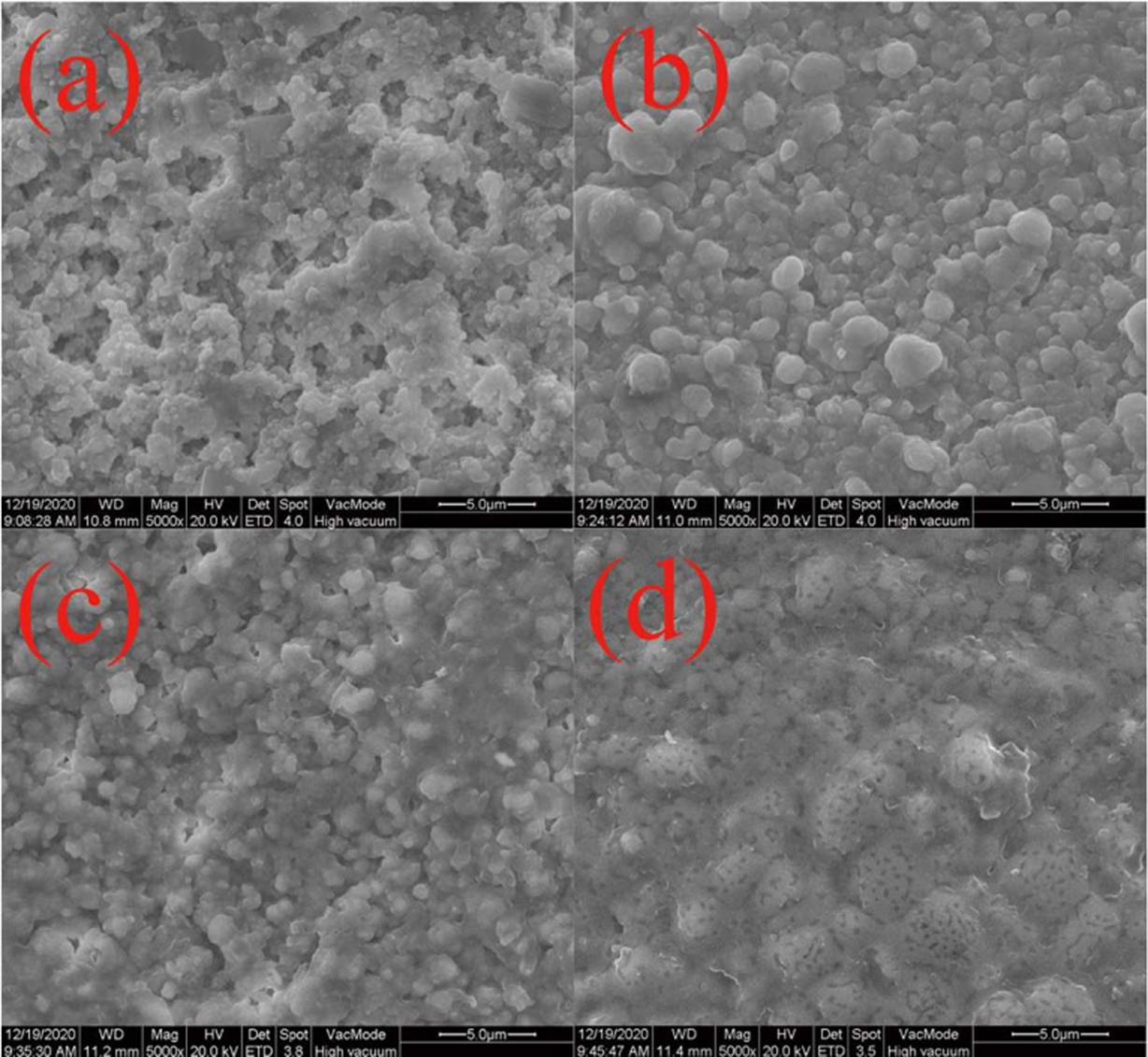

Typical surface SEM images for Li3Mg4NbO8-LiF ceramics fired at 875-950 oC are displayed in Fig. 2. Some open pores were observed for the samples fired below 900 oC, as seen in Figs. 2(a) and (b). With the enhancement of firing temperature, the open pores gradually decrease and a relative compact and homo- geneous microstructure were obtained for the specimen fired at 900 oC (Fig. 2(b)). However, when the firing temperature exceeded 925 oC, partial grains begin to melt due to over-firing as seen in Figs. 2(c) and (d), which inevitably affects the bulk density and dielectric performance of investigated ceramics [25].

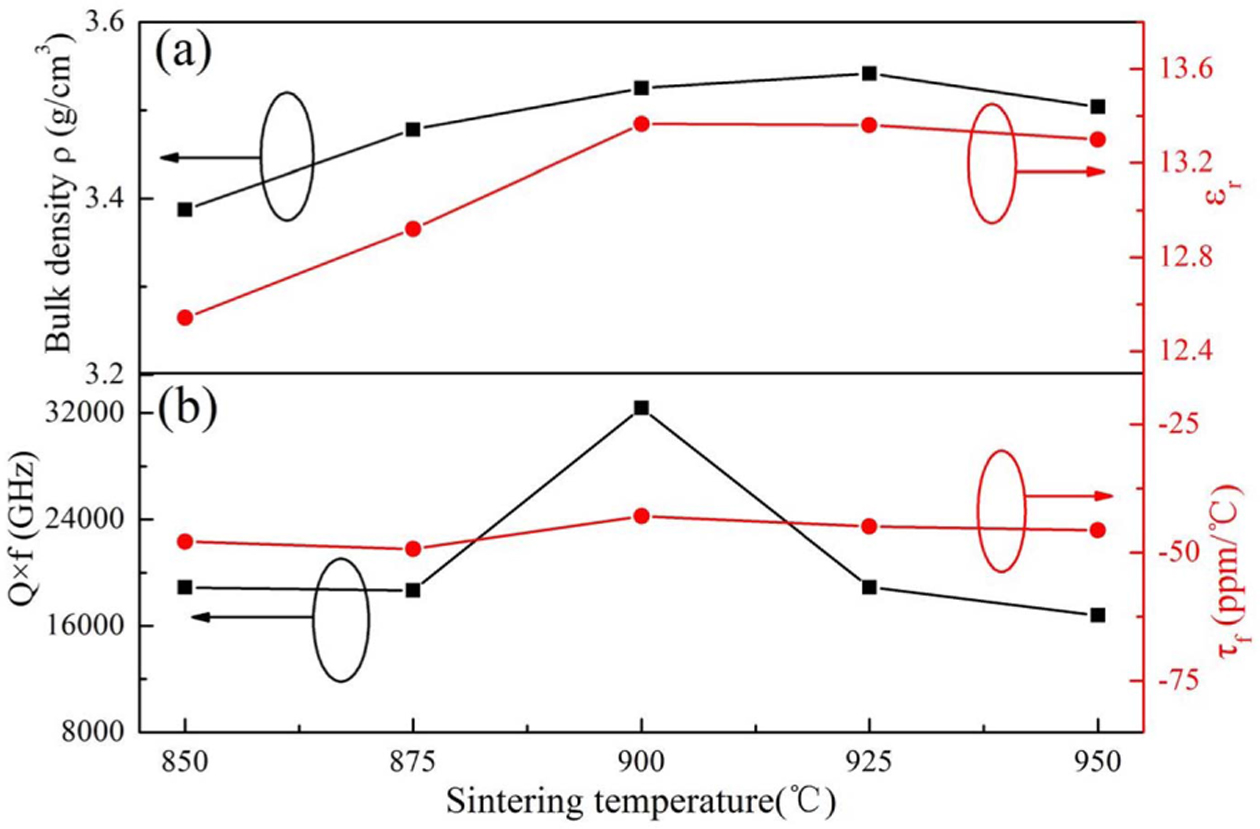

Fig. 3 presents the dependence of bulk density (ρ), εr, Qf and τf on sintering temperature for Li3Mg4NbO8-LiF specimens. With enhancing firing temperature from 850 to 925 oC, the ρ enhanced gradually from 3.387 to 3.542 g/cm3, but then declined to 3.50 g/cm3 at 950 oC. The elevating sintering temperature can simultaneously cause contradictory effects that are attributed to an enhanced ρ due to the confined porosity and related to a decreased ρ due to over-sintering associated with the partial grains melting mentioned before. From the view point of ρ, the firing temperature of the Li3Mg4NbO8-basic ceramics was markedly reduce from 1150 oC to 925 oC with the additive of LiF [15]. LiF diffused into the Li3Mg4NbO8 lattice, which reduced the chemical potential of Li3Mg4NbO8. The combination of the for- mation of low melting point liquid phase during sintering process and the alleviation of chemical potential was responsible for the low temperature sintering of the Li3Mg4NbO8-LiF system [26]. As illustrated in Fig. 3(b), both the εr and Qf values for Li3Mg4NbO8-LiF ceramics rose initially, achieved a peak at 900 oC and thereafter decreased with rising firing temperature. The variations were somewhat inconsistent with of bulk density, implying that except ρ, other factors impacting the εr and Qf values should be considered. Generally, the εr is associated with the presence of secondary phase, bulk density, mean ionic polarization (αtheo/Vm) [27]. From Fig. 1, there was no secondary phase in all samples, but the cell volume (Vm) increased as rising firing temperature and thus resulted in the decline of αtheo/Vm. Therefore, the variation of εr could be explained by the competing results of bulk density and αtheo/Vm. Regarding Qf: it is tightly connected with the packing fraction (P.F.) and density. High P.F. corresponds to the weak lattice vibration and thus high Qf value [28]. In this work, with increasing temperature the P.F. decreased due to the enhanced cell volume ( Fig. 1(b)) based on the formula (2).

Thus, the variation of Qf for present ceramics could be ascribed to the combined effects of bulk density and P.F.

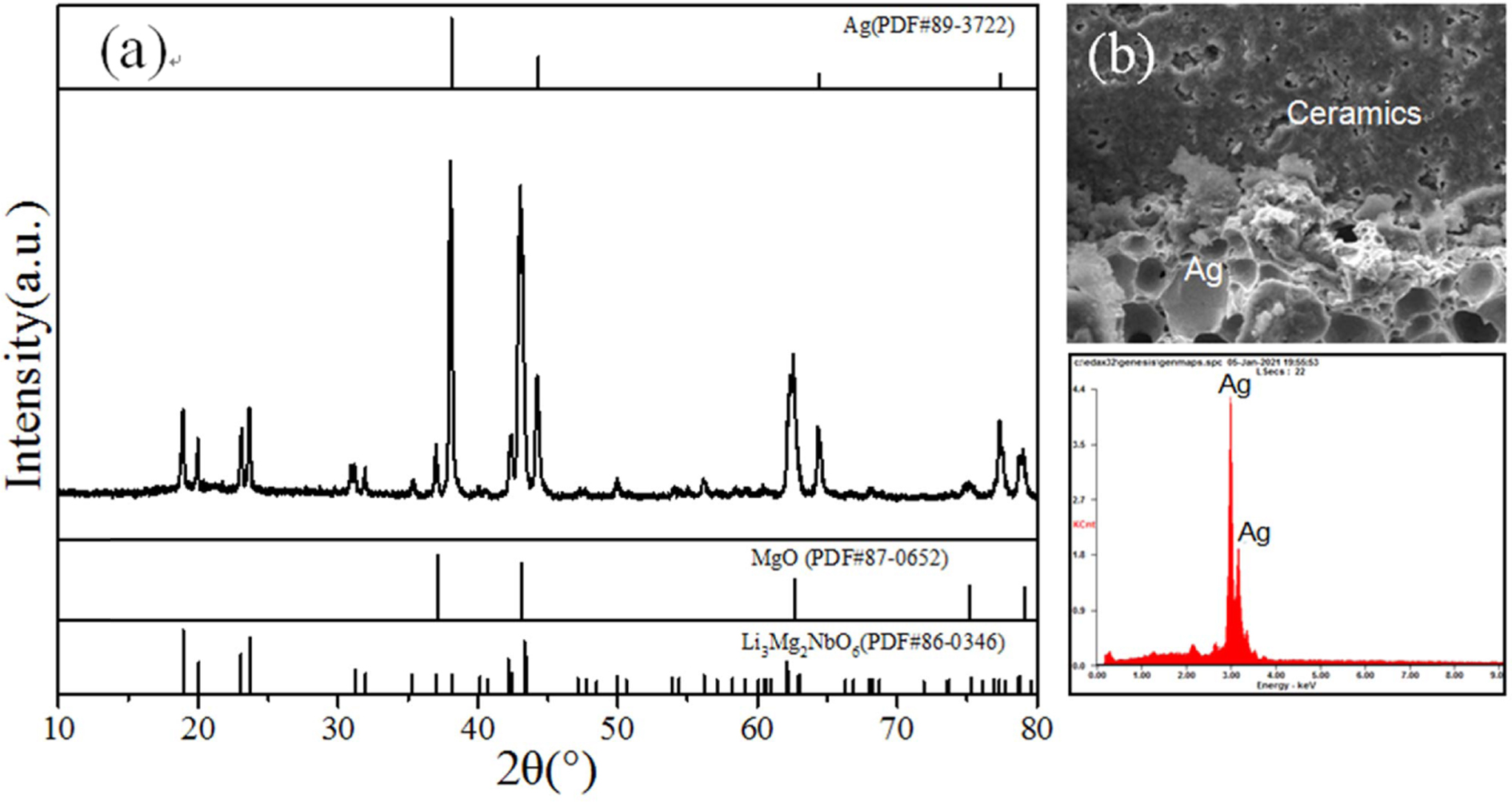

To evaluate its potential applications in LTCC tech- nology, the chemical compatibility between Ag elec- trode and Li3Mg4NbO8-LiF ceramics was investigated. Fig. 4 exhibits the results of XRD profile as well as SEM-EDS of Li3Mg4NbO8-LiF with 20 wt% Ag addition sintered at 900 oC. The XRD pattern in Fig. 4 shown that only diffraction peaks for Li4Mg4NbO8F/Li3Mg4NbO8 and Ag (JCPDS# 89-3722) phases were detected, indicating no chemical reaction occurred between Li3Mg4NbO8 and Ag. In addition, from the insert of Fig. 4, the clear interface and relatively tightly bonded between Li3Mg4NbO8-LiF and Ag phases were observed, indicating no diffusion occurred between them during the firing process. These results demonstrated that the Li3Mg4NbO8-LiF ceramics exhibited excellent Ag-cofiring chemical compatibility and thus is a potential candidate for LTCC applications.

|

Fig. 1 (a) XRD patterns of Li3Mg4NbO8-LiF ceramics sintered at different temperatures, (b) enlarged view of the (200) peak. |

|

Fig. 2 SEM images of Li3Mg4NbO8-LiF ceramics sintered at different temperatures: (a) 875 oC, (b) 900 oC, (c) 925 oC, (d) 950 oC. |

|

Fig. 3 The bulk density (ρ), εr, Qf and τf values of Li3Mg4NbO8- LiF ceramics sintered at 850-950 oC. |

|

Fig. 4 (a) XRD, (b) fracture SEM-EDS analysis of Li3Mg4NbO8-LiF ceramics co-fired with 20 wt% Ag powders at 900 oC. |

The influences of LiF doping on the sintering behavior, crystal phase constitution, and dielectric performance at microwave frequency for Li3Mg4NbO8 had been re- searched. The doping of LiF significantly lowed its densification temperature of Li3Mg4NbO8-basic ceramics. The mixed cubic (Li4Mg4NbO8F) and orthorhombic (Li3Mg4NbO8) phases with rock salt structure were revealed via XRD analysis. Both the Qf and εr values were strongly depended on the cell volume and bulk density of ceramics. The Li4Mg4NbO8F-Li3Mg4NbO8 ceramics fired under 900 oC owned optimized dielectric performance at about 9.4 GHz (Qf = 32,400 GHz, εr = 13. 4, τf = -43.0 ppm/℃) along with good Ag-cofiring chemical compatibility, suggesting it a latent material for LTCC applications.

The authors acknowledge supports from National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No 52002317), Shaanxi Province Natural Science Foun- dation, China (Grant No. 2021JM-458), and Xi'an Science and technology Bureau (GXYD17.19).

- 1. C.J. Pei, J.J. Tan, Y. Li, G.G. Yao, Y.M. Jia, Z.Y. Ren, P. Liu, and H.W. Zhang, J. Adv. Ceram. 9[5] (2020) 588-594.

-

- 2. X. Zhang, Z. Jiang, B. Tang, Z.X. Fang, Z. Xiong, H. Li, C.L. Yuan, and S.R. Zhang, Ceram. Int. 46[8] (2020) 10332-10340.

-

- 3. S. Zhang, and R. Zuo, J. Alloys. Compd. 832 (2020) 154946.

-

- 4. S.Z. Hao, D. Zhou, F. Hussain, J.Z. Su, W.F. Liu, D.W. Wang, Q.P. Wang, and Z.M. Qi, J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 103[12] (2020) 7259-7266.

-

- 5. P. Zhang, M. Yang, M. Xiao, and Z.J. Zheng, Mater. Chem. Phys. 236 (2019) 121805.

-

- 6. G. Wang, H. Zhang, X. Huang, F. Xu, Y.M. Lai, G. Gan, Y. Yang, C. Liu, J. Li, and L.C. Jin, Mater. Lett. 235 (2019) 84-87.

-

- 7. C.J. Pei, G.G. Yao, Z.Y. Ren, J. Ceram. Process. Res. 17[7] (2016) 681-684.

- 8. T. Qin, C. Zhong, B. Tang, and S.R. Zhang, J. Eur Ceram. Soc. 41[2] (2021) 1342-1351.

-

- 9. Z.B. Feng, B.J. Tao, W.F. Wang, H.Y. Liu, H.T. Wu, and Z.L. Zhang, J. Alloys. Compd. 822 (2020) 153634.

-

- 10. G.G. Yao, Y. Li, J.J. Tan, C. Pei, Y. Zhang, and J. Chen, J. Ceram. Process. Res. 21[3] (2020) 338-342.

-

- 11. M. Castellanos, J. Gard, and A.R. West, J. Appl. Cryst. 15[1] (1982) 116-119.

-

- 12. L. Yuan, and J.J. Bian, Ferroelectrics. 387[1] (2009) 123-129.

-

- 13. J. Li, Z.W. Zhang, Y.F. Tian, L.Y. Ao, J.Q. Chen, A.H. Yang, C.X. Su, L.J. Liu, Y. Tang, and L. Fang, J. Mater. Sci. 55[33] (2020) 15643-15652.

-

- 14. X.C. Wang, X.P. Zhou, Y.X. Cao, Q. Wei, Z.Y. Zhao, and Y.H. Wang, J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 102[11] (2019) 6724-6731.

-

- 15. G.G. Yao, J.X. Yan, J.J. Tan, C.J. Pei, P. Liu, H.W. Zhang, and D.W. Wang, J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 41[13] (2021) 6490-6494.

-

- 16. Y Zhan, L.X. Li, and M.K. Du, Ceram. Int. 47[19] (2021) 27462-27468.

-

- 17. M.A. Sanoj, C.P. Reshmi, and M.R. Varma, J. Am. Ceram. Soc., 92 [11] (2009) 2648-2653.

-

- 18. G. Wang, D. Zhang, Y. Lai, X. Huang, Y. Yang, G. Gan, F. Xu, Q. Wang, J. Li, C. Liu, L. Jin, Y. Liao, and H. Zhang, J. Alloys Compd. 782 (2019) 370-374.

-

- 19. P. Zhang, S.X. Wu, Y.G. Zhao, and M. Xiao, Mater. Chem. Phys. 222 (2019) 246-250.

-

- 20. Z.F. Fu, C. Li, J.L. Ma, and Y. Wu, Mater. Sci. Eng. B. 250 (2019) 114438.

-

- 21. X. Chu, J. Jiang, J.Z. Wang, Y.C. Wu, L. Gan and T.J. Zhang, Ceram. Int. 47[3] (2021) 4344-4351.

- 22. Z. Zhang, Y. Tang, H. Xiang, A. Yang, Y. Wang, C. Yin, Y. Tian, and L. Fang, J. Mater. Sci. 55[1] (2020) 107-115.

-

- 23. S.M. Zhai, P. Liu, S.S. Zhang, J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 41[8] (2021) 4478-4483.

-

- 24. X. Zhang, B. Tang, Z. Fang, H. Yang, Z. Xiong, L. Xue, and S. Zhang, Inorg. Chem. Front. 5[12] (2018) 3113-3125.

-

- 25. C.J. Pei, C.D. Hou, Y. Li, G.G. Yao, Z.Y. Ren, P. Liu, and H.W. Zhang, J. Alloys. Compd. 792 (2019) 46-49.

-

- 26. G.G. Yao, J.J, Tan, J.X. Yan, M.Q. Liu, C.J. Pei, and Y.M. Jia, Ceram. Int. 47[19] (2021) 27406-27410.

-

- 27. M.K. Du, L.X. Li, S.H. Yu, Z. Sun, and J.L. Qiao, J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 101[9] (2018) 4066-4075.

-

- 28. E.S. Kim, B.S. Chun, R. Freer, and R.J. Cernik, J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 30[7] (2010) 1731-1736.

-

This Article

This Article

-

2021; 22(6): 675-678

Published on Dec 31, 2021

- 10.36410/jcpr.2021.22.6.675

- Received on Jun 28, 2021

- Revised on Sep 8, 2021

- Accepted on Sep 11, 2021

Services

Services

- Abstract

introduction

experimental

results and discussion

conclusions

- Acknowledgements

- References

- Full Text PDF

Shared

Correspondence to

Correspondence to

- Cuijin Pei

-

School of Science, Xi’an University of Posts and Telecommunications, Xi’an 710121, China

Tel : +86 29 88166089 Fax: +86 29 88166333 - E-mail: pcj0125@163.com

Copyright 2019 International Orgranization for Ceramic Processing. All rights reserved.

Copyright 2019 International Orgranization for Ceramic Processing. All rights reserved.